Each year at the Mountainfilm documentary film festival a mural is erected on a coffee shop in downtown Telluride, Colorado— a mountain mining town turned world-class winter sports destination. The festival showcases films with thought-provoking themes including environmental justice, Indigenous sovereignty, racial equity, and our collective responsibility to care for the natural world. These murals carry those themes year-round, becoming an integral part of Telluride’s main avenue and vibrant art culture. Past murals have been commissioned from artists including Shepard Fairey and Banksy.

This year, Woodwell’s lead cartographer Greg Fiske was selected to display his maps as art for the mural wall. The resulting piece, “Cartographies of Arctic Change”, will remain in place until next spring, and shows the rapidly changing Arctic landscape as seen by Fiske during the process of turning satellite imagery into data used by the Center’s climate scientists. Here, Fiske talks about his process and thinking behind the creation of this mural:

SR: How did this opportunity come about?

GF: It kind of came out of nowhere. I certainly wasn’t expecting it when they said, “we think your stuff would look great on this wall. What do you think?” And I said sure!

Of course, I’ve never created a map this size (26.5 by 36 feet), so I was eager to experiment. We had to go back and forth about which of the maps would best suit the space, yet also tell a story that leads viewers to our science here at Woodwell.

SR: How did you decide on the final image?

GF: I was told that whatever you put on the wall tends to influence the feeling that you get while you’re sitting there, having your coffee. [The shop owners] said that they made a mistake one year putting up an image of something cold like an iceberg, and it kind of made the whole place feel cold and dreary. So when we selected the maps, we had to make sure that they didn’t make people feel awkward while sitting there enjoying the outdoor space.

We came up with the idea of multiple maps in strips instead of one big map to be able to have each map show something different, but could all have a single theme and tell a story.

SR: What is that story?

GF: “Cartographies of Arctic Change”— it’s what we look at on a regular basis within our geospatial analyses, modeling, and science here at Woodwell that indicates rapid change in the Arctic.

Each one of these slices in the mural, in addition to being beautiful art, are also actually the data that goes into the models that drive Woodwell’s Arctic science.

The Arctic is one of the fastest changing landscapes on the planet— melting ice, thawing ground, lakes forming or draining, less snow and more fires— and you get a unique view of those changes when you spend so much time looking at geospatial data and satellite imagery.

I’m one of the people who pull in this raw data and prepare it for others who may be creating models or mapping some element of a landscape. I look at this data and make sure it’s the right format, quality, and resolution to satisfy the needs of models, but in doing so, there are many cases where I’m like, “Wow, this is really beautiful. Other folks should see the data at this stage, instead of just the final product.” So some of those images are what ended up in the mural. I hope it can give the many viewers who will see it a new perspective on the impacts climate change is having on one of the most beautiful regions of the world.

SR: What does it mean to you to have been selected to showcase that beauty through this mural?

GF: Of course it’s an honor. It’s interesting to think about something that I’ve seen so many times at screen size or social media size now being amplified to building size. I’m super thankful to the folks at Mountainfilm and Telco for displaying our work. I’ve never seen any of my maps in mural format and I won’t actually know how it’ll look until I get to Telluride and see it in person. I’m super excited!

From translating data into tools, to improving hazard management: Fund for Climate Solutions awards five new grants

The first round of 2025 Fund for Climate Solutions (FCS) awardees has been announced. The FCS advances innovative, solutions-oriented climate science through a competitive, internal, and cross-disciplinary funding process. Generous donor support has enabled us to raise more than $10 million towards the FCS, funding 74 research grants since 2018. Many of the latest cohort of grantees are translating data into tools for amplified impact. One project is bringing climate-related hazard expertise to at-risk communities, empowering them to co-create hazard management plans with their government officials.

A generic climate AI framework for multi-domain time series prediction

Lead: Dr. Yili Yang

Collaborators: Dr. Elchin Jafarov, Dr. Brendan Rogers, Dogukan Teber, Dr. José Lucas Safanelli, Dr. Andrea Castanho, Dr. Christopher Schwalm, Dominick Dusseau, Dr. Marcia Macedo, Dr. Jonathan Sanderman, Dr. Anna Liljedahl, Dr. Sue Natali, Dr. Michael Coe

Current climate science relies heavily on physics-based numerical models to make a wide range of predictions—from thawing permafrost in the Arctic, to tropical fires in the Brazilian Amazon, to soil carbon budgets of pastures, and risks associated with flooding. These types of models require an intense amount of computing power, and are expensive to run enough times to test a variety of detailed scenarios and assumptions. Researchers often need to simplify the models or the questions they are asking, limiting the insights that they can extract. To address this problem, the project team will use deep learning to develop a Center-wide AI framework for climate data that encompasses data from across regions and projects, reducing computational costs and energy demands. This new framework will have the potential to transform the ability of all Woodwell Climate researchers to provide policymakers with rapid, accurate predictions that support urgent climate response strategies.

Climate and Indigenous-centered boreal wildfire risk assessment

Lead: Dr. Kayla Mathes

Collaborators: Dr. Brendan Rogers and Dr. Peter Frumhoff

While fire has always been an important part of boreal ecosystems, fires that reach beyond historical patterns on the landscape are posing widespread consequences for climate, Indigenous sovereignty, and public health. Through our partnerships with land managers and community leaders in Alaska, Woodwell Climate researchers have identified two key barriers to responsive management and policy action: 1) Fire managers currently lack maps that identify areas with both a high probability of wildfire, and a high carbon emission potential from burning and permafrost thaw. 2) Current fire management priorities do not adequately include Indigenous knowledge and community needs. This project will generate two maps to address boreal fire management knowledge gaps. The team will create one map representing wildfire carbon vulnerability, and will also work with Yukon Flats Indigenous communities to co-produce a regionally-specific map that identifies their wildfire management needs and priorities.

Forms and functions of soil organic carbon

Lead: Dr. Jonathan Sanderman

Collaborators: Dr. José Lucas Safanelli, Dr. Ludmila Rattis, Dr. Christopher Neill

Not all carbon is created equal—some forms of carbon are easier for microbes to break down, while others are more persistent. In soils, scientists are typically interested in a few specific forms of organic carbon, but each type has a different decay rate. Measuring the amount of each type of carbon—referred to as fractions—in a soil sample is currently labor intensive, sometimes requiring highly specialized equipment. Woodwell Climate researchers recently proved that a 60-second, low-cost spectroscopy scan can provide similar information on soil carbon fractions to days of work with traditional methods. However, this scan relies on machine learning or deep learning algorithms and high-quality, geographically appropriate training datasets. This project will build an open-source database of soil carbon fraction data, along with freely-available models to predict soil carbon fractions using spectroscopy, hosted by the Woodwell-led Open Soil Spectral Library and Estimation Service. This groundbreaking solution offers a transformative approach to soil carbon monitoring—making soil carbon fraction prediction more widely accessible to labs around the world.

Empowering the Tropical Forests Forever Facility with a tool for informed decision-making

Lead: Dr. Glenn Bush

Collaborators: Kathleen Savage, Patrick Fedor, Emily Sturdivant, Dr. Wayne Walker, Dr. Ludmila Rattis, Dr. Michael Coe

The Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF), is an initiative spearheaded by the Government of Brazil to establish a US$125 billion global investment fund. If successfully established, TFFF can generate long-term finance to provide ongoing annual compensation to tropical forest nations to conserve intact tropical forests. The fund now needs to build confidence amongst potential sponsors to demonstrate feasible pathways to impact. The project team will create a new location-based dataset of cost-effective forest conservation options for the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Brazil, where Woodwell researchers have a long history of relationships and expertise. This dataset will provide valuable information around what forest conservation strategies will be effective, and where, based on financial and social benefits to people in the target landscapes. Ultimately, the team will be able to concretely identify how much forest conservation can be achieved with a given budget, and where to target efforts to resolve the highest-priority risks. With this information, the TFFF can demonstrate the effectiveness of the program and incentivize participation of sponsor countries and tropical forest nations.

Landslide hazard management workshops in Homer and Seward, Alaska

Lead: Dr. Anna Liljedahl

Collaborator: Dr. Jennifer Francis

Extreme rain events, glacier retreat, and permafrost thaw are making landslides and landslide-generated tsunamis in Alaska more likely. However, these hazards are not well-integrated into land and emergency management—for example, warning systems are relatively non-existent. The project team will host workshops in two Alaska communities at risk for landslides and landslide-generated tsunamis to raise awareness about the threats among residents and public agencies, and to identify landslide hazard management practices. The workshops will bring together experts in science and hazard mitigation; city, borough, and state officials; and community members to jointly develop recommendations for action. This effort builds on the ongoing work of Dr. Liljedahl’s project, Arctic Tsunamigenic Slope Instabilities Partnership (Arctic T-SLIP), and will support a future group of research proposals to the National Science Foundation on landslides and landslide-generated tsunami hazards. Insights gained from these workshops will also add detail to a Woodwell Climate Just Access risk report completed for Homer in 2021.

A map of Alaska created by Senior Geospatial Analyst Greg Fiske garnered two awards—the International Cartographic Association and International Map Industry Association Recognition of Excellence in Cartography, and Cartography Special Interest Group Excellence—at the Esri User Conference in San Diego this week.

Esri is the industry leader in mapping software and the Esri User Conference brought together more than 20,000 geospatial professionals including cartographers, software developers, students, end users, and policymakers. Woodwell Climate has an ongoing partnership with Esri and has attended the conference for more than two decades.

“These awards mean a great deal as the recognition comes from two very highly acknowledged cartographic organizations and the map pool at the Esri User Conference was immense,” Fiske said. “In the case of this map, not only did I share a basemap that we’re using widely in our Permafrost Pathways project, but I also shared a high-level overview of how I created the map and the resources (in the format of data, software, tutorials, and people) needed to do the same anywhere on the planet.”

The map that won the awards shows the topography of Alaska. To the average viewer, it is beautiful, informative, and not overly complicated. But Fiske also created a storymap that breaks down the data layers, and analytical and design steps required to create the map—and it is anything but simple.

Fiske has been creating maps at Woodwell Climate for more than 20 years, and is known among colleagues—at the Center and across the mapping community—for his analytical skill, creativity and artistry, and dedication to quality.

“People are drawn to a beautiful map,” Fiske said. “Putting our work on a map takes advantage of that scenario and gives us an opportunity to spotlight our research.”

Imagining Earth’s most probable futures

New climate education initiative portrays the warmer worlds we are likely to see this century, in hopes of preventing them

One point five—most readers will recognize that number as the generally accepted upper limit of permissible climate warming. With current temperatures already hovering at 1.1 degrees Celsius above the historical average, the race is on to hit that target, and the likelihood that we will surpass it is growing. Even if we do manage a 1.5 degree future, that’s still warmer than today’s world, which is already seeing devastating climate impacts.

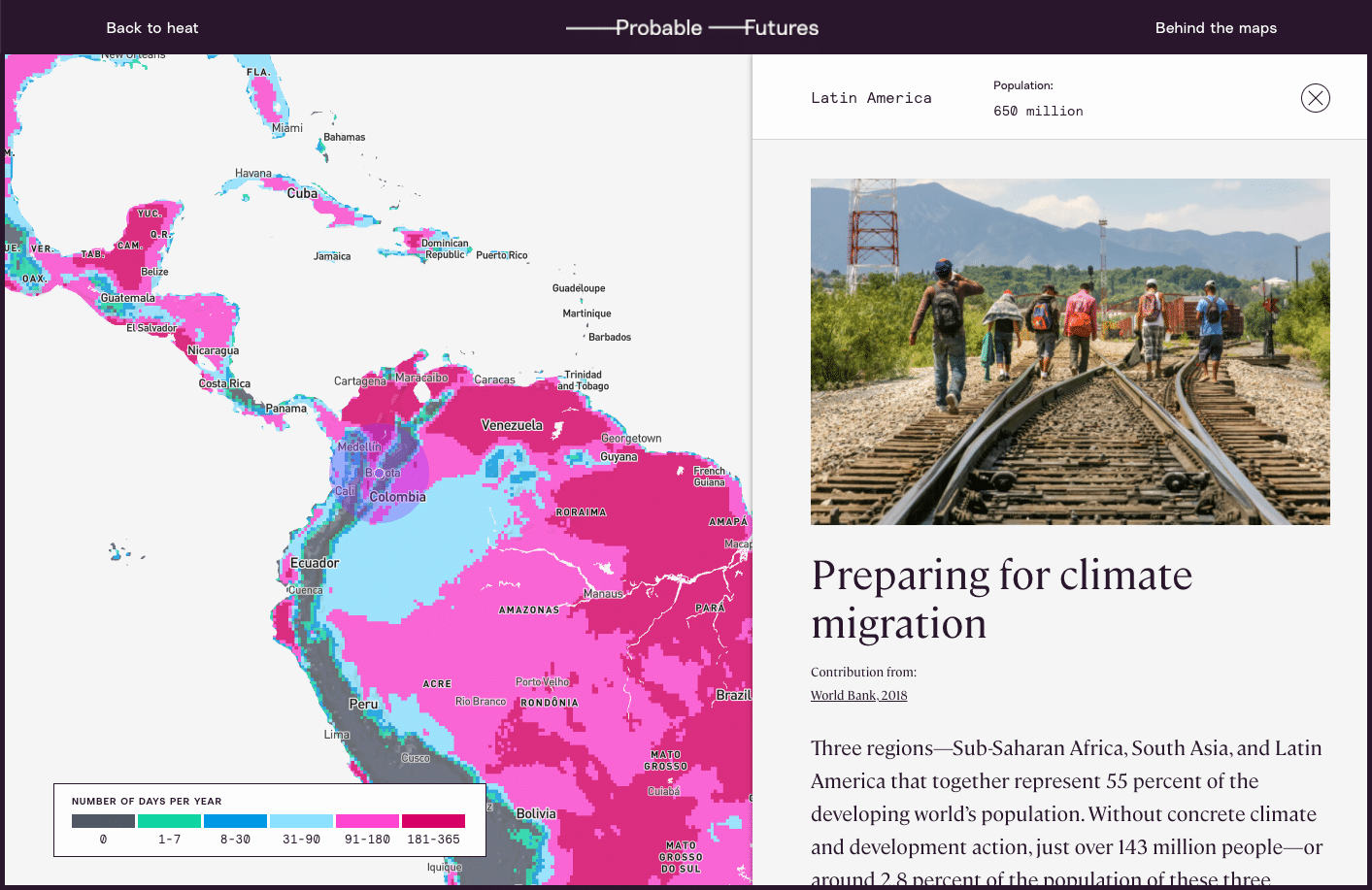

So what will it actually feel like to live in a 1.5 degree world—or a 2 degree one, or even 3? The Probable Futures initiative has built a tool to help everyone imagine.

Building a bridge between science and society

Probable Futures is a newly launched climate literacy initiative with the goal of reframing the way society thinks about climate change. The initiative was founded by Dr. Spencer Glendon, a senior fellow with Woodwell Climate who, after investigating climate change as Director of Research at Wellington Management, noticed a gap in need of bridging between climate scientists and, well… everyone else.

According to Dr. Glendon, although there was an abundance of available climate science, it wasn’t necessarily accessible to the people who needed to use it. The way scientists spoke about climate impacts didn’t connect with the way most businesses, governments, and communities thought about their operations. There was no easy way for individuals to pose questions of climate science and explore what the answers might mean for them.

In short, the public didn’t know what questions to ask and the technical world of climate modeling wasn’t really inviting audience participation. But it desperately needed to. Because tackling climate change requires everyone’s participation.

“The idea that climate change is somebody else’s job needs to go away,” Dr. Glendon says. “It isn’t anybody else’s job. It’s everybody’s job.”

So, working with scientists and communicators from Woodwell, Dr. Glendon devised Probable Futures—a website that would offer tools and resources to help the public understand climate change in a way that makes it meaningful to everybody. The site employs well-established models to map changing temperatures, precipitation levels, and drought through escalating potential warming scenarios. The data is coupled with accessible content on the fundamentals of climate science and examples of it playing out in today’s world.

According to the initiative’s Executive Director, Alison Smart, Probable Futures is designed to give individuals a gateway into climate science.

“No matter where one might be on their journey to understand climate change, we hope Probable Futures can serve as a trusted resource. This is where you can come to understand the big picture context and the physical limits of our planet, how those systems work, and how they will change as the planet warms,” Smart says.

Storytelling for the future

As the world awakens to the issue of climate change, there is a growing group of individuals who will need to better understand its impacts. Supply chain managers, for example, who are now tasked with figuring out how to get their companies to zero emissions. Or parents, trying to understand how to prepare their kids for the future. Probable Futures provides the tools and encouragement to help anyone ask good questions about climate science.

To that end, the site leans on storytelling that encourages visitors to imagine their lives in the context of a changing world. The maps display forecasts for 1.5, 2, 2.5, and 3 degrees of warming—our most probable futures, with nearly 3 degrees likely by the end of the century on our current trajectory. For the warming we have already surpassed, place-based stories of vulnerable human systems, threatened infrastructure, and disruptions to the natural world, give some sense of the impacts society is already feeling.

According to Isabelle Runde, a Research Assistant with Woodwell’s Risk Program who helped develop the maps and data visualizations for the Probable Futures site, encouraging imagination is what sets the initiative apart from other forms of climate communication.

“The imagination piece has been missing in communication between the scientific community and the broader public,” Runde says. “Probable Futures provides the framework for people to learn about climate change and enter that place [of imagination], while making it more personal.”

Glendon believes that good storytelling in science communication can have the same kind of impact as well-imagined speculative fiction, which has a history of providing glimpses of the future for society to react against. Glendon uses the example of George Orwell who, by imagining unsettling yet possible worlds, influenced debates around policy and culture for decades. The same could be true for climate communication.

“I’m not sure we need more science fiction about other worlds,” Glendon says. “We need fiction about the future of this world. We need an imaginative application of what we know.” Glendon hopes that the factual information on Probable Futures will spark speculative imaginings that could help push society away from a future we don’t want to see.

For Smart, imagining the future doesn’t mean only painting a picture of how the world could change for the worse. It can also mean sketching out the ways in which humans will react to and shape our new surroundings for the better.

“We acknowledge that there are constraints to how we can live on this planet, and imagining how we live within those constraints can be a really exciting thing,” Smart says. “We may find more community in those worlds. We may find less consumption but more satisfaction in those worlds. We may find more connection to human beings on the other side of the planet. And that’s what makes me the most hopeful.”