US forests hold climate keys

The UN climate summit in Glasgow ended with more words than actions as global emissions are the second-highest on record and the world is on track for an increase of another 16 percent by 2030.

Alarmingly, global deforestation is occurring at a rate of 27 football fields every minute of each day. Recognizing this loss, President Biden pledged that the United States will “help the world halt natural forest loss and restore at least an additional 494 million acres by the year 2030.”

As it stands, the Biden administration’s climate plans say nothing about ending forest losses right here at home by protecting climate-saving older forests and trees on federal lands. It’s a glaring omission that needs to be fixed.

Read the full article on The Hill.

Climate Risk Assessment: Belém, Pará, Brazil

Introduction

The impacts of climate change on frequency and severity of physical hazards will put many communities at risk.

The impacts of climate change on frequency and severity of physical hazards will put many communities at risk.

As the threat of climate change grows, so too does the need for accessible information, tools, and expertise to support climate resilient decision-making for municipalities. In the newly released report Recognizing Risk—Raising Climate Ambition,

Woodwell highlights the need to localize and customize climate risk assessments. However, the private sector is meeting the majority of the need for climate data and analyses, reducing access for communities without sufficient financial resources. To address this gap, Woodwell works with communities across the world, including Belém, Pará, in Brazil, to provide granular climate services, free of charge.

Results

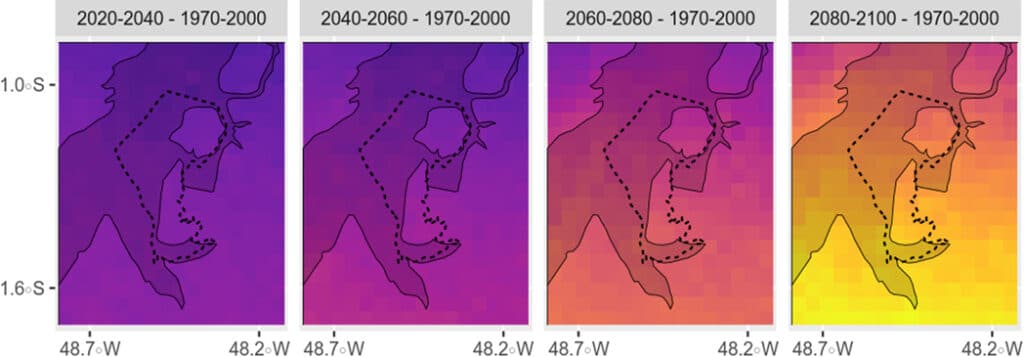

Figure 1: Change in Temperature Annual Range

This figure shows future changes in the difference between the highest maximum temperature and the lowest minimum temperature within a year relative to 1970-2000. Higher values indicate that the difference (how much temperatures “spread” within a year) will increase over time. We can see that the hot months of the year will get hotter and cold months colder.

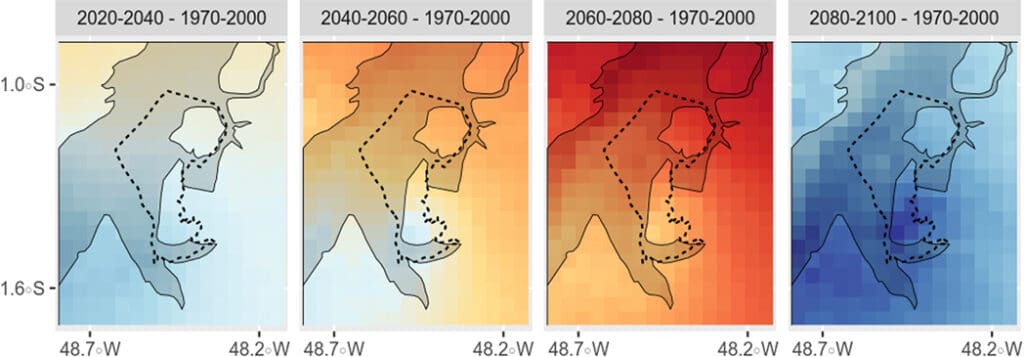

Figure 2: Change in Precipitation of Wettest Month

This figure shows future changes in the precipitation of the wettest month of a year relative to 1970-2000. Higher values indicate that that the wettest month will become wetter over time. Notice that the ensemble of models project a reduction of precipitation until 2060-2080 (first three maps), and after that, an abrupt increase (last facet).

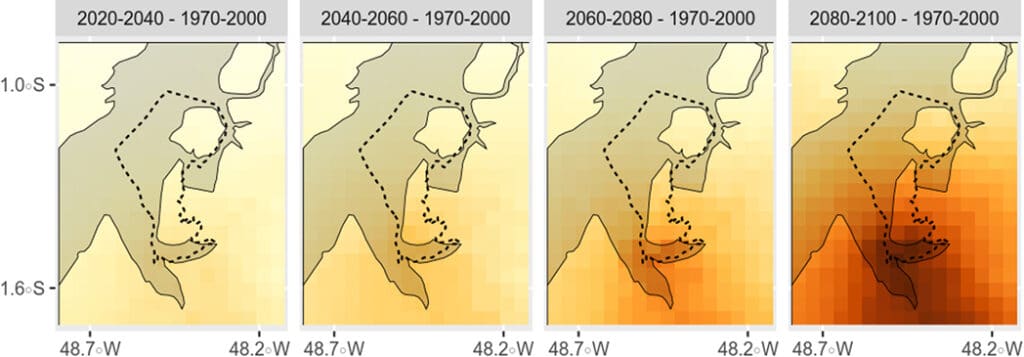

Figure 3: Change in Precipitation of Driest Month

This figure shows future changes in the precipitation of the driest month of a year relative to 1970-2000. Higher values indicate that the driest month will become drier over time.

Figure 4: Change in Length of Fire Season in Pará

This figure shows future changes in the length of the fire season in the state of Pará relative to 1970-2000. Higher values indicate an increase (in days) of such length, and thus, more risk of wildfires. This figure highlights Belém’s exposure to worsening air quality over time.

Figure 5: Wet-Bulb Temperature

This figure shows historical and future frequency of days/year over 28 °C of wet-bulb temperatures. Wet-bulb temperature is a “feels-like” temperature indicator (strictly speaking, it is defined as the air temperature at 100% relative humidity). A wet-bulb temperature of 28 °C is considered dangerous for humans; continued exposure to it can lead to severe heat stress.

Quick talk with Dr. Rachel Treharne of the Woodwell Climate Research Center

Permafrost in the polar regions has been storing carbon for millennia. As the planet warms, permafrost thaw threatens to unleash that carbon back into the atmosphere, launching a potentially devastating feedback cycle that could accelerate warming even more. Yet that risk is not included in current global carbon budget accounting. I spoke with permafrost expert Rachael Treharne, from the U.S.-based Woodwell Climate Research Center, about what is at stake.

For full interview, read the Times newsletter.

Addressing climate risk with the COP26 Presidency

The 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference UK Presidency and Woodwell Climate convened a series of climate risk workshops with 13 countries. The findings demonstrate the global need for targeted, standardized assessments that translate the severe risks and hazardous impacts of climate change on people’s daily lives.

COP26 will turn its focus to science and innovation

Transforming scientific action into adaptation strategies is crucial for climate resilience

One of COP26’s official themes on Tuesday, along with gender, is “science and innovation.” While a dauntingly broad theme in the context of climate change, the goal at the summit is straightforward: turn information into action. Scientists and negotiators will convene to discuss how to translate a wealth of climate science into climate resilient strategies for decision-makers and their communities.

Read the full article on Washington Post.

Recognizing risk—raising climate ambition

To make good decisions about responding to climate change, it is crucial that we understand the full scale of the risk.

The 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) brought countries together to accelerate action towards the goals of the Paris Agreement and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). To date, however, progress with both national climate change mitigation policy and sub-national adaptation strategy have not matched the severe risks of impending climate change impacts, implying that climate risks are not being communicated and received effectively.

Currently, many climate risk assessments focus on a single hazard, cover large spatial and temporal scales, and often only look at global and national impacts through the end of the century. Climate risks are frequently shown as a function of various future emissions scenarios, which can be a source of confusion and uncertainty. There is still an enormous gap between our understanding of climate risk and climate policy ambition.

In this context, the COP26 Presidency and Woodwell Climate Research Center (“Woodwell”) organized country-specific workshops to understand how to better deliver climate risk information. We gathered high-emitting nations (Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, India, Indonesia, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, South Africa, United States, and Turkey); collectively, these nations comprise approximately 67% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. We convened more than 220 cross-sectoral experts in climate policy, science, resilience, and advocacy, as well as those working in financial risk, to discuss both general perceptions of climate risks and specific aspects of climate risk assessments. Following these workshops, the conversations were distilled to identify the themes that emerged across all workshops, and those that were unique to individual countries. Our goals were to identify both the aspects of climate risk assessments that are most effective at motivating action and those that could be improved. With this report, we address both scientists who have traditionally been involved in the climate risk assessment process, and experts, stakeholders, and decision-makers who for the most part, have not.

To produce these findings, Woodwell researchers synthesized detailed notes from each workshop to identify common themes, challenges, and suggested solutions. The document aims to deliver insight to the scientific community about how climate risk assessments for policymakers can be designed and delivered more effectively.

Details on cross-cutting themes that emerged from many or all of the workshops can be found in the downloadable full report.

Beyond 1.5: Just in Case: What do we need to know about climate intervention?

The best available science strongly suggests that even rapid decarbonization and carbon drawdown may not be enough–or happen soon enough–to avoid tipping points and catastrophic climate outcomes. Yet, even discussing large-scale climate engineering remains taboo. This groundbreaking event poses critically important questions such as: What do we know about geoengineering? Can we afford to ignore it? What might make it worth considering such drastic measures? And what more would we need to know in order to make an informed choice?

Watch the video recording.

Brazilian farmers who protect the Amazon rainforest would like to be paid

Invaldo Weis acknowledges he is the kind of farmer some environmentalists love to hate: In the 1970s, he carved out an 11,700-acre soy-and-cattle farm by clearing trees in the Amazon jungle.

But the 65-year-old Brazilian and thousands of farmers like him could also be crucial allies for environmentalists in stopping further destruction of the world’s biggest tropical forest and help slow rising global temperatures.

Read the full article on the Wall Street Journal.