Amazon Deforestation and Fire Update: December 2020

Escalating fires and widespread dry conditions raise concerns about forest degradation.

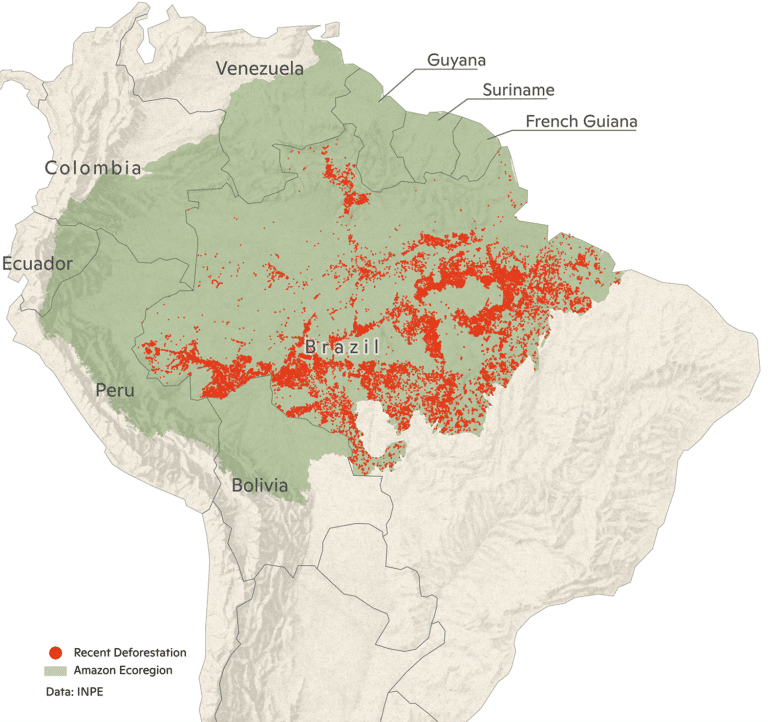

Deforestation and fires in the Brazilian Amazon drew international attention in 2019 as they jumped to their highest level in over a decade. 2020 has been different, but no less extraordinary. November deforestation and fire amounts declined from their record-setting values in October. In total, deforestation during the calendar year of 2020 is somewhat less than 2019’s record extent, but is still above average for the last 15 years. And because it is an exceptionally dry year, fires are now greater than in any year since measurements began in 1998.

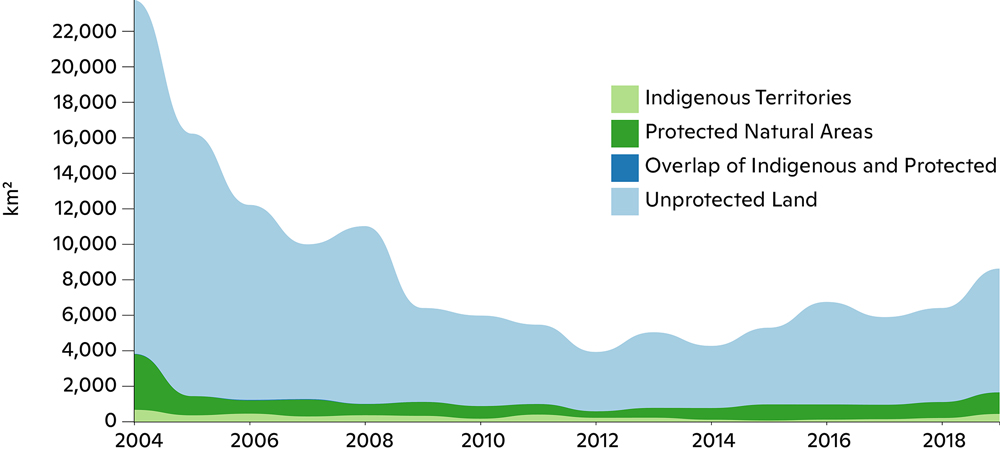

Amazon forests absorb and store roughly a tenth of human carbon dioxide emissions each year, but this critical carbon sink is threatened by deforestation and degradation of forest health. Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon declined by 70% between 2004 and 2014. In recent years, however, deforestation has increased and fires have followed as people burn the trees they’ve recently cut down.

Building on the deforestation and fire data released regularly by Brazilian government scientists, we present an analysis of the carbon footprint of this year’s deforestation as well as where deforestation is happening and an analysis of the current climate conditions—key information for identifying fire risk hotspots and shaping solutions.

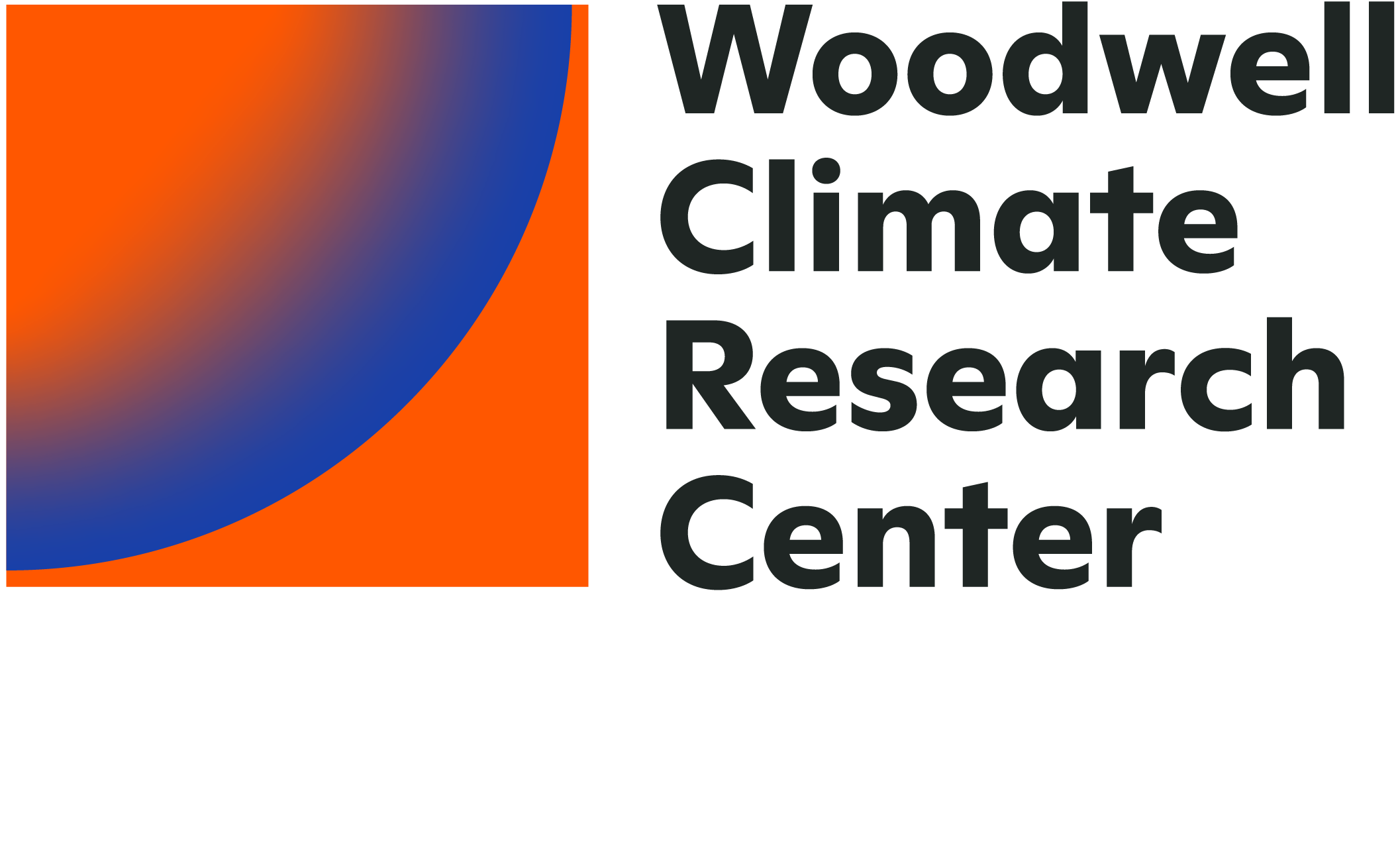

Climate / Drought

2020 has been an extraordinarily dry year throughout most of the Amazon (except in the northeast). It is remarkable because of how little rain has fallen and how much of the Amazon is affected. The southern Amazon saw only 1100 mm of rainfall this year, the least recorded in the entire record dating back to 1981. A normal year sees about 1400 mm of rainfall. Even the far northeastern Amazon, which normally experiences strong rainfall in all months was exceptionally dry this year, nearly tying the driest year recorded in 1992. The dry conditions are likely related to the strong La Niña that has developed in the last few months in the eastern Pacific (which, incidentally, is also related to the record-breaking hurricane season in the Atlantic Ocean this year).

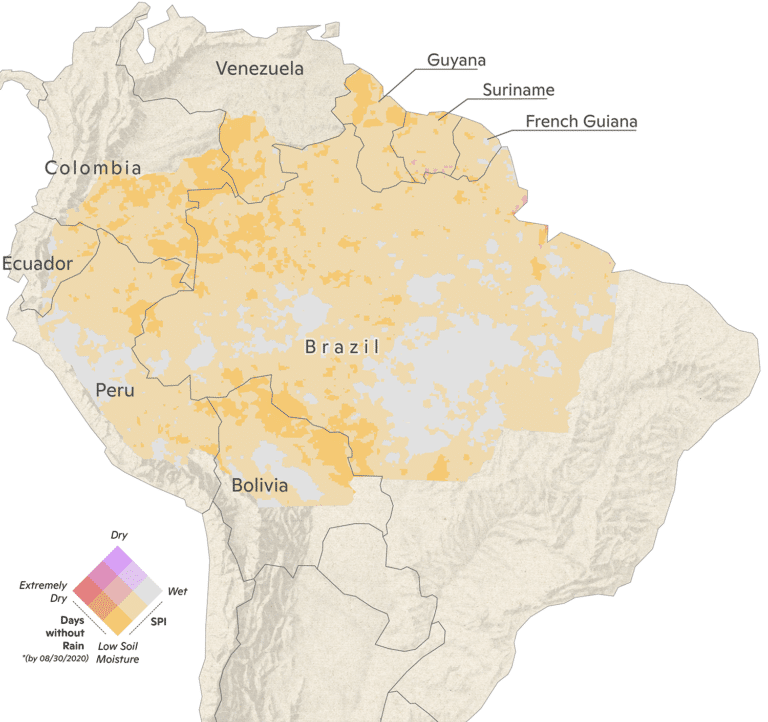

Forest fires are not a naturally occurring phenomenon in the Amazon—they are almost always a result of human activities. When deforestation (red dots) coincides with dry conditions (yellow), fires lit to burn felled trees can escape into neighboring forests, destroying or degrading them.

The red dots represent locations where deforestation has occurred since October 2019. We chose October as the cutoff because most areas that were deforested in this period will be burned this year.

Learn More

Climate conditions are represented by the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI), which characterizes the meteorological drought for a period of 3 months, using monthly precipitation data (CHIRPS daily). At this time scale the index is closely related to soil moisture. It quantifies observed precipitation as a standardized departure from a selected probability distribution function that models the raw precipitation data. The SPI values can be interpreted as the number of standard deviations by which the observed anomaly deviates from the long-term mean. For the operational community, the SPI has been recognized as the standard index that should be available worldwide for quantifying and reporting meteorological drought.

Deforestation

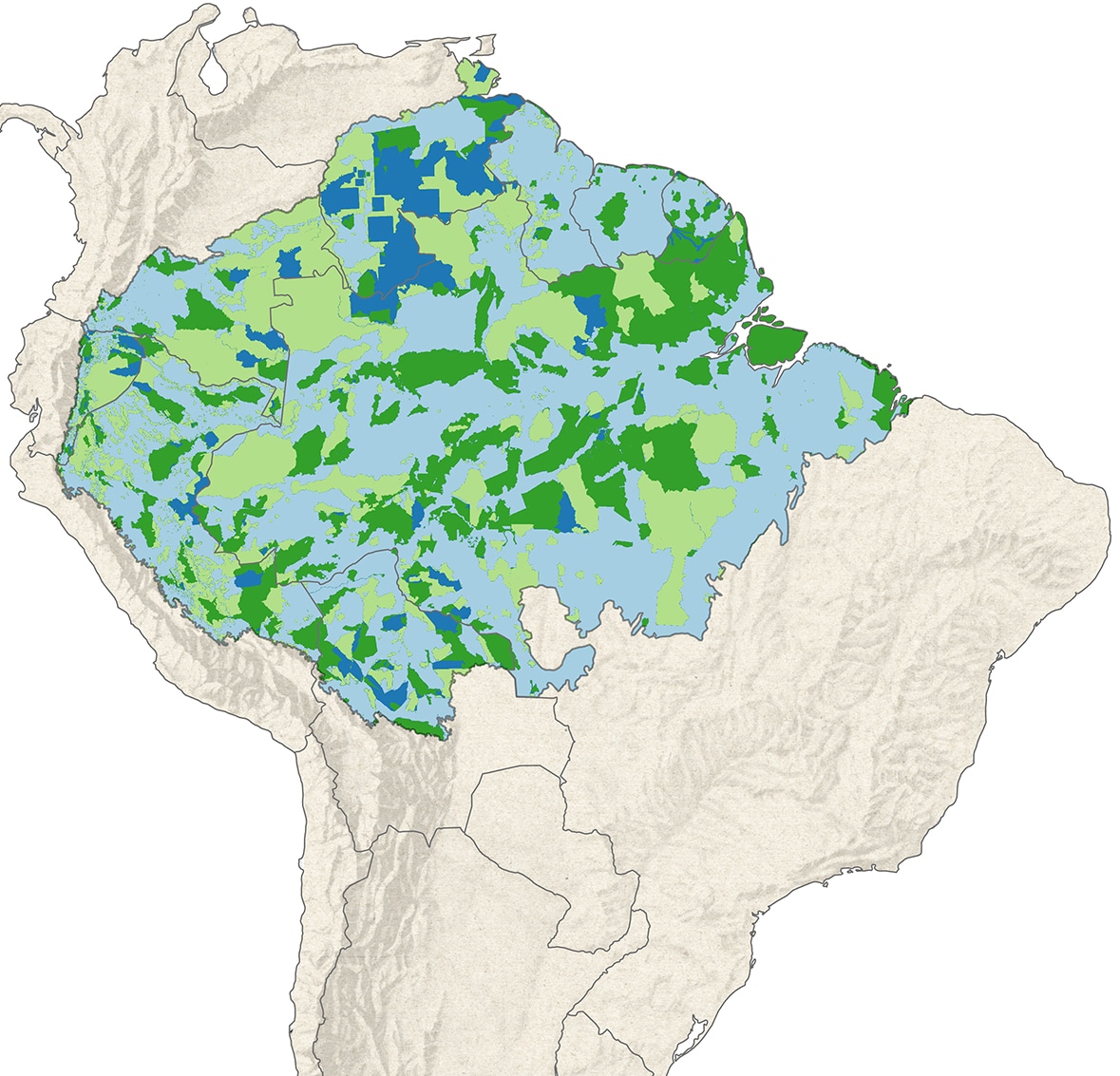

As the year nears an end, 8,905 km2 of forest has been destroyed so far in 2020. This is 15 percent less than the 10,513 km2 that had been deforested by the end of November in 2019. This year, as in previous years, most deforestation has taken place on unprotected lands, including private properties and federal lands without a protected status. However, deforestation in protected natural areas has been rising and accounts for 16% of deforestation to date this year, suggesting a need for greater enforcement of existing designations.

Learn More

Monthly estimates of deforestation in 2019 and 2020 are taken from the Brazilian national space agency Real-Time System for Detection of Deforestation (DETER). DETER estimates are provided each month, but are based on relatively coarse resolution MODIS satellite products. Therefore, values tend to be an underestimate.

Annual deforestation values from 2004-2019 are provided by the Brazilian national space agency Program to Calculate Deforestation in the Amazon (PRODES). The PRODES product is based on 30m resolution Landsat imagery and is therefore a more accurate representation of the total deforestation, but it can only be provided on an annual basis.

Deforestation by Land Tenure

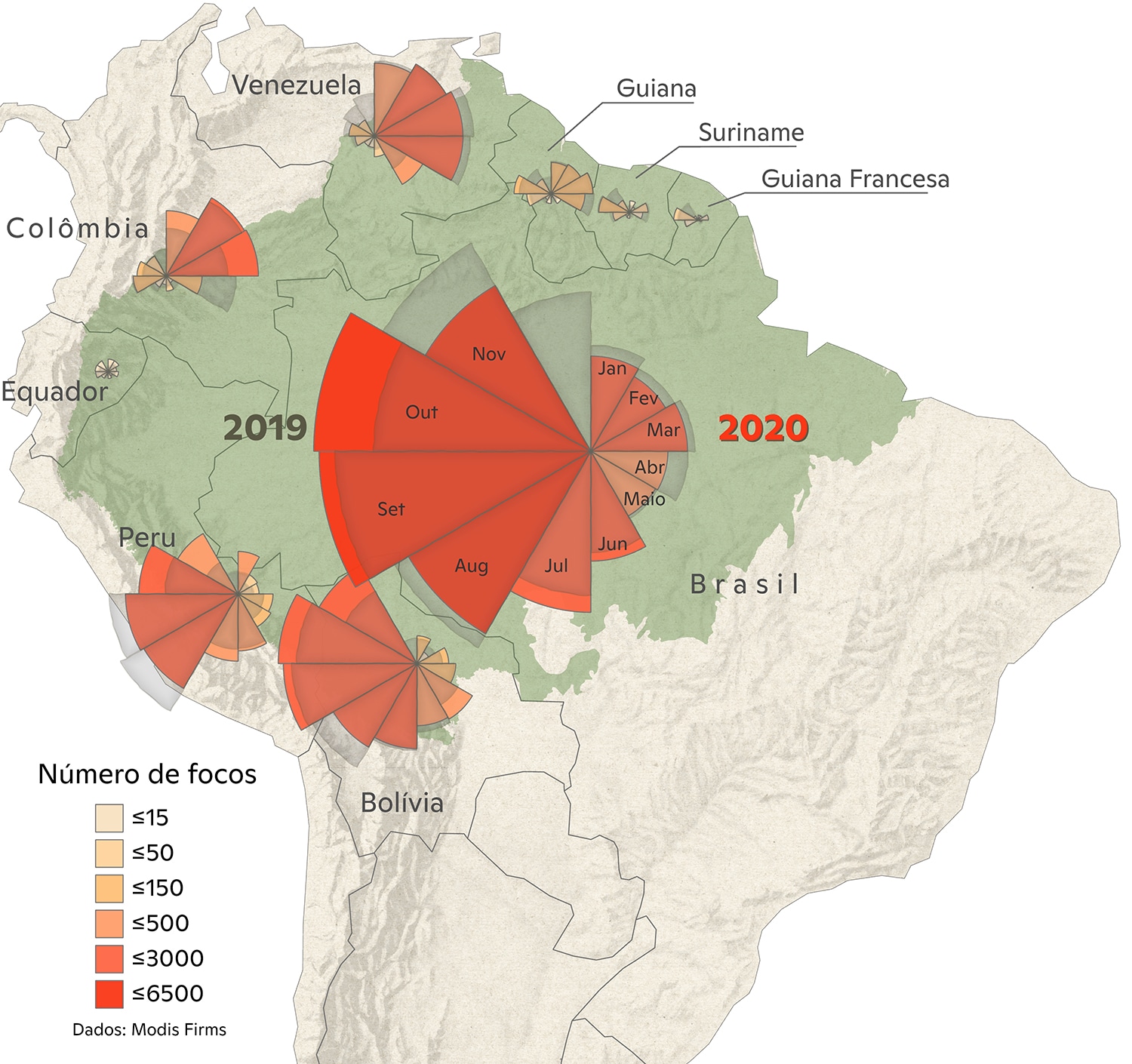

Fires

We counted an additional 3,089 fires in November 2020, which is less than the late season surge of 4,416 fires in 2019. But overall, despite less deforestation this year the total number of fires was 13% greater than 2019, and the most recorded in the last 15 years. This is a direct result of the continued high deforestation rates and the historic drought that has plagued much of Brazil this year.

Learn More

We are using active fires hotspot data based on thermal information acquired from the Modis sensor on board the Aqua satellite with the afternoon daily passage. This is the reference satellite data used by the Brazilian National Space Agency to report fire activity in Brazil. The data is a detection of a fire front of at least 30m width and 1m height. All this information is available at Programa Queimadas Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais.

Committed Carbon

The burning of felled trees following deforestation results in the conversion of carbon previously stored in plant biomass (i.e., in leaves, branches, and stems) to carbon dioxide (CO2), contributing further to the rise in atmospheric CO2 that is the primary driver of planetary warming. In January-November 2020, CO2 emissions committed to the atmosphere as a result of forest clearing are expected to be roughly 299.9 million metric tons (MMT). That’s equivalent to roughly 64.8 million cars and is about ½ of Brazil’s annual total CO2 emissions.

Learn More

Learn more: See Walker et al., 2020, PNAS for details on carbon density calculations.

More Information

Heather Goldstone, Chief Communications Officer

Woodwell Climate Research Center

hgoldstone@woodwellclimate.org, 508-444-1553

Cristina Amorim, Head of Communications

IPAM Amazônia

cristina.amorim@ipam.org.br, +55 (61) 9 9127-6994