NASA Earth Science Division provides key data

In May, the US Administration proposed budget cuts to NASA, including a more than 50% decrease in funding for the agency’s Earth Science Division (ESD) (1), the mission of which is to gather knowledge about Earth through space-based observation and other tools (2). The budget cuts proposed for ESD would cancel crucial satellites that observe Earth and its atmosphere, gut US science and engineering expertise, and potentially lead to the closure of NASA research centers. As former members of the recently dissolved (3) NASA Earth Science Advisory Committee, and all-volunteer, independent body chartered to advise ESD (4), we warn that these actions would come at a profound cost to US society and scientific leadership.

The science behind Texas’ catastrophic floods

At least 95 people died in the flash floods. The disaster has the fingerprints of climate change all over it.

Brazil wants to scale up regenerative tropical agriculture model (Portuguese)

Model developed by Brazilian entities was presented at a conference in Germany preceding COP30

Brazilian researchers presented this Saturday (21/6), in a parallel event to the Bonn Conference in Germany , a new sustainable model for the development of regenerative tropical agriculture. The initiative is led by the Dom Cabral Foundation, but brings together private companies and civil society entities as partners.

The business model designed to accelerate the transition from traditional systems to regenerative agriculture in the planet’s tropical belt includes pillars such as production diversification, soil health, use of biological inputs and a focus on the socioeconomic development of producers.

Between land and water: Tribal relocation and resistance

Climate change is altering the land we live on, and Indigenous communities are on the frontline. In this episode, we bring you to Alaska, where rapid permafrost thaw is threatening the Native village of Nunapitchuk. Then, we head to Louisiana, where the Pointe-Au-Chien Indian Tribe is watching their land disappear underwater due to sea level rise. These threats are forcing these tribes to make the difficult decision: to stay and adapt, or to leave their ancestral home.

Read more or listen on Sea Change.

Woodwell Climate Conversations: Enduring Impact

Max Holmes, President and CEO of Woodwell Climate, and Dr. John Holdren, Former Chief Science and Technology Advisor to President Obama, on adapting with purpose and the lessons learned from political turbulence.

Learn more about our Climate Conversations series.

Climate futures: What’s ahead for our world beyond 1.5°C of warming?

Humanity stands at a critical juncture in the climate emergency: As countries worldwide prepare to submit their climate commitments for the next decade, scientists report mounting evidence that we are very close to breaching the 1.5° Celsius limit set by the Paris Agreement 10 years ago.

Beyond 1.5°C (2.7° Fahrenheit), we increasingly risk crossing climate tipping points, with dire consequences.

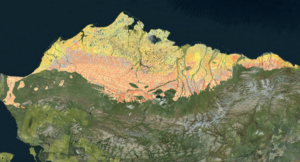

June 2025 collaborator highlight: Permafrost Discovery Gateway

The Permafrost Discovery Gateway (PDG) is an online data visualization platform hosted by the Arctic Data Center that provides openly accessible permafrost conditions across the Arctic region for researchers, educators, and the public. The PDG leverages satellite imagery and artificial intelligence (AI) to create maps of lake change, retrogressive thaw slumps, wildfire areas, ice-wedge polygons, coastal erosion, infrastructure, and surface water. To help communities, researchers, and policymakers navigate the changing landscape, the team aims to provide automated monthly monitoring of permafrost thaw during the snow-free season.

Read more on the Arctic Data Center website.

Gold mining causes long-lasting damage in the Amazon rainforest

A recent study has found that efforts to restore forests in the Peruvian Amazon after gold mining are failing – not only because of toxic soil, but because the land has lost its water.

A popular method called suction mining reshapes the landscape so dramatically that it strips away moisture and traps heat, creating extreme conditions that young trees cannot survive.

The study was led by Abra Atwood of the Woodwell Climate Research Center, alongside collaborators from Columbia University, Arizona State University, and Peru’s Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco.