Unchecked boreal forest fires are eating into our carbon budget

Proper management could be a cost-effective solution

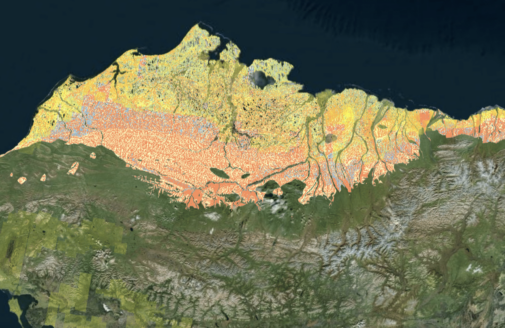

Fire in interior Alaska black spruce forest, 2009.

photo by Eric Miller

What’s new?

A recent paper, published in Science Advances, has found that fires in North American boreal forests have the potential to send 3 percent of the remaining carbon budget up in smoke. The study, led by Dr. Carly Phillips, a fellow with the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), in collaboration with the Woodwell Climate Research Center, Tufts University, the University of California in Los Angeles, and Hamilton College, found that burned area in U.S. and Canadian boreal forests is expected to increase as much as 169 and 150 percent respectively—releasing the equivalent annual emissions of 2.6 billion cars unless fires can be managed. The study found proper fire management offers a cost-effective option, sometimes cheaper than existing options, for carbon mitigation.

Understanding boreal forest carbon

Boreal forests are incredibly carbon rich. They contain roughly two-thirds of global forest carbon and provide insulation that keeps permafrost soils cool. Burned areas are more susceptible to permafrost thaw which could in turn release even more carbon into the atmosphere. Although fires are a natural part of the boreal ecosystem, climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of them, which threatens to overwhelm the forest’s natural adaptations.

Researchers burn away fuel to manage fire spread (left) and study burn severity after fire (right)

photos by Dale Haggstrom

Despite the value of boreal forests for carbon mitigation, the U.S. and Canada spend limited amounts of funding on fire suppression, usually prioritizing fire management only where people and property are at risk. Alaska accounts for one fifth of all burned area in the U.S. annually, but it receives only 4 percent of federal funding for fire management. Limiting fire size and burned area through proper management can be effective at reducing emissions.

Governments rightly prioritize rapid suppression of wildfires that occur near heavily populated areas and crucial infrastructure, but allowing areas that hold large amounts of carbon to burn could also prove extremely hazardous to the health and safety of people living in the U.S., Canada and beyond.Dr. Carly Phillips, Union of Concerned Scientists fellow

What this means for boreal fire management

To prevent worsening emissions, fire management practices will have to be adjusted to not only protect people and property, but also to address climate change. Fire suppression in boreal forests is an incredibly cost-effective way to reduce emissions. The study found that the average cost of avoiding one ton of carbon emissions from fire was about $12. In Alaska, that means investing an average of just $696 million per year over the next decade to keep the state’s wildfire emissions at historic levels.

Increasing wildfires also pose an outsized threat to Alaska Native and First Nations communities, who may become increasingly isolated, and may lack the resources to evacuate quickly if wildfire encroaches on their lands. Many Alaska Native people already play a crucial role in existing wildfire crews, and investing in more fire suppression could create additional job opportunities for Indigenous communities.

Reducing boreal forest fires to near-historic levels and keeping carbon in the ground will require additional investments. These funds are comparatively low, and pale in comparison to the costs countries will face to cope with the growing health consequences exacerbated by worsening air quality and more frequent and intense climate impacts expected if emissions continue to rise unabated. They can also ensure wildlife, tourism, jobs, and many other facets of our society can persevere in a warming world.Dr. Brendan Rogers, Woodwell Associate Scientist and co-author of the study