Global forest carbon storage, explained

Protecting forests is one of our best climate solutions. Here’s how forests around the world store carbon.

Flooded lowland rainforest in Brazil.

photo by Mitch Korolev

When it comes to reversing climate change, trees are a big deal. Globally, forests absorb nearly 16 billion metric tonnes of carbon dioxide per year, and currently hold 861 gigatonnes of carbon in their branches, leaves, roots, and soils. This makes them a valuable global carbon sink, and makes preserving and maintaining healthy forests a vital strategy in combating climate change.

But not every forest absorbs and stores carbon in the same way, and the threats facing each are complex. A nuanced understanding of how carbon moves through forest ecosystems helps us build better strategies to protect them. Here’s how the world’s different forests help keep the world cool, and how we can help keep them standing.

Rainforest trail in the Brazilian Amazon.

photo by Sarah Ruiz

Tropical forest carbon

Tropical rainforests are models of forest productivity. Trees use carbon in the process of photosynthesis, integrating it into their trunks, branches, leaves, and roots. When part or all of a tree dies and falls to the ground, it is consumed by microorganisms and carbon is released in the process of decay. In the heat and humidity of the tropics, vegetation grows so rapidly that decaying organic matter is almost immediately re-incorporated into new growth. Nearly all the carbon stored in tropical forests exists within the plants growing aboveground.

Studies estimate that tropical forests alone are responsible for holding back more than 1 degree C of atmospheric warming. 75% of that is due simply to the amount of carbon they store. The other 25% comes from the cooling effects of shading, pumping water into the atmosphere and creating clouds, and disrupting airflow.

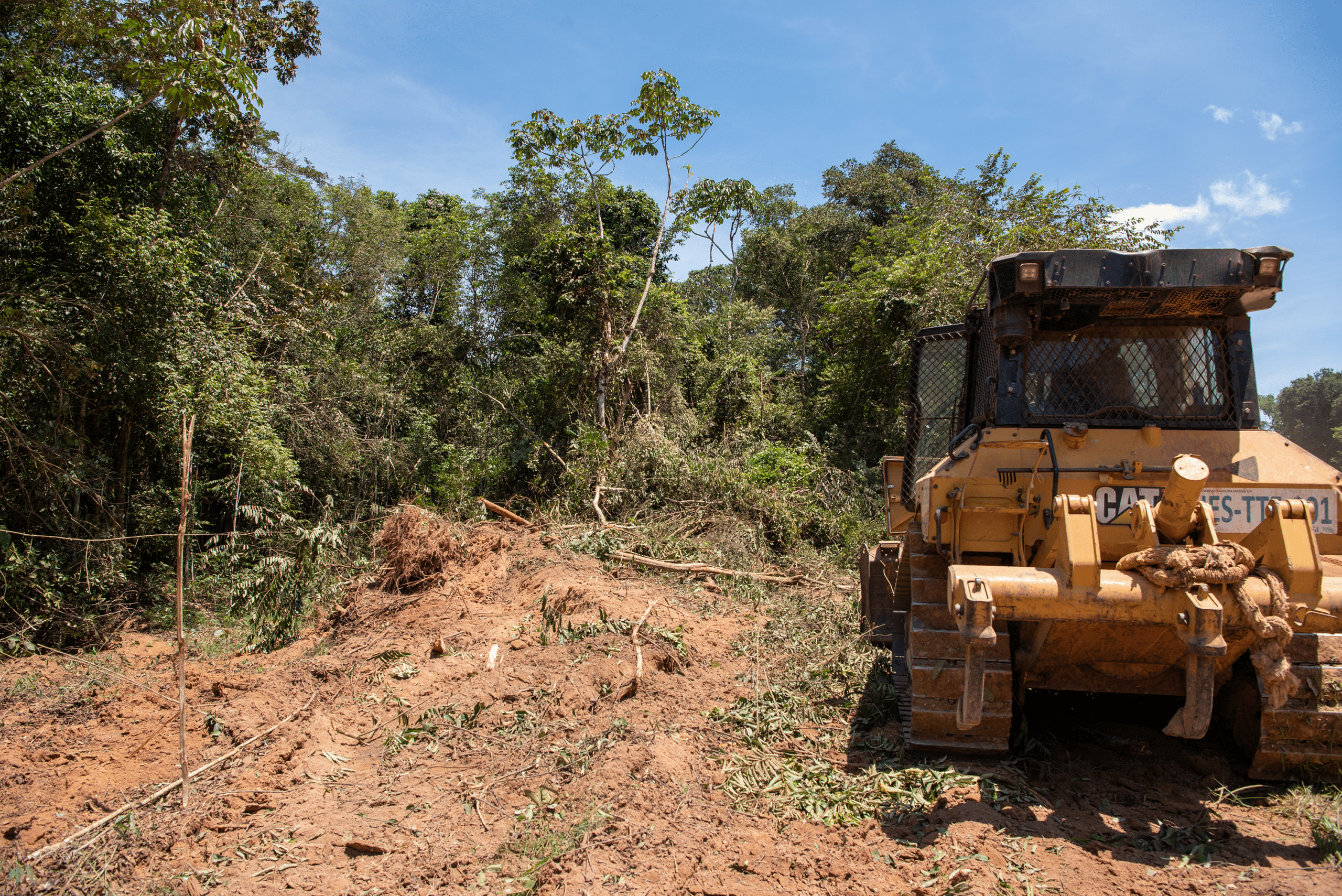

In many tropical forest regions, there is a tension between forests and agricultural expansion. In the Amazon rainforest, land grabbing for commodity uses like cattle ranching or soy farming has advanced deforestation. Increasing protected forest areas and strengthening the rights of Indigenous communities to manage their own territories has proven effective at reducing deforestation and its associated emissions in Brazil. “Undesignated lands” have the highest levels of land grabbing and deforestation.

Bulldozer used to clear rainforest in Mato Grosso, Brazil.

photo by Mitch Korolev

Fire has also become a growing threat to the Amazon in recent years, used as a tool to clear land by people illegally deforesting. When rainforests have been fragmented and degraded, their edges become drier and more susceptible to out-of-control burning, which weakens the forest even further. Enforcing and strengthening existing anti-deforestation laws are crucial to reduce carbon losses.

In Africa’s Congo rainforest, clearing is usually for small subsistence farms which, in aggregate, have a large effect on forest loss and degradation. Mobilizing finance to scale up agricultural intensification efforts and rural enterprise within communities, while implementing protection measures, can help decrease the rate of forest destruction. Forests and other intact natural landscapes such as wetlands and peatlands could be the focus of climate finance mechanisms that encourage sustainable landscape management initiatives.

Forest cleared for timber harvest in Maine.

photo by Jonathan Kopeliovich

Temperate forest carbon

Much of the forest carbon in the temperate zone is stored in the trees as well—particularly in areas where high rainfall supports the growth of dense forests that are resilient against disturbances like drought or disease. The temperate rainforests of the Northwestern United States, Chile, Australia, and New Zealand contain some of the largest and oldest trees in the world.

Two thirds of the total carbon sink in temperate forests can be attributed to the annual increase in “live biomass”, or the yearly growth of living trees within the forest. This makes the protection of mature and old-growth temperate forests paramount, since older forests add more carbon per year than younger ones and have much larger carbon stocks. Timber harvesting represents one of the most significant risks to the carbon stocks in temperate forests, particularly in the United States where 76% of mature and old growth forests go unprotected from logging. Fire and insects are also significant threats to temperate forests particularly in areas of low rainfall or periodic drought.

Maintaining the temperate forest sink means reducing the area of logging, by both removing the incentive to manage public forests for economic uses and by providing private forest owners with incentives to protect their land. Low-impact harvesting practices and better recycling of wood products can also help bring down carbon losses from temperate forests. In areas threatened by increasingly severe wildfires, reducing fuel loads especially near settlements can help protect lives and property.

Close up on the boreal forest floor.

photo by Brendan Rogers

Boreal forest carbon

In boreal forests, the real wealth of carbon is below the ground. In colder climates, the processes of decay that result in emissions tend to lag behind the process of photosynthesis which locks away carbon in organic matter. Over millennia, that imbalance has slowly built up a massive carbon pool in boreal soils. Decay is even further slowed in areas of permafrost, where the ground stays frozen nearly year round. It estimated that 80 to 90% of all carbon in boreal forests is stored belowground. The aboveground forest helps to protect belowground carbon from warming, thaw, decay, and erosion.

Wildfire—although a natural element in boreal forests—represents one of the greatest threats to boreal forest carbon. With increased temperatures, rising more than twice as fast in boreal forests compared to lower latitudes, and more frequent and long-lasting droughts, boreal forests are now experiencing more frequent and intense wildfires. The hotter and more often a stand of boreal forest catches fire, the deeper into the soil carbon pool the fire will burn, sending centuries-old carbon up in smoke in an instant. Logging of high-carbon primary forests is also a big issue in the boreal.

The number one protection for boreal forest carbon is reducing fossil fuel emissions. Only reversing climate change will bring boreal fires back to the historical levels these forests evolved with. In the meantime, active fire management in boreal forests offers a cost effective strategy to reduce emissions—studies found it could cost less than 13 dollars per ton of carbon dioxide emissions avoided. Strategies for fire management included both putting out fires that threaten large emissions, and controlled and cultural burning outside of the fire season to reduce the flammability of the landscape.