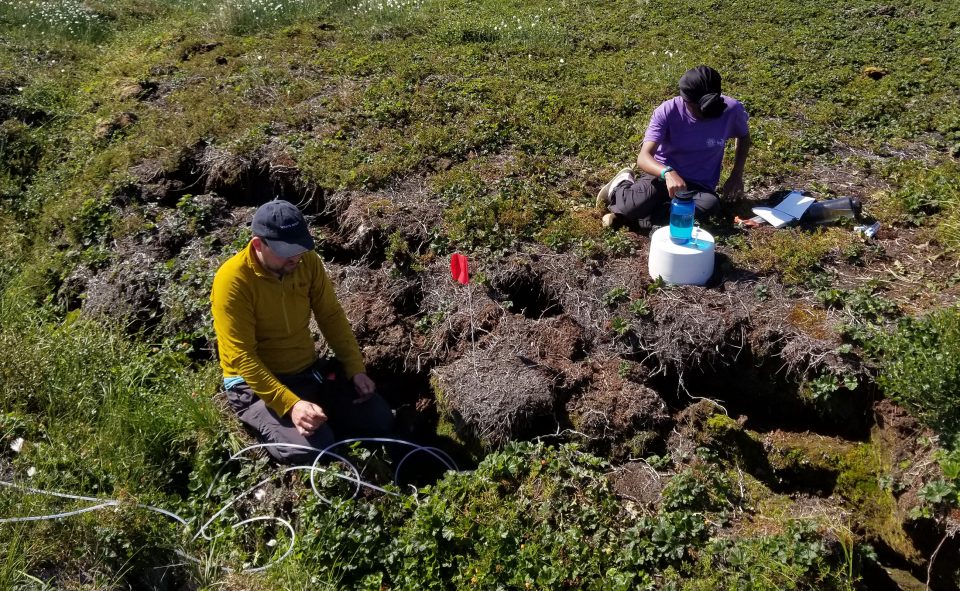

Warning signs on Alaskan tundra

Investigating an area of slumping caused by permafrost thaw.

Photo courtesy of Aqua Sanders

When I look back on this year’s Polaris Project trip to the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge, I’ll remember our incredible student and faculty participants, the world-class science they produced, and the local residents who shared their firsthand experiences with climate change impacts. I’ll also remember some unexpected glimpses into our climate-changed future—extreme heat, strong lightning storms, wildfire smoke, and huge slumps of rapidly thawing permafrost.

Through the Polaris Project, Woodwell Climate Research Center (formerly Woods Hole Research Center) scientists have been bringing students to the Yukon Kuskokwim Delta, investigating the impacts and implications of global climate change, permafrost thaw, and wildfires.

Our journey took us through Anchorage to Bethel, and finally to the campsite, located about 50 miles from Bethel on the Alaskan tundra. The weather was cool and damp at the beginning of the expedition, but it soon turned hot, with temperatures hitting 90°F and continuing Bethel’s record-breaking year. Every month this year has been at least 5°F above the historic average. February was 17.3° above average (breaking the all-time record by 3.3°).

On top of the heat, there was also a lot of smoke from nearby wildfires, which made for very difficult working conditions. We were fortunate the fires stayed clear of camp or we would have had to evacuate.

We saw signs of accelerating permafrost thaw, including massive ground collapse. In areas affected by a 2015 wildfire, thaw depths were a meter or more, which is roughly double what we’ve seen the last couple of years. It’s alarming because globally, permafrost stores more carbon than humans have ever emitted by burning fossil fuels, and that carbon is rapidly thawing, placing it at risk of decomposition and release into the atmosphere.

Just as important as the research we conducted during the trip is what we left behind. Woodwell Research Assistant Sarah Ludwig put up a flux tower that will measure carbon dioxide and methane emissions from tundra, wetlands, and lakes. There’s a critical shortage of emissions data from thawing permafrost and this tower will be one step toward bridging the gap. We recently received funding from the Moore Foundation to install a second tower in an area that burned in 2015 so that we can better understand the long-term consequences of wildfire on permafrost carbon. We’re hoping to secure further funding to put up more towers in additional areas.

Alaska’s permafrost is a critical bellwether. Research shows much of the permafrost could be thawed by the end of the century—if not much sooner. But how much permafrost thaws depends on the choices we make now. If we act to get off of fossil fuels and simultaneously protect and restore natural carbon kept safely in forests and soils, we can avoid the worst harms of climate change. The fate of Alaska—and the world—is in our hands.

Dr. Sue Natali is an Associate Scientist and Arctic Program Director at Woodwell Climate Research Center, and she is Director of the Polaris Project. Read student blog posts detailing this year’s expedition at ThePolarisProject.org.