By Spencer Glendon –

WHRC Senior Fellow–

Spencer Glendon addresses a group of WHRC guests in Boston’s financial district in November 2018.

When I was in graduate school, John Kenneth Galbraith gave a talk. Galbraith was a Professor Emeritus in the Economics Department, but in the crowded audience of curious people, I was the only person from the Economics Department. By this time Galbraith was considered both a has-been and “not really an economist” by mainstream economists. It was the mid-1990s and empiricism and mathematics were essential. Galbraith’s work hadn’t been mathematically complex or rigorous; he had sometimes advocated unorthodox policies including price controls; and he had worked in government during both the Depression and WWII and later was Ambassador to India. He had written mostly for the public and had undoubtedly been wrong about some things along the way. I didn’t know what I would learn at the talk, but I did know that he had always been kind to students and had a long life’s worth of experience. Plus it was free.

His first five minutes were as vivid and astute an observation as I have ever heard, and they perfectly explained the state of economic conversations about climate change.

Galbraith moved to the podium and asked the audience to imagine a history book. He held up his long-fingered right hand as if holding a thick volume by its spine. “Think about the sections of a history book,” he said, running his left hand across the pages of the closed, imagined book. “Note that there are long, uneventful stretches of time that take up very few pages, while thick sections focus on very brief periods of time.” It was the long, uneventful stretches, he went on to argue, that modern economics sought to explain. This advanced discipline was an exercise in explaining the smooth years and offered no advance warning or guidance for the times when the really important stuff happened.

Unknown to me at the time, 133 miles to the southwest of that room in Harvard Yard, an economist named William Nordhaus was in his office at Yale, working on models of how the economy would react to climate change. These models used rigorous data and modeling. They produced precise estimates. They were not written for the public but for academics and government. Nordhaus produced clear, smooth charts of the future as his models took all of the messiness out of this important topic. His papers clarified what Nordhaus described as the crucial choice of climate change: how much to pay for it. Over and over again, his answer was essentially, “not much because climate change isn’t really a big deal.” Here is the final paragraph his 1992 paper “Rolling the ‘Dice’: An Optimal Transition Path for Controlling Greenhouse Gases”:

Even though there are differences among the cases studied here, the overall economic growth projected over the coming years swamps the projected impacts of climate change or of the policies to offset climate change. In these scenarios, future generations are likely to be worse off as a result of climate change, but they are still likely to be much better off than current generations. In looking at this graph, I was reminded of Tom Schelling’s remark a few years ago that the difference between a climate change and no-climate-change scenario would be thinner than the line drawn by a number 2 pencil to draw the curves. Thanks to the improved resolution of computer graphics, we can barely spot the difference!

This fall William Nordhaus was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics for his work. I don’t know if or how Galbraith will be remembered by posterity, but I have little doubt that Nordhaus will be studied for a long time to come, and that such study will find his work—and that of his climate economics collaborator, Thomas Schelling—to have been a leading cause of the dramatic, painful time that is approaching as our long, boring, not-much-happening-here period of economics comes to an end at the hands of climate change. The difference between the climate change scenario and the no-climate-change scenario will be much wider than a line drawn by a number 2 pencil.

Woodwell Climate Research Center and the Nordhaus family have an oddly bookended relationship. In his 1975 paper, “Can We Control Carbon Dioxide?” Nordhaus cites George Woodwell’s work on land biomass extensively. This is the paper that many people cite as the first to introduce the “limit” or “target” of 2°C. In that paper Nordhaus offers different scenarios and comes to what he calls the surprising conclusion that there is no payoff to doing anything about carbon emissions until society approaches a doubling of CO2 from pre-industrial levels, or somewhere around 2020.

By the time George Woodwell gave his testimony to the US Senate Committee on Energy and Resources in June of 1988, he was the Director of the Woods Hole Research Center, whose purpose was to take the insights of science beyond academia so that society could coordinate to stabilize the climate. His testimony offered 11 points of scientific consensus. This testimony could be delivered again today with barely an edit. The concepts have all held true, and the forecasts have been accurate. Points 2 and 11 are worth repeating verbatim:

2. The warming marks the transition from a period of stable climates to climatic instability. Stable or very slowly changing climates have prevailed during the development of civilization.

11. The changes in climate anticipated over the next decades extend beyond the limits of experience and beyond the limits of accurate prediction.

Woodwell was warning that models that were based on our recent, stable past and that could only predict gradual, smooth change were not going to work well. What did the economists do with scientists’ warning?

In the early 1970s Schelling was already famous for his simple, elegant models that helped frame difficult questions of strategy and conflict, especially in relation to nuclear arms. His slim volume, Micromotives and Macrobehaviors, is one of my favorite books. Having been good at thinking about one existential problem that hadn’t turned out badly, he was a popular choice to work on climate change as the science came into existence. Schelling, however, wasn’t a data person. That work was done by his friend William Nordhaus.

Graph illustrating Nordhaus’ predicted consumption in the four cases outlined in his 1992 paper Rolling the ‘Dice’: An Optimal Transition Path for Controlling Greenhouse Gases. (1)Optimal economic policies to slow climate change; (2)20% cut in CFC and CO2 emissions from 1990 levels; (3)No policies to slow or reverse climate change; (4)Geoengineering of technology to provide costless reduction of climate change.

Nordhaus’s non-climate work had highlighted the power of human innovation in development (he is perhaps best known for his work on the decreasing cost of artificial light over time). Together Schelling and Nordhaus made a number of speculative pronouncements that wound up being the central arguments for inaction.

Schelling, in his own summary of the issue decades later in The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics says:

The models of global warming project only gradual changes. Climates will “migrate” slowly. The climate of Kansas may become like Oklahoma’s, but not like that of Oregon or Massachusetts. But a caveat is in order: the models probably cannot project discontinuities because nothing goes into them that will produce drastic change. There may be phenomena that could produce drastic changes, but they are not known with enough confidence to introduce into the models.

This is perhaps the greatest weakness of the economics of climate change. The economists knew from scientists like Woodwell that climate models predicted average outcomes, not a wide range, let alone such a range’s probabilities, even though a wide range of outcomes was possible. They knew that the models were estimated from a period with a docile climate and thus couldn’t foresee extreme outcomes. Additionally, the economists used estimates of economic activity from the short history of industrialized economies, especially post-WWII, during which growth had been smooth and ever-rising. In other words, both the economic and the climate models were calibrated over a single time frame when nothing bad happened. As a result, neither could predict bad, drastic changes. Woodwell warned that this was the essential feature of the problem: really bad things could happen. Schelling and Nordhaus, however, dealt with this problem by shrugging or distracting. Here is Schelling’s next paragraph:

Suppose the kind of climate change expected between now [at the turn of the 21st century] and, say, 2080 had already taken place, since 1900. Ask a seventy-five-year-old farm couple living on the same farm where they were born: would the change in the climate be among the most dramatic changes in either their farming or their lifestyle? The answer most likely would be no. Changes from horses to tractors and from kerosene to electricity would be much more important.

This little thought experiment is a clever bit of misdirection, but let’s go with it. Since so much of America’s most valuable produce is grown in California, let’s consider asking a hypothetical farmer there for the most dramatic changes in life given what scientists can tell us is likely by 2080. A foreseeable answer might go something like this: “Well, we began farming here because the steady snowmelt from the Sierra Nevadas provided perfect irrigation, but since the winters got shorter, the rains more intense, the droughts longer, and the mountain tops ice-free, we dug one well after another for irrigation, but that’s running out too. We have had to deal with one crisis after another, so insurance is sky high. We have a pretty big mortgage, but with collapsing property values, we can’t sell and are likely to declare bankruptcy. Oh, we also have tractors and electricity now.”

But even if farmers and farming suffer dramatically, Schelling and Nordhaus’s models don’t care. They measure dollars of output, and agriculture had become cheap during the boring decades. Schelling continues:

Today, little of our gross domestic product is produced outdoors, and therefore, little is susceptible to climate. Agriculture and forestry are less than 3 percent of total output, and little else is much affected. Even if agricultural productivity declined by a third over the next half-century, the per capita GNP we might have achieved by 2050 we would still achieve in 2051.

Even if the climate severely damages crops, we will not notice the difference, just wait a year. But surely there must be other arguments for doing something. Schelling has answers for all of them.

[An] argument is that our natural environment may be severely damaged. This is the crux of the political debate over the greenhouse effect, but it is an issue that no one really understands. It is difficult to know how to value what is at risk, and difficult even to know just what is at risk. The benefits of slowing climate change by some particular amount are even more uncertain.

This is the second essential failure of this work. Schelling and Nordhaus repeatedly say, in a variety of ways, “If we can’t measure it…” and just move on. What I haven’t read in their work is the second half of the implied logic: “then we should assume it is worth exactly zero.” Neither Schelling in his verbal arguments, nor Nordhaus in his precise models ever gives damaging the environment any value. To have any value at all, something must have dollars closely associated with it. I understand why this is a constraint on a model, but the spokespeople for those models should say that the estimates in the model are biased to be low because of what we know they leave out. For example, knowledge that we might leave future generations a hot, unstable world is worth exactly zero in the models, but that truth has a psychological cost that will rise.

A third argument is that the conclusion I reported earlier—that climates will change slowly and not much—may be wrong. The models do not produce surprises. The possibility has to be considered that some atmospheric or oceanic circulatory systems may flip to alternative equilibria, producing regional changes that are sudden and extreme. A currently discussed possibility is in the way oceans behave. If the gulf stream flipped into a new pattern, the climatic consequences might be sudden and severe.

Is 2 percent of GNP forever, to postpone the doubling of carbon in the atmosphere, a big number or a small one? That depends on what the comparison is. A better question—assuming we were prepared to spend 2 percent of GNP to reduce the damage from climate change—is whether we might find better uses for the money.

The answer, every time, is that there must be better uses for the money, because we can’t figure out what reducing the damage would be worth. He offers 2 percent of GNP forever as his straw man, but what about 1 percent? 0.5 percent? If society had started spending any meaningful amount on this problem when Woodwell and others were teaching the policy makers about the future, we would likely be in a very different situation today. Economists advocated for spending close to zero and repeatedly said that waiting wasn’t costly. Zero is what we got. I believe it is difficult to overstate how important Nordhaus and Schelling’s intellectual and computational work has been in shaping society’s response to climate change.

WHRC asked me to write an essay for their magazine and probably didn’t want me to copy and paste from encyclopedias, congressional reports, and academic papers or go over a past about which we can do nothing. Yet I think it’s important to understand what is in the models that most people use, and think about what we can do better, both when using models and when considering who our audience should be. What I will now offer is a clear, economics-grounded critique of Nordhaus and Schelling that we can actually do something about.

The models Nordhaus built, and continues to update, are difficult and complicated. They have many variables, estimates, and equations. Such models are typically very hard to solve without simplifying assumptions. Here are some of the assumptions:

• Most global models aggregate all countries together into one homogenous economy.

• There is no migration between countries.

• Output is measured, not wealth.

• Nature has no inherent value.

• There is literally no possibility of a discontinuity. The models can only produce smooth paths.

• There is no uncertainty. As a result, there are no ranges of outcomes.

• Ever-increasing riches is the baseline assumption. Future generations will be immensely rich in unimagined (but precisely forecast) ways, and anything we do to slow progress now will limit their future incomes.

To some readers this list will be well-known and received with a shrug. To others it will seem outlandish. I have spent time with the history of these and many other models and am unfazed by them. They do something, and that something can be useful when considering some kinds of questions, but not many. (Indeed, by the 1990s, most research was moving away from such big models because they weren’t very helpful. Economists focused instead on narrow modeling of narrow problems, often called Applied Microeconomics.) The questions they cannot answer are among the most essential to considering climate change. Here are a few key questions Nordhaus doesn’t and Schelling didn’t answer (Schelling died in 2016 at age 95):

How should we value the non-trivial and rising probability that very big, very bad changes happen? If we assign a 10% chance to billions of people starving and wars in virtually every part of the globe over scarce resources, shouldn’t we be willing to pay a high price now? If you were told that you had a choice to play Russian Roulette with our hospitable planet, would you fuss over exactly how many chambers the gun had? The models say that a gun with one bullet is the same as a gun with none because the most likely outcome in both cases is survival.

Under what circumstances do we think that massive migration might be triggered? Schelling, who often sees the world as a negotiation, says it’s hard to imagine rich countries actually caring enough about the poor, tropical, and desert countries to do anything. Plus, other economic models predict that rich countries will be even better off because of climate change since places like Scandinavia and New England will be warmer. Residents of hot places are likely to suffer, but in all economic models the unfortunate sit there and take it. Is that realistic? If not, what price should we assign to preventing mass migration? Will Sweden really have a 29% boost to GDP from warmer weather when tens or hundreds of millions of migrants are coming from the Middle East and Africa?

What about Florida, Arizona, and Texas? Tens of millions of people live in these states, and many of them left places like Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota to have a more pleasant climate. Will the climate make hot, wet, southern places unlivable, and perhaps uninsurable? When will banks stop offering 30-year mortgages in coastal properties? Will the owners of those homes be compensated? If they are owed compensation, who should pay it? People who did not move to risky climates?

Note that the people moving north (or into South Africa, the only temperate country in Africa) will not be “refugees” but “migrants” as they will be looking for a new place to live. Schelling casually argues in a number of places that whole societies have moved or been nomadic before, so that’s nothing new. I have bad news for people who find solace in such lazy economic thinking. Economic history tells us unambiguously that lasting wealth only happens through investment in institutions, people, and structures, all of which depend on big groups of people staying in place and sharing long periods of stability, good civic norms, and clear, well-enforced property rights. Nomads had only the wealth they could carry and did not have smooth, rising incomes. Nomads have neither libraries nor laboratories. They lived in small numbers in vast areas with few other people. As Woodwell noted in 1988, civilization was built on stable climates.

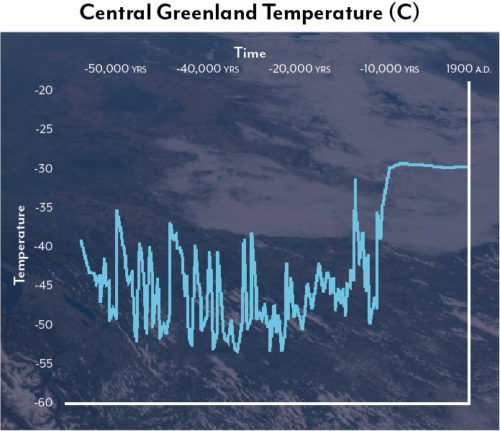

A stable climate allows humans to multiply and settle. The record over time of Greenland’s ice core temperature fluctuation and stabilization is indicative of the gobal stabilization of temperatures within the last 10,000 years. // data: Alley, R.B. 2004. GISP2 Ice Core Temperature and Accumulation Data. IGBP PAGES/World Data Center for Paleoclimatology Data Contribution Series #2004-013. NOAA/NGDC Paleoclimatology Program, Boulder CO, USA.

Is a nice day really worthless? Not long ago I went to see a former classmate who is now a well-known professor of economics at MIT. I told him that I was dedicating myself to climate change. “Why?” he asked, truly puzzled. I told him I had started working on it and found the topic fascinating, beautiful, tractable, and absolutely urgent. “Why aren’t you interested?” I asked him. He said that it didn’t seem like a big deal, some things might get better, others would get worse, that the science had a lot of uncertainty… I then asked him if he didn’t worry about leaving an unhealthy, dangerous planet to his children. His answer should make Nordhaus proud, “We are leaving them the entire stock of human knowledge. It’s a gift they didn’t do anything for. So what if we leave them a bit less of something else like climate?”

This is an essential component of economic arguments: all forms of consumption and wealth are fungible. Any loss in one part of life can be compensated for in other parts of life. And since Nordhaus’s models tell us that economic processes will make people in the future fabulously rich beyond our wildest dreams, any deterioration in the climate will be easy to compensate for. It will simply be a number 2 pencil’s width away since it’s actually almost worthless.

I have a strong suspicion this is untrue, that when told that their children will only recreate indoors, parents will care. When told that their parents are leaving them the entire stock of human knowledge to enjoy indoors but a hot, unstable climate with the attendant unease and political risks, the children won’t see those two things as fungible or compensatory.

Do I have a more precise estimate of the value of the loss of a nice day, or of beauty, or of snow than Nordhaus’s zero? No, but I am sure it is a positive number and, importantly, society has other methods of signaling what’s important besides money. Economists may scoff at this, but non-monetary values like abortion rights, civic freedom, access to health care, and symbols like songs and flags are all worth exactly zero in economic models, yet they inflame spirits and spur action. I have spent several years asking people of all walks of life to describe how they think the world will actually be different in 30 years. None of them has been close. I live in Boston and when I tell them that they should expect temperatures to be over 90(F) for a full month by mid-century, and that if we don’t change the trajectory of carbon emissions, by late in the century almost the entire summer will be over 90 degrees, they are shocked. I am reminded of an ad I saw online last fall. I was doing so much research on Texas that a website I was visiting identified me as being in Austin and being interested in nature. The ad was from an outdoors store and said, “Hey Austin! It’s November, time to go outside again!” I don’t know what form advertising will take in 50 years, but if we don’t change the path of emissions, that ad will be useful in Massachusetts. I can’t imagine what the ads in Texas will say, but there probably won’t be as many customers for them.

Might climate change actually be much more costly in the developed world than elsewhere? This essay is not a referendum on Galbraith vs Nordhaus, but it is interesting to me that Nordhaus’s work is about the smooth flow of history, while Galbraith’s The Great Crash, 1929 is one of the best books about the Great Depression. Financial crisis almost always has two ingredients: high expectations for the future, and a lot of debt. If an entire society assumes the future will be smooth and prosperous, it borrows. If it has sophisticated financiers, it borrows a lot. This is where we are in the developed world: Nordhaus-like models underlie the market’s financial assumptions, including things like municipal bonds for long-lived infrastructure in states like Florida. What will happen when those assumptions are proven too rosy? Will the adjustment be gradual? It hasn’t been in the past.

The above questions are now tractable. Advances in downscaling of climate models allows more accurate assessments of regional and local climates. The variety of available models allows a probabilistic assessment of future local climates. Progress in understanding the likelihood of discontinuous changes can offer us better estimates, even if they are wide and contain a lot of uncertainty.

At the end of my graduate school, I was offered academic jobs but also looked for non-academic ones and, to my advisors’ dismay, took one in an investment firm. After a short time there, I understood the two things I hadn’t liked about academia. First, it divided the world into slivers where experts could work. For example, once Nordhaus claimed climate territory, few economists entered or were visible. Second, academic work is purely about the past. Finance has plenty of flaws, but, like all decision-making fields, it is about the future. The past can sometimes be nailed down precisely, but the future is uncertain. There are no 95% confidence intervals in the future.

I have spent the last 20 years working on the future and thinking about how to approach it. We can do much better than Nordhaus by using probabilities, by disaggregating the world and assessing risks across space, by making vivid the aspects of our probable futures that are hard to value but are not worth zero, and by considering the sad, bad consequences of climate change clearly and openly, both the ones that will be impossible to avoid and the ones that we can avoid if we act. We can share our work with different audiences, including the financial community. Investors assess the future, and if an asset has a 10% risk of catastrophe it is not considered to be identical to an asset with zero risk of catastrophe. In Nordhaus’s models insurance is worthless. In the real world, insurance is bigger than the stock markets and bond markets, but for many people it may not be available before long. I hope this gives you a sense of the work I think I can help WHRC produce. All of it is grounded in science and is in the same spirit with which George Woodwell founded WHRC. It may be a bit more combative and, because we have so much less time to change paths, more urgent, but by trying to find new avenues of influence, perhaps we can offer the future a better range of probable outcomes.

Early in this essay I said that the Nordhaus family and WHRC have an oddly bookended relationship. In May Phil Duffy, who currently holds the same title that George Woodwell did in 1988, also gave testimony on Capitol Hill. Phil was on a three-person panel and did an excellent job helping the Congressional committee understand the urgency and challenges we face. The second member of the panel was a man from a think tank who made one point over and over: yes, it’s happening, but do not heed alarming forecasts as our ever-growing wealth will insulate us from bad outcomes.

The third panelist was Ted Nordhaus, Co-Founder and Executive Director of The Breakthrough Institute, and nephew of William. He also recognized the changes in the climate to come. This was a potentially seminal moment: all of the panelists at a Congressional hearing on climate change agreed about the science. Perhaps they could work together to send a message. It turned out to be impossible. You see, Ted is the author of The Death of Environmentalism and a founder of what he calls eco-modernism or eco-pragmatism. A professional pollster and strategist, he first made a splash by saying that the environmental movement was failing. He and his institute see a need to embrace growth and put our energies into making the world great through building wealth so we can adapt and protect humanity from the coming changes and focusing on developing new sources of clean energy. He sees 2°C as an impossible target and has embraced that: we will have to redefine nature and master it, not be held back by the idea of physical limits. Phil Duffy kept coming back to the need to levy a carbon tax to change the incentives for energy use, a policy even William Nordhaus has promoted since the 1980s. Surely, the panelists could agree on some price. Ted Nordhaus, however, sees any carbon tax as too risky given the riches to come. The market invented the number 2 pencil, surely it can invent much more.

by Dave McGlinchey –

In August 2018, The New York Times Magazine dedicated an entire issue to one article focusing on climate change as an emerging political issue between 1979 and 1989. “Losing Earth” was launched with an event and panel discussion in New York City, featuring author Nathaniel Rich and climate scientist Dr. James Hansen. At the center of the article and the panel, however, was Rafe Pomerance.

In August 2018, The New York Times Magazine dedicated an entire issue to one article focusing on climate change as an emerging political issue between 1979 and 1989. “Losing Earth” was launched with an event and panel discussion in New York City, featuring author Nathaniel Rich and climate scientist Dr. James Hansen. At the center of the article and the panel, however, was Rafe Pomerance.

Pomerance was one of the first people to sound the alarm over climate change on Capitol Hill. He continues his work today as a senior policy fellow at the Woodwell Climate Research Center (formerly Woods Hole Research Center). Woodwell Climate interviewed Rafe about his starring role in the magazine article, and about his career fighting climate change.

Read “Losing Earth” online at: https://nyti.ms/2vwsgAj

WOODWELL CLIMATE: What has the reaction been to the article?

RAFE POMERANCE: A lot of people were surprised by this retrospective. They didn’t know that we knew so much in 1979. They were moved. Otherwise, I have received very positive feedback and congratulations for the good work. Friends and colleagues weighing in, saying it was a good piece.

WOODWELL CLIMATE: As you read it, what do you think were the most important points of the article?

POMERANCE: At the time I began, no one knew anything about the problem. They hadn’t heard of it. There was no

knowledge except for a small corner of the scientific community. We had to educate policymakers who had no familiarity. And the most important point of the article was the failure of these institutions to respond.

The second thing is that [solving] climate change is a big job. We know that we need to shift from a carbon-based economy to a carbon-free economy and that’s the largest task we have ever taken on.

We could have been on our way but you had this disinformation campaign that was designed to seed doubt – to undermine the scientific consensus. That has had a deleterious result. I call it the denialist disease.

WOODWELL CLIMATE: You had numerous conversations with the writer, Nathaniel Rich, to share your story. Tell us about the process of developing this article.

POMERANCE: The conversations took place over a year and a half—something on that order. I didn’t know how the piece was going to shape up. I talked to Nathaniel many, many times. Sometimes about the same conversation or event. He was trying to get the sequence right. And then the way he put it together was excellent.

I was so impressed by his research. We would talk, and he would come back having turned up transcripts and events that I had forgotten about. I didn’t remember every detail, and he would remind me based on a transcript.

He had over 100 interviews. In the end, he did something that hadn’t been done before. He told a story that hadn’t been told.

His depiction of the Charney Committee (a federal research group assembled in 1979 to study carbon dioxide and climate change) meeting in Woods Hole was amazing.

There are two schools of thought about the article. The first is, they are amazed by how much we knew back then. They’re taken in by the story, and they could read the whole thing because Nathaniel is such a good writer.

The second school of thought is that he downplayed the campaign of disinformation. These are critiques around the edges. My dominant feeling was that this piece really generated an enormous amount of attention and interest.

WOODWELL CLIMATE: George Woodwell, who founded Woodwell Climate Research Center (then Woods Hole Research Center), was mentioned several times in the article. Rich wrote that Woodwell “had been calling for major climate policy as early as the mid-1970s, and an international effort coordinated by the United Nations.”

POMERANCE: I was really glad to see that George was mentioned and his insights were included. He played an absolutely crucial role in identifying the role of forests and natural systems in the carbon cycle. He was the voice for that issue.

He was on the second panel in the (1986 Sen. John) Chafee hearing. We fought to get him a spot and he did a great job.

I thought that the article could also have focused more attention on the central role played by Gus Speth—when he was at the White House’s Council for Environmental Quality and at CEQ and the World Resources Institute.

WOODWELL CLIMATE: Looking back, reading the article, and seeing where we are today, do you feel frustrated? Or, was it all worth it?

POMERANCE: Oh, absolutely. Every bit of effort was worth it. I knew very early that this would become a dominating issue on the planet. We started out and nobody knew anything about it and now everyone does. Was it worth it? Absolutely.

WOODWELL CLIMATE: What is the way forward?

POMERANCE: Organizing in states that are being affected by impacts that are clearly attributable to climate change. Like sea level rise. In 2018 we saw a Republican in Florida sponsoring a carbon tax bill.

It requires a massive organizing effort in states based on impact. The question is whether climate change and its impacts can play an important role in purple states. North Carolina. Florida. Texas even. Impacts are showing up. The question is whether these impacts are important enough that they become political issues in campaigns.

WOODWELL CLIMATE: What has changed since you started working on this issue?

POMERANCE: It was clear then—but it’s absolutely clear now— that we have to get this done. We have to decarbonize. I’m more convinced than ever.

It requires a massive response. What the story tells is that then it was a prediction and now we are observing the reality. And the forecasts are only harsher. The challenge is scale, urgency and timing. But we need a global push, and as soon as possible.

A force for Arctic science: Dr. Jennifer Francis joins Woodwell Climate

At the 2016 Arctic Matters Day, hosted by The National Academy of Sciences, Dr. Francis presented on the connection between weather and a melting Arctic

Before Dr. Jennifer Francis was a world-renowned atmospheric scientist. Before she pioneered the idea that a rapidly warming Arctic affects weather at lower latitudes. Before she became the go-to quote for journalists covering extreme weather in the age of climate change. Before she became the newest senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center (formerly Woods Hole Research Center).

Before any of that, Jen Francis sailed to the Arctic.

In the early 1980s, Francis took a break from her undergraduate studies and took five years to sail a 45-foot sloop around the world with her husband.

“As part of that we went up to the Arctic. This was pre-GPS. This was pre-cell phones. It was before you could get good weather information,” Francis said. “We went up to Svalbard (Norway), and the weather information we could find was basically useless.”

The couple sailed from Norway to Iceland, and then planned to continue on to Greenland and down the coast of North America to Massachusetts. When they left Iceland it was mid-September, with 12 hours of daily darkness.

“Immediately we started seeing icebergs, which was unexpected and bad,” Francis said. “Not small icebergs, the size of houses. It had been a really warm, early summer in eastern Greenland. So a lot more ice than normal had broken off of the glaciers. That first night was probably the scariest part of our entire trip.”

They were forced to retreat, turning back to Iceland and eventually re-routing directly south. The detour added 6,000 miles to their trip, but Francis was hooked by the idea of better understanding weather patterns.

Dr. Francis and her husband in the 1980s, navigating through sea ice on the way to their boat.

Back on land, she returned to school at San Jose State University where she earned a bachelors degree in meteorology. She decided that she wanted to focus on research, not forecasting, and got her Ph.D. from the University of Washington.

“I’ve been studying the Arctic my entire career, really starting as an undergrad,” Francis said. “It goes back to when my husband and I sailed up the Arctic in 1984. I knew then what I wanted when I went back to school.”

Now, more than three decades later, her research is focused on unseasonably warm weather and the resulting impacts. The Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the world, and Francis has zeroed in on the connection between that warming, and weather changes in mid-latitudes. The crux of her work is that a warmer Arctic disrupts the flow of air from lower latitudes toward the poles. That disruption, in turn, has disrupted and redirected the jet stream.

She joined Woodwell Climate Research Center from Rutgers University’s Institute of Marine and Coastal Sciences in September to continue this research.

“I feel like we are just scratching the surface of how a rapidly warming Arctic is affecting weather patterns at mid-latitudes. There is a lot more work to do,” Francis said. “That’s really where I plan to focus, with the ultimate goal of knowing what to expect in the future, in the next decade to four decades. That’s really the window where policymakers need to think about decisions they have to make. Decisions about infrastructure. Really expensive decisions that have to be made and they shouldn’t be made in a vacuum. They should be made with good information.”

Three years ago, Francis spoke at a Woodwell Climate public event. And in 2016, she discussed Arctic warming with a panel of Woodwell scientists on the main stage at the annual Arctic Circle conference in Reykjavik. But the news that she was joining the Woodwell Climate staff sent a buzz of excitement through the headquarters building.

“I’m absolutely thrilled to have Jen Francis at [Woodwell Climate],” said Woodwell Deputy Director Dr. Max Holmes. “I’ve greatly admired her for many years. In fact, if I had my choice of any scientist in the world to add to our staff, she’d be the one. She shows how changes in the Arctic are impacting extreme weather outside of the Arctic, including where most of us live.”

Francis’ research has received significant academic attention, but she has also broken out to a wider range of outlets.

“Not only does she do cutting-edge science, but she does a superb job of communicating her research to broad public audiences,” Holmes said.

When historically low temperatures struck the midwest of the United States earlier this year, Francis appeared on PBS’ News Hour to discuss the latest research on climate change and disruptions to the polar vortex, and was interviewed by the New York Times, the Associated Press, USA Today, the Chicago Tribune, and numerous other outlets. In 2018, she authored an op-ed in the Washington Post on the extreme weather phenomenon and was quoted in publications nationwide about record-breaking hurricanes. She has appeared on cable news and National Public Radio, and has spoke to countless audiences.

“There is the communications side that I spend a lot of my time doing, taking these complicated research results and weaving them into story,” Francis said. “I talk to media. With an event like Hurricane Michael or Hurricane Florence I probably talked to six media people every day. I do a lot of writing for more targeted journals. And I’ll talk to just about anybody. I see that as a really important aspect of my job. I didn’t plan on that. I kind of got thrown into it. But I really like it.”