How AI could power the climate breakthrough the world needs

Tomato growers in central India have been increasingly worried about the volatility that extreme weather events have brought to the region. For much of the area, the last decade has been punctuated by severe droughts that led to significant crop loss, impacting the livelihoods of local farmers.

On the other side of the world, Silicon Valley startup ClimateAi is developing an artificial intelligence platform to evaluate how vulnerable crops are to warming temperatures over the next two decades. The tool uses data on the climate, water and soil of a particular location to measure how viable the landscape will be for growing in the coming years.

This is what actually happens at the COP climate summits

The UN has been holding annual climate conferences for 28 years. Here’s a peek behind the curtain.

When the United Nations held its first annual climate conference in 1995 in Berlin, Michael Jordan was still in the NBA, Google didn’t exist yet, and cellphones were rare. Times have changed. But 28 years—and 28 conferences later—we’re still not moving quickly enough to deal with climate change.

This week, tens of thousands of people will attend the 28th “COP,” or Conference of Parties, in Dubai. You might be wondering how much these summits actually accomplish. Here’s a short guide to the process.

Continue reading on Fast Company.

Fund for Climate Solutions awards five new grants

From floods to fire, the 2023 summer cohort of FCS projects seeks scalable climate solutions

The second round of 2023 Fund for Climate Solutions (FCS) awardees has been announced. The FCS advances innovative, solutions-oriented climate science through a competitive, internal, and cross-disciplinary funding process. Generous donor support has enabled us to raise more than $10 million towards the FCS, funding 58 research grants since the campaign’s launch in 2018. This latest cohort of grantees includes five projects working toward a range of scalable solutions to address climate impacts around the globe, from boreal and tropical forests, to heat-impacted cities, to much-discussed and still-struggling carbon markets.

Boreal fire management to protect permafrost and carbon

Lead PI: Brendan Rogers

Co-PI: Peter Frumhoff

As the climate changes, wildfires in boreal forests are intensifying and putting tremendous amounts of carbon at risk of accelerated release from trees and soils to the atmosphere. Motivated by previous Woodwell Climate research, the US Fish and Wildlife Service has recently set aside 1.6 million acres of the Yukon Flats National Wildlife Reserve in Alaska for enhanced fire management to protect carbon and permafrost, and has invited our collaboration to assess the potential and cost-effectiveness of boreal fire management as a to-date overlooked natural climate solution. This invitation is an unprecedented opportunity for actionable scientific research and timely policy impact. Supported by the FCS, the team will conduct the first-ever field study of boreal fire management for climate mitigation. Then, they will bring this work and its implications to decision makers and interest holders in Alaska and DC, positioning Woodwell Climate to expand the reach of this work within Alaska and, ultimately, to other boreal nations.

How climate change will exacerbate the vulnerability of people experiencing homelessness in Las Vegas

Lead PI: Christopher Schwalm

Climate change is exacerbating the vulnerability of people experiencing homelessness in Las Vegas, NV as they face increasing extreme heat risk on the street and flood risk inside stormwater infrastructure. In the city, people experiencing homelessness cope with extreme heat by sheltering in stormwater infrastructure. During the summer of 2022, Las Vegas experienced its wettest monsoon season in over 10 years, resulting in the loss of two lives due to flooded tunnels. This award will support our partnership with local homelessness organizations to develop ways to measure projected lethal heat days and extreme flooding, informing emergency evacuations and raising awareness of climate risk. Research Assistant Monica Caparas will be the on-site scientific lead, and serve as the point of contact for all local partnerships. Because the threat of climate change to people experiencing homelessness isn’t limited to Las Vegas, this work aims to advance climate justice by creating a replicable framework and best practices for establishing and nourishing working relationships with local communities, social service organizations, and government agencies.

Insights and lessons from 20 years of research on forest dynamics and agricultural sustainability in the Amazon

Lead PI: Ludmila Rattis

Co PIs: Marcia Macedo, Michael Coe, Linda Deegan, Christopher Neill, and Paulo Brando

Tanguro Field Station celebrates its 20th anniversary in 2024. Since its establishment by the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM Amazônia), 177 research papers have been published based on work conducted there. More than 215 students and journalists have participated in activities at Tanguro and produced theses, dissertations, policy briefs, and special content in prestigious journals and news outlets. While research at Tanguro has significantly advanced our understanding of tropical regions and continues to provide valuable ecological insights, there is a pressing need to synthesize past research. This award will support the preparation and publication of a synthesis paper that consolidates the findings and key insights from 20 years of research at Tanguro to facilitate a better understanding of the complex interdependencies within tropical ecosystems. This synthesis will also aid in developing a proposal to establish a Biological Integration Institute (BII-NSF) at Tanguro to promote collaboration, interdisciplinary approaches, and knowledge sharing among researchers, policymakers, and people affected by climate change and deforestation in the region.

Detecting post-fire recruitment failure and permanent forest loss

Lead PI: Arden Burrell

Co PIs: Yili Yang, Anna Talucci, and Brendan Rogers

Extensive field campaigns in the boreal forest and the western US have revealed that at an increasing number of study sites, tree species are failing to re-establish after fire destroys the stand. Such post-fire recruitment failure is increasing due to climate change, leading to a loss of both wildlife habitat and carbon storage, and reducing the area’s ability to provide ecosystem services. However, the large-scale extent of recruitment failure has not been studied—this is a key knowledge gap. The goal of this research is to perform a pilot study on existing sites in Yellowstone National Park to prove the feasibility of using remote sensing to detect recruitment failure, with the ultimate goal of obtaining further funding from US government agencies or private foundations. Bringing together Woodwell Climate scientists currently working on separate projects, including Permafrost Pathways, NASA ABoVE, and NSF Arctic System Science programs, this project will build on and synergize their existing research.

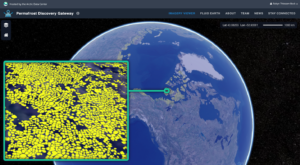

Advancing access to and applications of the Landscape Capital Index

Lead PI: Wayne Walker

Co-PIs: Seth Gorelik, Glenn Bush

Carbon markets could be a powerful mechanism for incentivizing natural climate solutions (NCS) while at the same time enhancing the well-being of land stewards and their communities. However, these markets have faced intense criticism for a lack of transparency and integrity. The project team has been working to develop the Landscape Capital Index (LCI), an independent, data-driven tool for assessing the potential of any tract of land to deliver climate mitigation, co-benefit, and conservation outcomes. With support from the FCS, the team will develop a web-based data platform prototype for beta testing and development into an interactive solution. This future state-of-the-art platform will enable access to and engagement with the LCI. The project team will also conduct targeted validation research to make sure the LCI performs well for strategic use cases in key geographic areas, with the goal of building user confidence in the data product’s integrity.

Can soil carbon credits benefit farmers and help the climate?

Generating soil carbon credits depends on digitalising agriculture and harvesting data from farmers. As Earthshot winner Boomitra prepares to sell its first credits, Energy Monitor investigates who stands to reap the benefits.

Dalip Ram, a rice farmer in the north Indian state of Haryana, inspects an app on his smart phone showing a satellite map of his farm. This app is the product of a San Francisco-based tech company called Boomitra that uses data about the farmer’s land to calculate how much carbon he is managing to lock into the soil of his small plot in order to generate carbon credits. Boomitra just won the Earthshot Prize – which seeks out “the most innovative solutions to the world’s top environmental challenges” – in the ‘Fix Our Climate’ category.

Here’s what upcoming winter may have in store for Massachusetts, New England

On the heels of one of the warmest winters on record last year, StormTeam 5 went to three experts in the field of long-range weather forecasting to get their take on what winter in Massachusetts and New England will be like this year.

All three cited signals that indicate a highly variable season is ahead.

What will 1.5° of warming look like?

Scientists say we’re on track to cross this climate milestone in the coming decade. Listener Julian wants to know what life will look like on the other side of that threshold.

Listen on BBC’s Crowd Science.

Will warm oceans lead to ‘weird’ weather patterns this winter?

Dr. Jennifer Francis of the Woodwell Climate Research Center joined FOX Weather on Thursday morning and explained why all bets are off when it comes to the predictability of what type of weather patterns we can expect this winter.

Alaska’s snow crabs suddenly vanished. Will history repeat itself as waters warm?

ABOARD THE FISHING VESSEL INSATIABLE – Garrett Kavanaugh grabs a fistful of freshly cooked crab and stuffs it into his mouth, a giant smile on his face, as his feet brace against the rolling sea beneath the deck of his boat.

“Oh yeah,” he says. “That’s what it’s all about.”

As the deck of his 58-foot-long boat rolls on the swells of the Gulf of Alaska, Kavanaugh, 24, cracks another crab leg between his tattooed fingers.