What are Nationally Determined Contributions?

New NDCs raise ambition for emissions reductions, but will countries implement them?

Sunset through smokestack haze.

photo by Brendan O’Donnell/Unsplash

Every 5 years, all 195 signatories of the 2015 Paris Agreement must submit updated plans to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to limit global warming. These plans, known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), are key components of the agreement and represent countries’ highest ambitions for emissions reductions over the next decade.

“The NDC is a pledge,” Director of Government Relations-International at Woodwell Climate Dr. Matti Goldberg says. “It’s a pledge by a government to reduce their emissions by a certain amount, by a certain time frame. It can also be a pledge of taking certain types of actions. Each NDC also contains plans and measures to put it into action.”

This year, countries must submit their third NDC ahead of COP30 in Belém, Brazil.

Stormclouds over the coast of Belem, Brazil

Photo by Tongeron91 / Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0

How do NDCs fit into the Paris Agreement?

The Paris Agreement is a legally-binding international treaty under the UNFCCC. The treaty states that signatories should work together to limit global temperature increase to “well under 2°C” above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to keep the increase below 1.5°C. Nationally Determined Contributions outline how countries plan to achieve this goal and take other measures as part of the global climate effort.

Each NDC must build upon a country’s previous submission and reflect the party’s “highest possible ambition,” according to the Paris Agreement. While parties are legally required to submit an NDC and pursue actions to reach the target, they are “not legally bound to reach the target,” Goldberg says. “It’s a gigantic loophole in a way… although such flexibility is obviously necessary for countries to agree to this, and it does create a structure of pressure.”

After NDCs are submitted, the UNFCCC assesses the combined impact of countries’ NDCs on projected global emissions in a synthesis report. Parties in the Paris agreement also submit a Biennial Transparency Report (BTR) every two years, which outlines each country’s progress made towards accomplishing their NDCs.

“It’s the country’s own assessment,” Goldberg says. “But if a country announces a metric, then others can, of course, also look at whether that metric is being followed. This information creates the basis for civil society and other governments to put pressure on those governments.” Further transparency is created by a process where international experts review each country’s biennial reports.

Despite the ambitious intent of NDCs, Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Simon Stiell determined last November that previous pledges fell “miles short of what’s needed to stop global heating from crippling every economy and wrecking billions of lives and livelihoods across every country.”

What is in the 2025 NDCs?

NDCs were initially due in February 2025, but with only 13 Parties submitting on time, the UNFCCC Secretariat announced a cut-off date in September to have enough time to prepare its synthesis before the start of COP30 in November. China, the United States, India, the European Union, Russia and Brazil were the world’s top emitters in 2023. Together, these six parties accounted for 62.7% of all global emissions. Of the top greenhouse gas emitters, only the U.S. and Brazil sent in their NDCs as of early September 2025.

Are we moving the needle here or not? How much are we moving the needle? Are we moving it enough to avoid 2°C?Dr. Abby Lute, Research Scientist

The United States submitted its NDC in 2024 under the Biden Administration and set a target of reducing its net greenhouse gas emissions by 61 to 66% below 2005 levels in 2035. After taking office, President Trump issued an executive order announcing the U.S.’s intent to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, which will go into effect in 2026. After January 2026, the U.S. will no longer be required to submit new NDCs or Biennial Transparency Reports.

Despite the country’s withdrawal, Goldberg says the U.S. may see a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions because of its continuing transition from coal to natural gas, renewables and nuclear power—which, according to Goldberg, is driven more by economics and less by policy. Still, Dr. Christopher Schwalm, Vice President of Science at Woodwell Climate, predicts there is “no way” the United States will hit the targets set out in the NDC given the current global political climate. Even if the U.S. does reach its goals, the NDC still does not align with the global 1.5°C limit, according to the Climate Action Tracker. Schwalm calls the 1.5°C target “dead as a doornail.” To reach this goal, we would have needed global greenhouse gas emissions to peak by 2025.

Brazil’s most recent NDC states a goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions 59% to 67% compared to its 2005 emissions. Goldberg calls it a “pretty ambitious” absolute target for a country classified as a developing country under the UNFCCC. However, the Brazilian climate organization Observatório do Clima states the NDC goals do not align with the global 1.5°C limit.

How could reaching targets in NDCs impact warming trajectories?

Woodwell Climate research scientist Dr. Abigail Lute wanted to see how much of a difference just two of the top-emitting countries’ NDCs could make.

“Are we moving the needle here or not?” she says. “How much are we moving the needle? Are we moving it enough to avoid 2°C? That’s the big picture, to see how ambitious these new pledges are.”

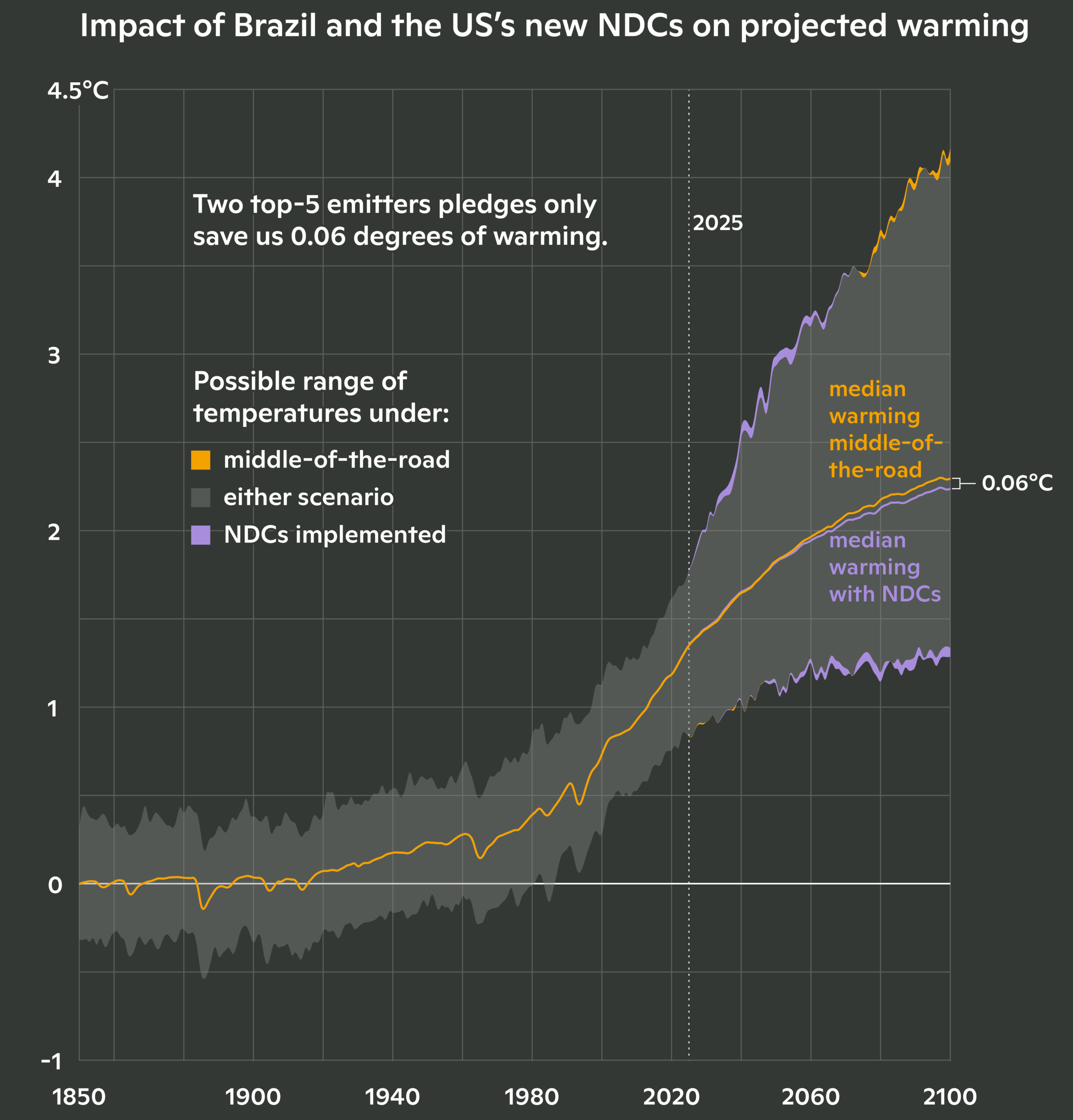

Lute modeled how both the U.S. and Brazil’s promises together could change the global warming trajectory using a “middle-of-the-road” scenario for future greenhouse gas emissions—though, at the moment, that scenario might be more optimistic than our current trajectory, she says.

For the first 10 to 20 years after implementing the NDCs, temperatures will temporarily increase. This is due to the reduction in polluting gases such as sulfates that actually have a cooling effect in the atmosphere. After about a decade or two, the reduction in warming gases such as methane and carbon dioxide will cause temperatures to fall.

Impact potential of implementing NDCs.

graph by Christina Shintani

According to Lute’s calculations, under moderate emissions scenarios, the probability of exceeding 2°C is 25% by 2050 and 78% by 2100. If both the U.S. and Brazil reach their NDC targets, the probability of exceeding 2°C stays about the same for 2050 but drops down to 73% for 2100.

Global warming is expected to reach 1.8°C by 2050 and 2.3°C by 2100 under the medium emissions scenario. With the U.S. and Brazil’s combined NDCs, Lute expects warming to be reduced by about 0.01°C in 2050 and 0.06°C by 2100.

While these contributions may seem small, Brazil and the U.S. only represent two of the 195 parties in the Paris Agreement.

“It’s two of the larger ones for sure, but it’s only two,” Lute says. “If we extrapolate it to everybody, then it can make a meaningful difference… the story here is that everybody needs to contribute. This is a collective problem, and even one large country can’t solve it.”