Northern communities adapt to a new era of Arctic-boreal wildfire

Arctic Indigenous Peoples face deepening health crises, displacement, and cultural disruption due to wildfire. Indigenous expertise offers solutions.

A wildfire burns near Denali National Park in Alaska during the summer of 2024.

photo by the National Park Service

Summers in the Arctic-boreal region are becoming increasingly defined by fire. In 2023, Canada endured its worst wildfire season in history, with nearly 200,000 Canadians displaced. Fast forward to summer 2025, and the country faces its second-worst wildfire season on record, with 470 outbreaks deemed “out of control” by August. Siberia and Alaska are also confronting active fire seasons.

For Arctic communities, the physical impacts of smoke exposure, the toll of evacuations and destruction, and the threats to cultural traditions compound the danger of extreme fires. But Indigenous science and cultural traditions offer a path towards justice and resilience.

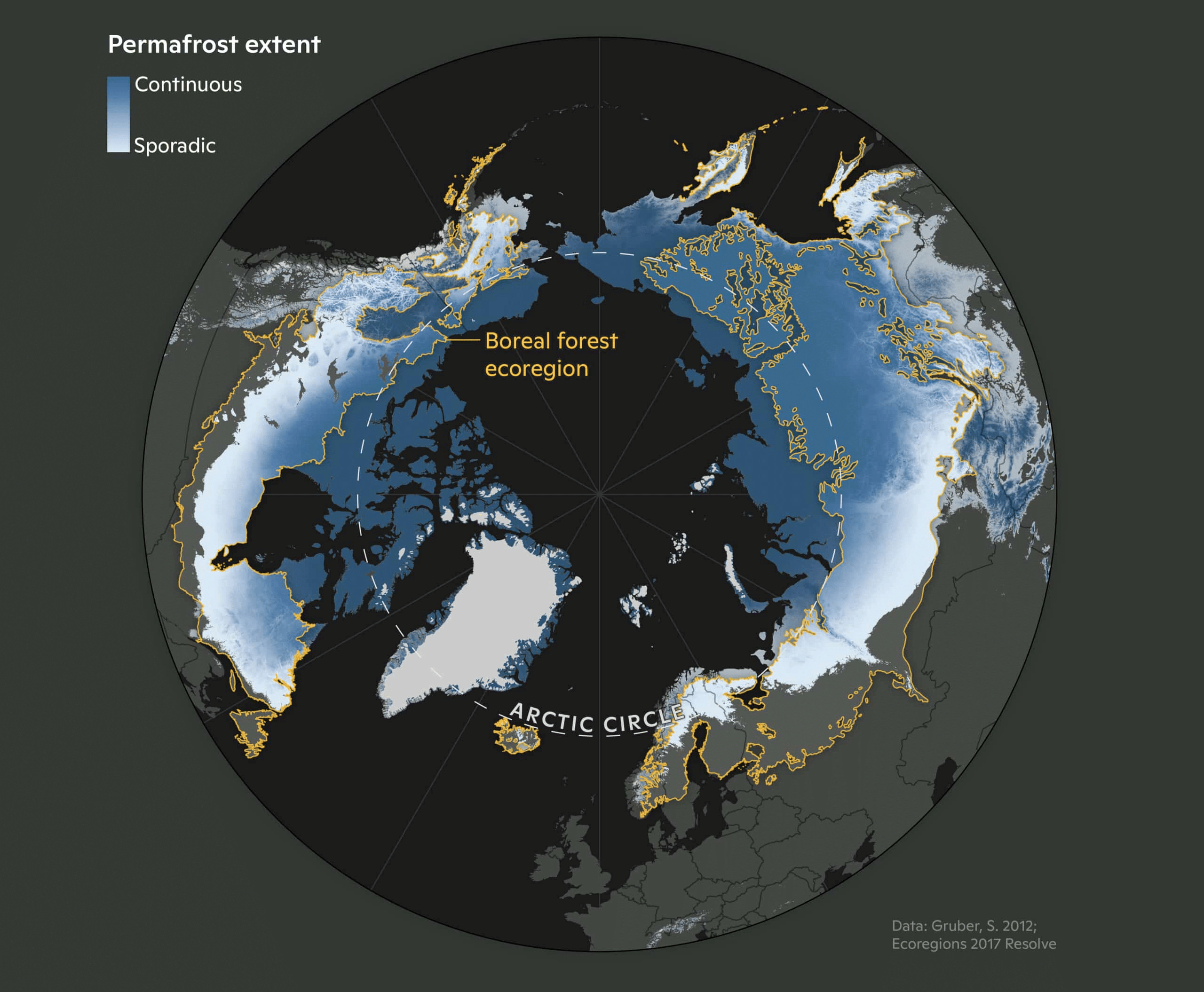

A map illustrating the boreal forest ecoregion and permafrost extent across the circumpolar north.

map by Christina Shintani

Climate change and colonial histories fuel the fire

Climate change has created hotter and drier conditions in the north, increasing the frequency and intensity of Arctic-boreal wildfires. These wildfires amplify global warming, creating a feedback loop by burning deep into permafrost, a carbon-rich soil, and releasing stored carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere. A recent study led by Permafrost Pathways researchers found that wildfire has contributed to the Arctic’s shift from a net absorber to a net emitter of carbon. That increase in emissions in turn fuels even more fires. Between 2003 and 2023, the Arctic-boreal region saw a sevenfold increase in extreme wildfires.

Abrupt permafrost thaw after a wildfire in interior Alaska.

photo by Torre Jorgenson / University of Alaska Fairbanks

“Things have really changed in our traditional territories,” said Woodwell Climate’s Adaptation Specialist, Brooke Woods. Woods is a Tribal member from Rampart, Alaska, and she currently lives in Fairbanks, Alaska. “We had two fires close to Rampart this summer. We’ve had back-to-back fires over the past three summers. Growing up, I don’t ever recall back-to-back wildfires surrounding our communities.”

The increase is also due, in part, to increased lightning strikes, which are occurring more frequently as warming temperatures further destabilize atmospheric conditions, leading to more storms that produce lightning.

“Our summers are drier and we’re having more severe heat events as well as more intense lightning and thunderstorms now, too,” said Woods. “When we had the fire in Rampart, in the midst of this wildfire, one of the storms actually produced 1600 lightning strikes across Alaska.”

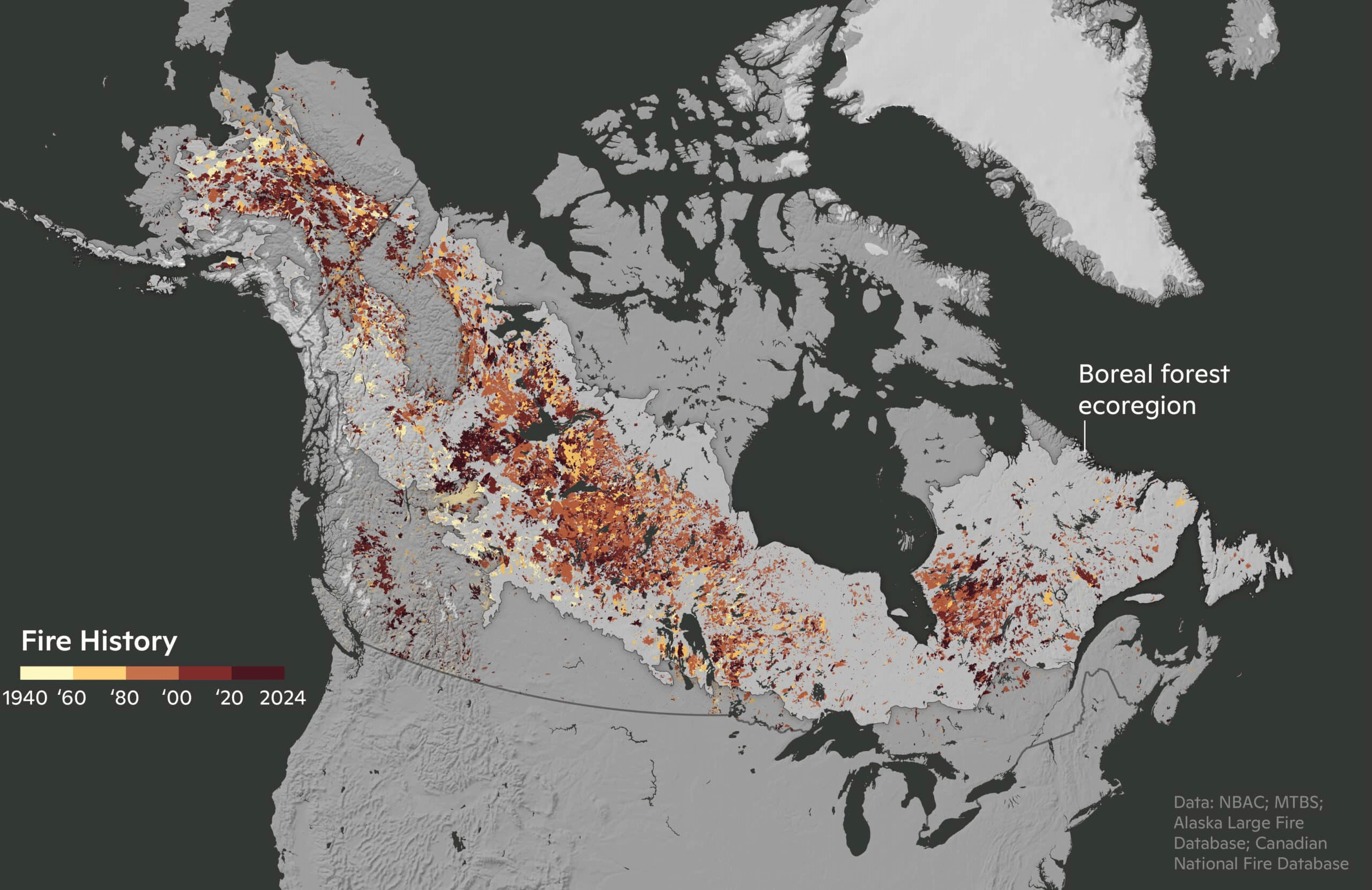

Fire history in the boreal forest ecoregion between 1940 and 2024.

map by Christina Shintani

The history of colonialism in North America has also played a role in today’s extreme wildfire regimes. For millennia, Indigenous Peoples across the Arctic practiced cultural burning—using small, controlled fires to manage the land, reduce dry fuel buildup, and prevent large, catastrophic wildfires. These practices not only protected ecosystems but also supported biodiversity and were deeply rooted in cultural knowledge and tradition. However, colonization disrupted these systems as Indigenous communities were forcibly removed from their lands, and cultural burning was often banned and criminalized altogether.

“Elders risked jail time for burning,” Dr. Amy Cardinal Christianson told Chatelaine Magazine. Christianson is a Métis wildfire expert and Policy Advisor for the Indigenous Leadership Initiative who co-hosts the podcast Good Fire and serves on the board of the International Association of Wildland Fire. “That’s how badly they knew that the land needed to burn.”

This erasure, combined with colonial fire suppression tactics, has led to the accumulation of flammable undergrowth that makes the land more vulnerable to intense and widespread fires.

Fire in Alaska.

photo by Ryan McPherson / Bureau of Land Management Alaska Fire Service

Smoke, displacement, and cultural survival

Increasingly active Arctic-boreal wildfires are not just environmental disasters, they’re also cultural and human crises.

Wildfire smoke—which can contain soot and high levels of mercury— threatens the health of Arctic communities and can put vulnerable groups, like elders, young children, and those with pre-existing health conditions, at prolonged risk well after the fires have gone out.

“In my baby’s first year of life in 2023, we had such bad air quality [in Fairbanks]. It impacted his respiratory system, and it was just so hard for him to be able to nurse,” said Woods. “I was even considering driving 300 miles to the next urban area to get him to clean, healthy air because there was also a fire in Rampart. It impacted our safety in both of the places that we call home.”

The mental toll of wildfires can also be just as devastating as the physical impacts, as communities must navigate evacuation logistics, loss, and displacement with very little governmental support.

“Communities are thinking about how the wildfire crisis is real—it’s driven them from their home and maybe destroyed their home—they’re thinking ‘what else am I going to lose’?” said Edward Alexander, Senior Arctic Lead at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, Chair of Gwich’in Council International, and Co-Chair of the Arctic Council’s Expert Group on Wildland Fire. “Then, becoming unhoused… people lose their jobs, their businesses, or their investments. They lose forward momentum in their life.”

Wildfire near Highway 63 in Alberta, Canada.

photo by Darren R.D.

In addition, evacuation is far more complicated in the Arctic. Many remote communities and villages in Alaska and Canada either have only one main road or aren’t connected to road systems at all, making them accessible only by plane or boat, which presents a logistical and financial challenge for mass evacuation. The combined impacts of smoke, heat, and economic insecurity can also present impossible choices.

“If you look at not only the health disparities but your income, what can you afford to keep yourself healthy?” said Woods. “Can you afford air filters for your home? Can you afford and have access to air conditioners with filters? Because not only are you battling the smoke, but you’re also battling this heat. So just navigating those at different income levels can be very complex.”

Fire doesn’t just destroy infrastructure and threaten health and well-being, it also disrupts Indigenous ways of life, cultural connections to land, intergenerational knowledge sharing, language revitalization, and cultural history tied to specific places like hunting trails, fish camps, and seasonal migration.

“When we were still able to subsistence fish in Alaska, and had wildfires at the same time, there were community members in Rampart that were not able to meet all of their subsistence needs due to wildfires,” Woods said.

A cultural burn in Gwichyaa Zhee, Alaska.

photo by Edward Alexander

Traditional solutions for modern problems: A return to cultural burning

In Good Fire, Christianson discusses ways to restore the modern world’s broken relationship with fire and the need to integrate systems that not only respond appropriately but are also proactive and predicated on Indigenous Knowledge and expertise. This is where cultural burning offers a way forward—a way to view fire not as a threat, but as a critical tool for keeping land healthy and communities safe.

The First Nations Emergency Services Society (FNESS) and the Indigenous Leadership Initiative (ILI) recently released the “Create a Cultural Burn Pathway” workbook to support Indigenous communities in creating cultural burn programs to reduce wildfire risk and maintain healthy connections to the land.

“Fire doesn’t have to be scary,” said Christianson in a video produced by the Indigenous Leadership Initiative. “It doesn’t have to be something we live in fear of every summer. We can have a better relationship with fire that can have really important benefits.”

Traditional burning is a culturally grounded, community-empowered, and ecologically practical approach to managing and mitigating wildfire risk in the North, born from generations of Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Unlike conventional fire suppression, which often seeks to eliminate fire altogether, cultural burning is a proactive, place-based practice rooted in Indigenous governance, values, and ecological understanding. These approaches aren’t about fighting fire—they’re about embracing it to foster sovereignty, revitalize knowledge, and deepen connection to the land.

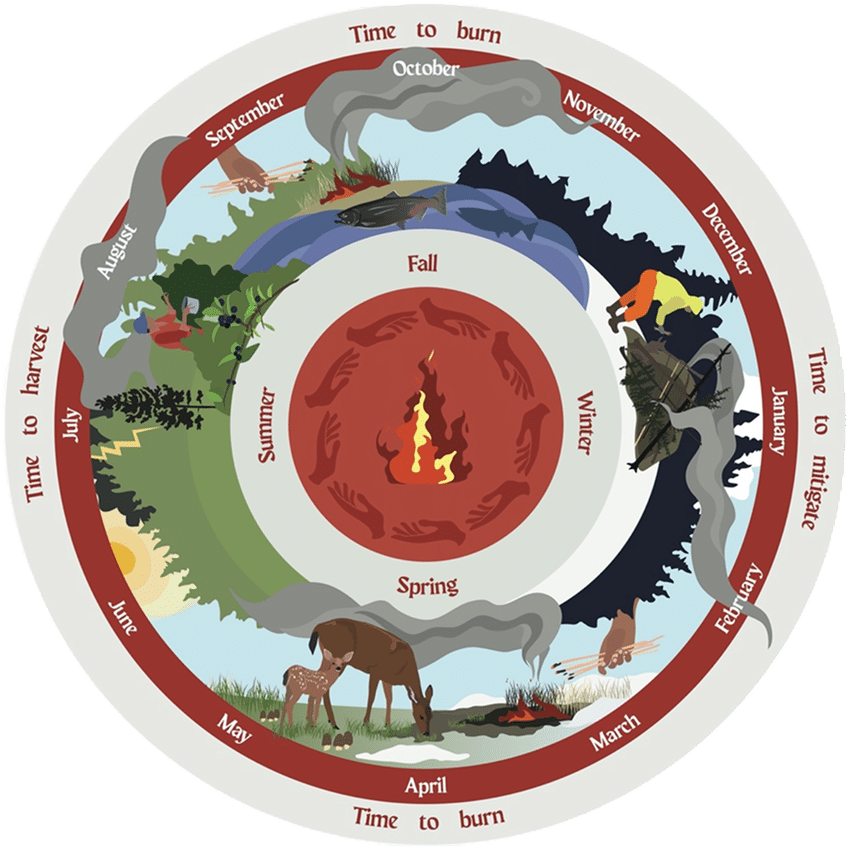

A seasonal calendar of Indigenous fire stewardship from the publication, “The right to burn: barriers and opportunities for Indigenous-led fire stewardship in Canada.”

image concept by K.M. Hoffman and A.C. Christianson, design and illustration by Alexandra Langweider of Align Illustration

Beyond the health of the land and forests, cultural fire also contributes to cultural resilience and maintains Indigenous connections to land and community. Cultural burns ensure practices are guided by traditional protocols and adapted to local ecosystems. Community members, including youth, are involved—passing knowledge between generations and restoring cultural roles that were disrupted by colonization.

Which is why, according to Alexander, placing the emphasis on the health of the forest, ecosystems, and community overall, rather than on controlling fire, should be the real goal.

“We should be thinking a little differently,” Alexander said. “Cultural fire is a tool, but fire is not the emphasis. It’s the health of the forest, it’s the health of the land, it’s the health of the animals and birds, it’s the health of our peoples and communities. That’s the emphasis.”

A cultural burn in Gwichyaa Zhee, Alaska.

photo courtesy of Tim Boese, Silverback Films

From ‘wildfire to mildfire,’ Indigenous fire stewardship as a path forward

Cultural burning is just one part of the solution, which will involve moving away from colonial fire suppression methods altogether and supporting Indigenous-led fire stewardship models with meaningful changes in policy and funding. Woods says she’d like to see Indigenous-led fire programs represented as part of a broader recognition of Indigenous sovereignty in the North.

“I’d like to see more local people leading the work rather than just renting out their equipment or hiring them as boat captains,” Woods said. There are more opportunities for Indigenous People to help their own communities. I feel there’s always time to course correct and really acknowledge and honor the 229 Tribes of Alaska and their practices that have maintained very healthy land and ecosystems for so long.”

In Alaska, Indigenous-led wildfire initiatives—like the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Emergency Firefighter (EFF) program—create opportunities for local members of Alaska Native communities to join crews and integrate their traditional knowledge and expertise of the land to help keep their communities safe. In Canada, Fire Guardian programs—which Dr. Christianson has long been advocating for—aim to get good fire back on the land through Indigenous stewardship and traditional practices.

Bureau of Land Management Alaska Fire Service contract hand crew made up of firefighters from Alaska communities of Tanana, Minto, Nenana, Mountain Village, and Marshall.

photo by Beth Ipsen / Bureau of Land Management Alaska Fire Service

Alexander says he hopes recognizing cultural burning and other forms of Indigenous Knowledge as legitimate science will help prioritize them in land management.

“It’s critically important science that we need to help us manage the wildland fire crisis in the circumpolar north,” said Alexander.

Alexander imagines a future where wildfire becomes mildfire. Where communities in the north are adequately resourced and wildfire management becomes proactive and rooted in Indigenous Knowledge and expertise, while prioritizing and supporting sovereignty.

“Indigenous fire management looks like a vibrant landscape where you don’t have severe wildland fire, but you have increased biodiversity, where the vegetation is more nutritious for the plants and animals, and that permafrost and other hugely important resources are protected,” Alexander said. “I also think that it’s an integral part of respecting the sovereignty of Indigenous Peoples, of respecting the self-determination of Indigenous Peoples to manage our territories how we see fit, and I think that it’s a really critical approach that we need to all be listening to. Our collective future really depends on it.”