“There’s too much fire now”: Fire suppression as a climate solution

For Dr. Kayla Mathes, community perspectives have driven home the need for fire suppression as a tool to protect people and climate

Burned trees in Denali National Park, AK.

photo by Kayla Mathes

When I started at Woodwell Climate, I had very little personal or professional experience with boreal wildfire. I was a forest ecologist drawn to this space by the urgency of the climate crisis and the understanding that northern ecosystems are some of the most threatened and critical to protect from a global perspective. More severe and frequent wildfires from extreme warming are burning deeper into the soil, releasing ancient carbon and accelerating permafrost thaw. Still largely unaccounted for in global climate models, these carbon emissions from wildfire and wildfire-induced permafrost thaw could eat up as much as 10% of the remaining global carbon budget. More boreal wildfire means greater impacts of climate change, which means more boreal wildfire. But when I joined the boreal fire management team at Woodwell, the global picture was the extent of my perspective.

This past June, under a haze of wildfire smoke with visible fires burning across the landscape, Woodwell Climate’s fire management team made our way back to Fort Yukon, Alaska. Situated in Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge at the confluence of the Yukon and Porcupine Rivers, this region is home to Gwich’in Athabascan people who have been living and stewarding fire on these lands for millennia. Our time there was brief, but it was enough to leave us humbled by the reality that the heart of the wildfire story—both the impacts and the solutions—lie in communities like Fort Yukon.

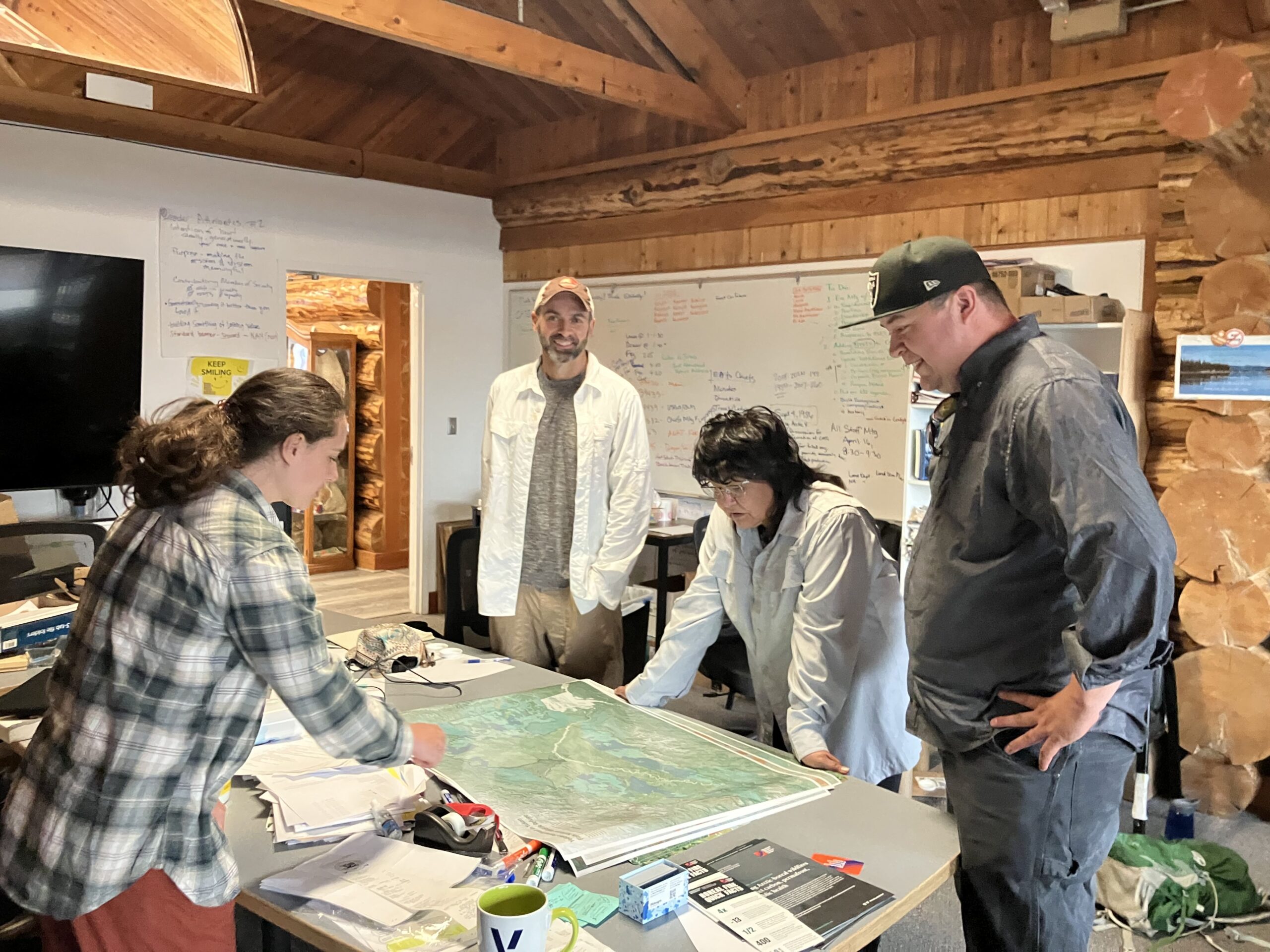

We listened to community members and elders tell stories about fire, water, plants, and animals, all of which centered around observations of profound change over the past generation. As we shared fire history maps at the Gwichyaa Zhee Giwch’in tribal government office, we were gently reminded that their knowledge of changing wildfire patterns long preceded scientists like us bringing western data to their village. We learned that fire’s impact on critical ecosystems also affects culture, economic stability, subsistence, and traditional ways of life. Increasing smoke exposure threatens the health of community members, particularly elders, and makes the subsistence lifestyle harder and more dangerous. A spin on the phrase “wildland urban interface,” Woodwell’s Senior Arctic Lead Edward Alexander coined the phrase “wildland cultural interface,” which brilliantly captures the reality that these fire-prone landscapes, culture, and community are intertwined in tangible and emotional ways for the Gwich’in people.

Mathes, Rogers, Alexander, and Executive Director of the Council of Athabascan Tribal Governments Dorothea Adams examine maps of yedoma permafrost across the Yukon Flats region.

photo courtesy of Kayla Mathes

“There’s too much fire now” was a common phrase we heard from people in Fort Yukon. Jimmy Fox, the former Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge (YFNWR) manager had been hearing this from community members for a long time, along with deep concerns about the loss of “yedoma” permafrost, a type of vulnerable permafrost with high ice and carbon content widespread throughout the Yukon Flats. With the idea originating from a sharing circle with Gwich’in Council International, in 2023 Jimmy enacted a pilot project to enhance the fire suppression policy of 1.6 million acres of yedoma land on the Yukon Flats to explicitly protect carbon and climate, the first of its kind in fire management policy. He was motivated by both the massive amount of carbon at risk of being emitted by wildfire and the increasing threats to this “wildland cultural interface” for communities on the Yukon Flats.

Ever since I met Jimmy, I have been impressed by his determination to use his agency to enact powerful climate solutions. Jimmy was also inspired by a presentation from my postdoctoral predecessor, Dr. Carly Phillips, who spoke to the fire management community about her research showing that fire suppression could be a cost-efficient way to keep these massive, ancient stores of carbon in the ground. Our current research is now focused on expanding this analysis to explicitly quantify the carbon that would be saved by targeted, early-action fire suppression strategies on yedoma permafrost landscapes. This pilot project continues to show the fire management community that boreal fire suppression, if done with intention and proper input from local communities, can be a climate solution that meets the urgency of this moment.

The ultimate vision is for a diverse set of fire management strategies, with a particular focus on the revitalization of Indigenous fire stewardship and cultural burning...

“Suppression” can be a contentious word in fire management spaces. Over-suppression has led to fuel build up and increased flammability in the lower 48. But these northern boreal forests in Alaska and Canada are different. These forests do not have the same history of over-suppression, and current research suggests that the impacts of climate change are the overwhelming driver of increased fire frequency and severity. That said, fire is still a natural and important process for boreal forests. The goal with using fire suppression as a climate solution is never to eliminate fire from the landscape, but rather bring fires back to historical or pre-climate change levels. And perhaps most importantly, suppression is only one piece of the solution. The ultimate vision is for a diverse set of fire management strategies, with a particular focus on the revitalization of Indigenous fire stewardship and cultural burning, to cultivate a healthier relationship between fire and the landscape.

Hazy skies over Fort Yukon, Alaska.

photo by Kayla Mathes

The boreal wildfire problem is dire from the global to local level. But as I have participated in socializing this work to scientists, managers, and community leaders over the past year, from Fort Yukon, Alaska to Capitol Hill, I see growing enthusiasm for solutions that is not as widely publicized as the crisis itself. I see a vision of Woodwell Climate contributing to a transformation in boreal fire management that has already begun in Indigenous communities, one that integrates Indigenous knowledge and community-centered values with rigorous science, and ends with real reductions in global carbon emissions. Let’s begin.