Carbon loss from permafrost thaw may be twice as high as thought

Traditional methods of measuring permafrost thaw may be dramatically underestimating vulnerable carbon pools, warns a new study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences by a team of researchers that included Woodwell Arctic Program Director, Dr. Sue Natali. Subsidence, the gradual sinking of terrain caused by the loss of ice and soil mass in thawing permafrost, may result in underestimations of the amount of previously-frozen carbon unlocked from warming permafrost by half.

“These results are a reminder of how much uncertainty there is in our estimates of potential carbon loss from the Arctic and how much more work there is to do,” said Dr. Natali.

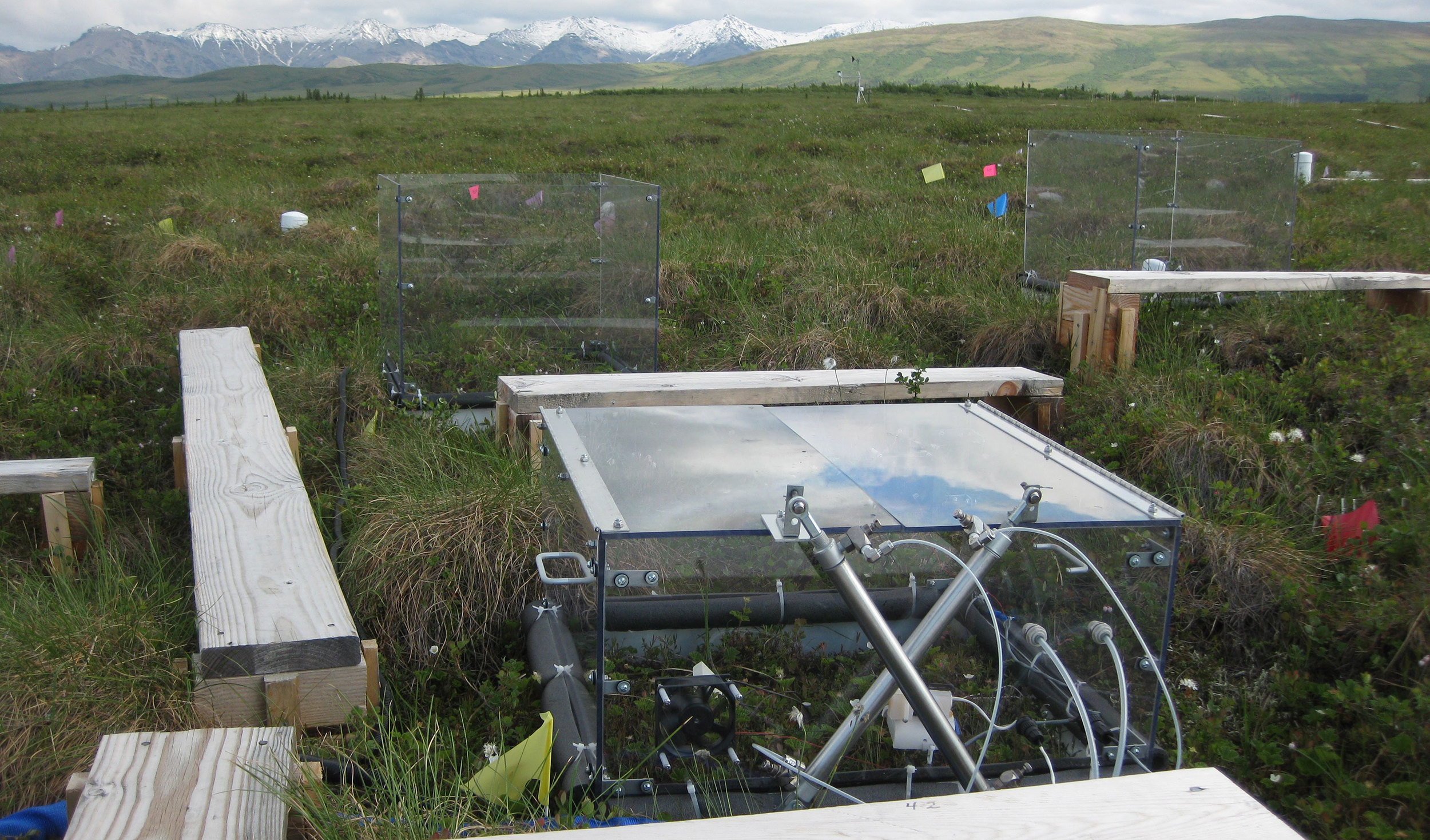

Above: photo by Sue Natali

The study’s participants reflect Woodwell Climate’s deep connections in the Arctic science community. As a postdoctoral researcher in 2008, Dr. Natali helped establish the long-term permafrost warming study that formed the foundation of this research with study co-author Ted Schuur of Northern Arizona University (NAU), who continues to serve as its principal investigator (PI). The experiment warms air, soil, and thaws permafrost using open top greenhouses.

Heidi Rodenhizer, a former student participant in the Polaris Project and now a graduate student working with Schuur at NAU, used the warming experiment to quantify the impact of subsidence on estimates of permafrost thaw. Traditionally, scientists measure ground thaw by putting a metal rod into the ground until it hits solid permafrost, then measuring the depth from the soil surface to frozen ground. However, this method can severely underestimate permafrost thaw when the ground surface has subsided.

Accounting for subsidence, permafrost thawed between 19% (control) and 49% (warming) deeper than previously thought, and the amount of newly thawed carbon within the active layer was estimated to be proportionally greater—37% (control) and 113% (warming). The findings suggest that permafrost is thawing more quickly than some long‐term records may indicate, meaning permafrost’s contribution to climate change is much larger than thought.

“We knew subsidence brought uncertainty to the soil measurements, but these were shockingly high numbers,” said Dr. Natali. “It’s another reminder of the urgency of stopping thaw and protecting as much carbon storage as we can. Even if what we know isn’t perfect, we have all the evidence we need to act boldly to cut fossil fuel emissions.”