Indigenous fire brigades partner with geospatial tech to fight fires in the face of climate change

Knowledge-sharing workshops offer skills, opportunities, and a pathway to protect their homes from wildfires

Brigadista Terena Neudines Felix from the Brigada Taunay Ipegue, Aquiduana, Pantanal, Mato Grosso do Sul state.

photo by Alicce Rodrigues/Instituto Terra Brasilis

September 2025— On the shores of Lago Caracaranã, deep in the Brazilian State of Roraima, a group of Indigenous brigadistas gather around printed paper maps. They have come to this lakeside meeting place from their territories across the state and beyond to learn about maps from Dr. Ray Pinheiro Alves, a research analyst at the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM). Alves directs each woman to a map of their own territory, completely unlabeled. He hands them drawing supplies, and within moments the brigadistas have oriented perfectly to the map, tracing familiar rivers, home sites, and landmarks from memory.

Roraima is Brazil’s northernmost state. It straddles the equator, and contains both native sweeping grasslands like those around Caracaranã and misty, mountainous stretches of the Amazon rainforest. It is remote, and sometimes disconnected from the rest of the country, yet experiencing the same encroachment from agriculture and illegal mining, and the same increase in destructive fires that often follow in the wake of deforestation. Which is why the Indigenous fire-fighting brigades here are eager to pick up new tools that could help them manage and protect their forests and homes.

map by Christina Shintani

Alves believes maps should be one of those tools. He, along with Woodwell Climate research scientist, Dr. Manoela Machado, has been spearheading a series of workshops designed to help Indigenous fire brigades build the skills of cartography and geographic information systems (GIS). Strong GIS knowledge allows fire crews to make use of data to guide decisions about both on- and off-season fire management activities— both of which will become more critical as the climate warms and fire becomes more prevalent and difficult to control.

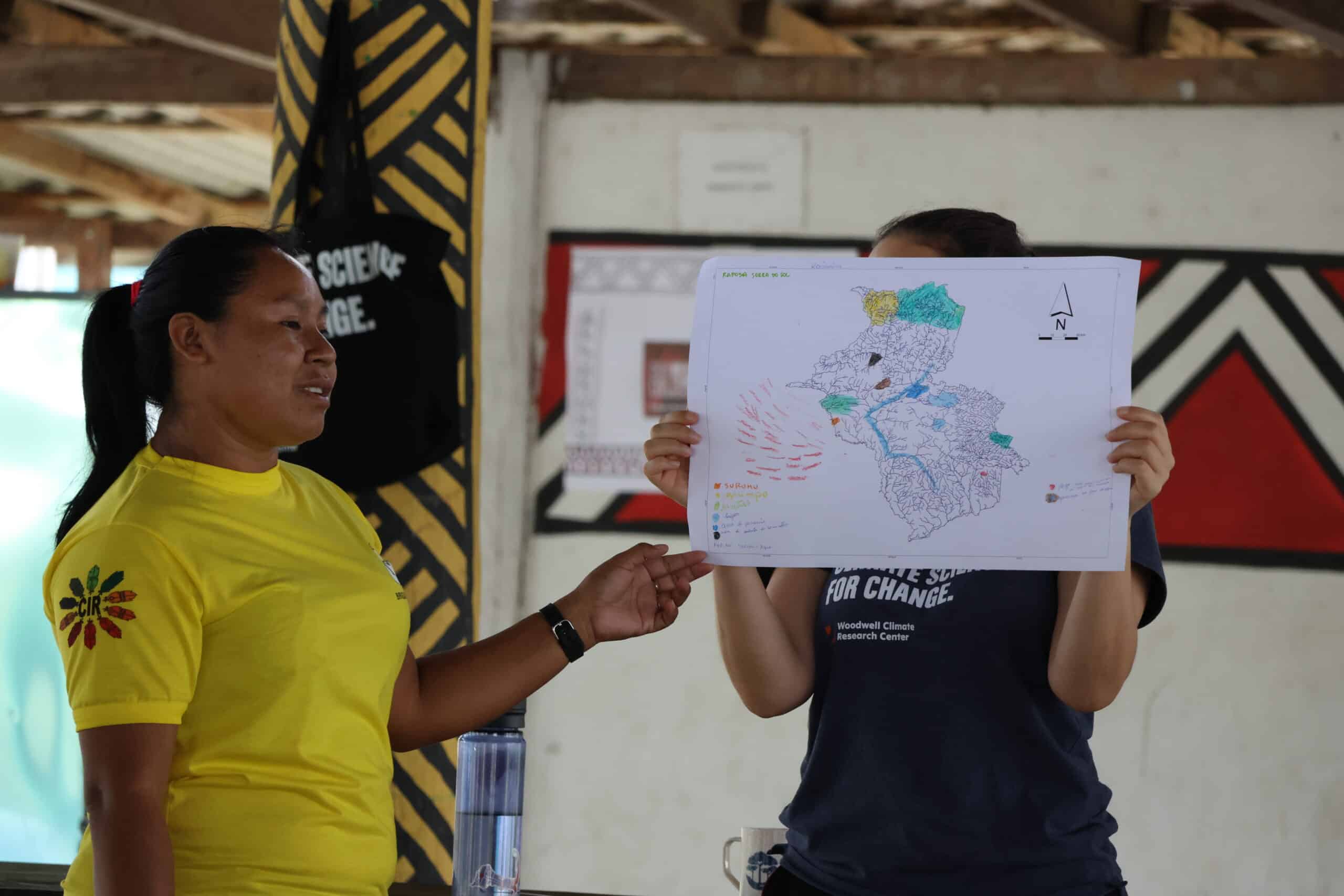

Brigades present their hand-drawn maps during the workshop’s mapmaking session.

photos by Sara Leal Pereira/IPAM

Brazil’s fiery landscape

It is supposed to be raining in Roraima right now, but the winter has been dry this year. Climate change has been elongating dry seasons in many regions of the country, increasing the time that ecosystems are prone to burning.

In the Amazon, fires are set intentionally as a part of the deforestation process. Land grabbers use fire to clear the piled vegetation that was cut to make way for cattle ranching, which later will be converted to cropland. With climate shifts, these fires are now more likely to escape into drier and weakened surrounding forests. In Central Brazil, the savana and seasonal wetland ecosystems of the Cerrado and Pantanal have co-evolved with varying levels of frequency and intensity of fire. But prolonged drought and rising temperatures have turned fire seasons into crisis seasons.

Indigenous communities across Brazil have used fire for millennia, working with the ecosystem to promote culturally important species. With climate change extending fire seasons, traditional calendars are also shifting, as the time available for safe burning shrinks. Communities are also facing incursions into their territories from runaway fires ignited on nearby farms.

Fire in Chapada dos Guimarães in Mato Grosso, adjacent southwest to Tocantins.

photo by Manoela Machado

The world got a taste of the scope of the crisis in 2019 when, during an already record-breaking summer of fire, land grabbers in the Amazon intentionally set so many fires in a single day that the smoke traveled to the City of São Paulo hundreds of miles away.

“The sky in São Paulo became dark at 3pm. And then the world started paying attention to fires in the Amazon,” says Machado. Protecting Brazil’s forests from fire, especially the carbon-rich Amazon rainforest, became a much higher priority for the international community.

Brazil has an extensive wildland fire fighting system, composed of both official and voluntary brigades, supported by various government agencies to operate across private lands, protected public lands, and Indigenous territories. Amidst the increased urgency to quell fires, Machado was interested in understanding what brigades at different jurisdiction levels might need to be more effective during crisis months. She herself has extensive expertise in geospatial software and analysis and wondered whether organizations like Woodwell Climate and IPAM could help by providing data on terrain, weather patterns, vegetation type, and other field-relevant information.

So Machado and Senior Scientist Dr. Marcia Macedo, conducted a needs assessment of the firefighting system to identify what analyses might be most useful.

“The answer was a little bit different, depending on who we were talking to,” says Macedo. “But when we spoke to the Indigenous fire brigades, one of the things that came out right away was not just a desire for spatial data, but for training in spatial analysis. They wanted to be able to work with the data the same way we did.”

Two ways of knowing the land

For the Indigenous communities of Brazil, maps aren’t needed for navigating their territory the way Google Maps might be for someone walking in unfamiliar lands.

“The Indigenous peoples of Brazil have a great understanding of their territory,” says Alves. “We show them an image and they recognize some river or some landmark. They can see it immediately in the satellite view.”

Instead, geospatial data offers another way of communicating their innate knowledge of the land. For the Indigenous fire brigades Machado and Macedo spoke with, the ability to use the same GIS tools that scientists use, and make maps the way a government agency like Brazil’s Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) might, is invaluable to advocating for themselves in non-Indigenous spaces.

“To be able to make their own maps can strengthen their autonomy to make decisions, and [aid in] dialogs with people about public policies,” says Alves.

Manoela Machado provides instruction to workshop participants learning how to use GIS.

photo by Sara Leal Pereira/IPAM

Machado worked with Alves to develop the curriculum for a series of workshops that would help teach the foundations of GIS to fire brigade members from Indigenous territories across Brazil. The first was held in Brasília in 2022, and three more have followed since, the class in Roraima most recently.

Each workshop begins with the basics—latitude and longitude, hemispheres, projections. Alves is a natural teacher, and makes use of props, metaphors, and activities like drawing on the printed maps to make the concepts feel more tangible.

On later days of the workshop, as participants get familiar with QGIS, a free map-making software, Alves sometimes adapts the suggested curriculum to the needs of the communities in attendance.

“For example, in one class we were presenting topographic maps, and they said ‘this is really, really, useful for us,’” says Alves. “So we changed that part of the course to solve for the question they were dealing with.”

By the end of the course, participants have successfully created maps relevant to their own territories. Seeing their own homes represented in map form, Machado says, connects them more strongly to the material.

“You could see the pride on their face,” Machado says. “They recognize every element of that map because they built it. They made each decision of what to show on the map.”

A brigadista at the Roraima workshop presents her map.

photo by Sara Leal Pereira / IPAM

The women’s brigade

Ana Shelley Xerente of the Xerente people had watched her husband work on their territory’s official fire brigade for 13 years before she decided she’d like to try her hand at it as well. Over the years raising her two children, she observed changes occurring in the native Cerrado ecosystem of the Xerente territory—hotter temperatures, drying streams, more fires.

“Nowadays, right after the rain, it’s basically dry,” says Ana Shelley. “All due to climate change.”

She felt a strong duty to protect the environment, and told her husband she’d like to work at Prevfogo, the firefighting arm of Brazil’s Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA), like him.

“He kept teasing me. ‘There’s no way you could handle that,’” Ana Shelley says. “But I kept talking about it and he came up with the idea of creating a volunteer brigade.”

Volunteer brigades support official brigades, including with that critical non-crisis season prevention work. In 2021, responding to interest from Ana Shelley and others in the territory, Prevfogo and the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) provided support to start an all-woman volunteer brigade— the first in Brazil. Ana Shelley drove her team of 29 women from village to village, speaking to elders, educating children, re-planting vegetation around headwater streams, and discussing how climate change has affected their traditional calendar for cultural burning.

The women’s brigade of Xerente performs outreach to community members within their territory.

photo courtesy of Ana Shelly Xerente

“We have our own calendar, made by our elders. It marks the rainy season and the dry season, when burning isn’t allowed. So we went through the whole territory, talking to people about what fire brings, the impact it has on humans and animals, and there was a significant reduction [in fires],” Ana Shelley says.

Ana Shelley began to stand out as a leader among the volunteers. In 2024, when her husband left his role as president of the official territory brigade to pursue work with FUNAI, she was asked to fill in for the remainder of his term. At the start of 2025, she was named president for her own four-year term, and has eagerly assumed the responsibility of organizing the activities of 74 Indigenous firefighters, both men and women.

“Everything is new to me, being a brigade chief. And since in our community it’s mostly men who call the shots, it causes an impact, because now the chief is a woman, so it’s all new to them, too,” Ana Shelley says. “I learn a lot from them, and I also share with them what I know. I’m sure it’s going to be challenging, but I also know it’s going to bring a lot of good results.”

Ana Shelley Xerente (center) stands with her fellow brigade members for a selfie.

photo courtesy of Ana Shelley Xerente

Classroom representation

The second GIS workshop was hosted in Ana Shelley’s own territory in Tocantins, but only her husband participated in the course. In fact, midway through the workshop, Machado looked around and wondered why, in a territory with an established brigade of motivated female fire fighters, she was the only woman in the classroom.

Despite not being in operation for as long as the men’s brigades, the brigadistas were eager to perform at the same level. Perhaps, Machado wondered, the workshops could be an opportunity to level the playing field.

She suggested hosting a women’s-only brigade training to encourage their participation, giving women a chance to learn alongside others with similar experiences. The first one took place in Maranhão in June, followed by the one in Roraima.

Macedo says this kind of peer representation is critical to the success of capacity sharing efforts like this one.

“Peer-to-peer teaching and knowledge sharing among people who are living the same reality is almost always more effective than us scientists standing at the front [of a class],” Macedo says.

A young woman participant of the communications sessions of the 2025 workshop presents during the final remarks.

photo by Sara Leal Pereira / IPAM

The brigadistas of Roraima are the clear result of women’s representation on fire brigades, which started in Tocantins with Ana Shelley and has now unfurled across the country. Roraima was the first Brazilian state to formalize all-female fire brigades with the Brigada Pataxibas— a multi-territory collective of female firefighters. During the closing ceremony for the workshop in Roraima a Tuxaua, or elderly community member honored for their wisdom, named Azila stood to point out the bravery of the women assembled, who had accomplished things she never had the opportunity to do in her youth.

Brigade participation has also begun to open doors for women even beyond their territories.

“Some have become teachers, others are in college. It has broadened their horizons. We’ve inspired many women across Brazil,” says Ana Shelley.

According to Machado, the GIS training offers all participants, men and women, the opportunity to tell their own stories on their own terms.

“Maps tell stories,” says Machado. “So the importance of all community members being able to build their own maps is that it allows them to control the narrative. They control how their story is told, instead of waiting for someone else to build a map and tell the story for them.”

The future of fire management

For now, the workshops are planned and hosted on an ad hoc basis, as funding allows. But Macedo sees a pressing need to scale up. The more brigades participate, the more excitement grows for the material.

“If we offered one of these a month for a while, we still wouldn’t be able to meet the demand for them,” says Macedo.

(above) Indigenous brigade members in uniform.

(Below) The cohort of participants at the 2025 workshop in Roraima

photos by Sara Leal Pereira / IPAM

At some point, Macedo says, the project will have to shift to a “training the trainers” strategy. The team envisions a model where the most engaged workshop participants are taught the skills needed not just to make maps but to teach others, expanding this knowledge further and faster than Alves, Machado, and Macedo could on their own. Technology access is another limiter. Some Indigenous communities have access to laptops at central headquarters but it is not common for each community to have its own laptop and almost no individual brigade members do. More laptops would allow workshop participants to continue practicing their skills on their own time.

Policies in Brazil have also begun to shift to open additional opportunities. In 2024, the country passed a new Integrated Fire Management law that will require greater coordination among different brigade jurisdictions for pre-season and mid-season firefighting activities. The law places a specific emphasis on incorporating traditional knowledge. Macedo says she thinks the GIS workshops could contribute to this greater movement and help position Indigenous communities as central to the country’s fire management policies.

When Ana Shelley reflects on how much her brigades have already been able to accomplish, and the possibilities on the horizon, she is hopeful.

“I see a much better future.”