The critical missing expense in global climate budgets

A major emitter is being left out of the global climate budget, and Arctic communities are already feeling the impacts

A 2022 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report confirms that the Earth is on track to warm 1.5 degrees celsius by 2040. Warming beyond this will cause global issues like struggling coral reefs, catastrophic storms, and extreme heat waves. The international community has developed a global carbon budget that tracks how much carbon can be added to the atmosphere by human-caused emissions before we push warming past 1.5 and even 2 degrees. It functions much like a household budget— where spending more than you earn can jeopardize your stability and comfort.

With the carbon budget, that means balancing how much carbon is released into the atmosphere with how much is being stored by natural sinks. According to the IPCC, the world needs to wean itself off of “spending” down that budget as we rapidly approach 2 degrees of warming.

Permafrost is missing from the budget

But IPCC’s budget calculations aren’t factoring in a major source of emissions—permafrost thaw. Massive amounts of carbon are stored in frozen Arctic soils known as permafrost. As permafrost thaws, that carbon is released into the atmosphere in the form of carbon dioxide and methane. Scientists estimate that emissions from permafrost thaw will range from 30 to 150 billion tons this century.

Despite being on par with top-emitting countries like India or the United States, permafrost thaw is not included in the global carbon budget. It has historically been excluded because of gaps in data that make existing estimates of emissions less precise. Dr. Max Holmes, President of Woodwell Climate Research Center, says it’s “especially alarming… that permafrost carbon is largely ignored in current climate change models.” That’s because permafrost thaw emissions could take up 25-40% of our remaining emissions budgeted to cap warming at 2°C. Imagine leaving the cost of rent out of your household budget. It doesn’t mean you don’t have to pay it, it just means you won’t be prepared when that bill arrives.

Excluding permafrost thaw also means that projections of the rate of warming will be off. The unaccounted carbon will speed up warming, reducing the amount of time we have to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

Permafrost thaw is already negatively impacting Arctic residents, especially Indigenous communities. In 2019, a Yup’ik community that has lived in Newtok, Alaska for hundreds of years had to begin moving to higher, volcanic ground because the thawing permafrost under their town was causing disastrous floods and sinking infrastructure. Woodwell Arctic program director and senior scientist, Dr. Sue Natali, who studies permafrost thaw in Yup’ik territory, says “it’s a place where permafrost is on the brink of thawing, and will be thawed by the end of the century, if not much sooner.”

Since permafrost spans multiple countries, it has been difficult to determine who should take responsibility for it. Consequently, there is currently little government framework for adaptation. The Yup’ik people had to reach out to a variety of government agencies and lived without plumbing for decades before the federal government finally awarded them support for relocation. The community paid a heavy price for it, though. Without proper policy in place to manage climate relocation, they had to bargain for government assistance, and in the end, turned ownership of the land they were leaving over to the U.S. government.

It took sixteen years from when Congress agreed to assist the Yup’ik community to when their promises were put into action. While scientists, like the ones spearheading Woodwell’s Permafrost Pathways program, are monitoring and modeling thaw to better prepare people for the damage it can cause, vulnerable communities do not have sixteen years to wait for assistance and relocation.

If permafrost thaw continues to be overlooked by government agencies, then it will remain difficult to prevent the Earth from warming beyond 2ºC and to support frontline communities most affected by it. Tackling permafrost thaw for both Arctic communities and the planet will require a coordinated international effort.

Looking for some background on Permafrost? Read the first piece in our permafrost series: “What is Permafrost?” To learn about what must be done to combat this issue, read part three: “What can be done about permafrost thaw?”

What is permafrost?

Centuries-old frozen soil is under threat from rapid warming

Thinking about climate change usually brings to mind dramatically melting ice caps and rising sea levels, but there’s another threat that’s caught the attention of climate scientists for its potential to be equally as disastrous—thawing permafrost.

Located anywhere between a few centimeters to 4,900ft below the Earth’s surface, permafrost is soil composed of sand, gravel, organic matter, and ice that has been frozen for at least two consecutive years. Some has been frozen for centuries or even millenia, and it’s this ancient permafrost in the Arctic that holds the greatest significance for climate change.

Arctic permafrost stretches across Alaska, Scandinavia, Russia, Iceland, and Canada, and can be found beneath the Arctic Ocean, the Arctic tundra, alpine forests, and boreal forests. It covers 15% of the land in the Northern Hemisphere and 3.6 million people live atop it. Scientists estimate that Arctic permafrost contains 1.4 trillion tonnes of carbon, an amount more than double what is currently in the Earth’s atmosphere. That carbon sink is stable as long as it stays frozen, but when it thaws, soil microbes break down the organic matter in permafrost and release carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere, increasing the rate of climate change.

In many places, forests, plants, and peat act as protective insulation for Arctic permafrost. This insulation helps keep carbon-storing organic matter, like plants and animals, as well as bacteria and archaea, frozen in the permafrost. However, climate change is already causing the Arctic to warm three to four times faster than the rest of the planet.

In addition to rapid warming speeding decay, it also strips back permafrost’s protective layers with increasing fires and heavy summer rains that burn and erode away top soil layers, further accelerating thaw. In some places, permafrost thaws so abruptly that the ground can collapse. Developing infrastructure that requires deforestation and underground pipes further exposes permafrost to warming. Additionally, as sea ice melts, coastal Arctic permafrost is exposed to warmer waters. The combined result is extensive permafrost thaw across the region.

Researchers have been studying permafrost thaw to determine the size of the threat it poses. Methods such as placing soil moisture sensors in strategic locations and examining soil cores collected by drilling holes into the soil to document the different layers of permafrost help gauge the rate and extent of thaw.

In a recent TEDTalk, Dr. Sue Natali, Woodwell’s Arctic program director and senior scientist, cautioned that, “By the end of this century, greenhouse gas emissions from thawing permafrost may be on par with some of the world’s leading greenhouse-gas-emitting nations.”

There are already visible signs of vast permafrost thaw in the Arctic. Since ice is an essential part of the ground’s structural integrity, the soil becomes unstable when it thaws. This leads to dangerous situations like landslides, sinkholes, and destabilized infrastructure that threaten millions of people. Remote communities are particularly impacted, losing access to roads and sources of freshwater.

For both the carbon it threatens to release, and the destabilizing impacts it has on Arctic residents, permafrost thaw is a serious threat. One that, as the Arctic continues to warm, demands urgent attention and remediation.

Until now, that attention has been slow in coming. Read about why combatting permafrost thaw is such a complex issue in part two of our Permafrost series: “The critical missing expense in global climate budgets.”

It was supposed to be a quiet season, but only two months into summer and Alaska is already on track for another record-setting wildfire season. With 3 million acres already scorched and over 260 active fires, 2022 is settling in behind 2015 and 2004 so far as one of the state’s worst fire seasons on record. Here’s what to know about Alaska’s summer fires:

2. Historic fires are Burning in Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta and Bristol Bay

Southwestern Alaska, in particular, has been suffering. The season kicked off with an unseasonably early fire near Kwethluk that started in April. Currently, the East Fork Fire, which is burning near the Yup’ik village of St. Mary’s, AK, is among the biggest tundra fires in Alaska’s history. Just above Bristol Bay, the Lime Complex— consisting of 18 individual fires— has burned through nearly 865,000 acres. One of the longest lasting fires in the Lime Complex, the Upper Talarik fire, is burning close to the site of the controversial open-pit Pebble Mine.

2. Seasonal predictions showed a low-fire season

For Dr. Brendan Rogers, who was in Fairbanks, AK for a research trip in May, the explosive start of the fire season contrasts strongly to conditions he saw in late spring.

“It was a relatively average spring in interior Alaska, with higher-than-normal snowpack. Walking around the forest was challenging because of remaining snow, slush, and flooded trails,” said Dr. Rogers.

Early predictions showed a 2022 season low in fire due to heavy winter snow. But the weather shifted in the last ten days of May and early June. June temperatures in Anchorage were the second highest ever recorded. High heat and low humidity rapidly dried out vegetation and groundcover, creating a tinderbox of available fuel. This sudden flip from wet to dry unfolded similarly to conditions in 2004, which resulted in the state’s worst fire season on record.

3. Climate Change is accelerating fire feedback loops

The conditions for this wildfire season were facilitated by climate change, and the emissions that result from them will fuel further warming. The hot temperatures responsible for drying out the Alaskan landscape were brought on by a persistent high pressure system that prevents the formation of clouds— a weather pattern linked to warming-related fluctuations in the jet stream.

“With climate change, we tend to get more of these persistent ridges and troughs in the jet stream,” says Dr. Rogers. “This will cause a high pressure system like this one to just sit over an area. There is no rain; it dries everything out, warms everything up.”

The compounding effects of earlier snowmelt and declining precipitation have also made it easier for ground cover to dry out rapidly under a spell of hot weather. More frequent fires also burn through ground cover protecting permafrost, accelerating thaw that releases more carbon. According to the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy, the frequency of big fire seasons like this one are only increasing— a trend expected to continue apace with further climate change.

Additionally, this summer has been high in lightning strikes, which were linked to the ignition of most of the fires currently burning in Alaska. Higher temperatures result in more energy in the atmosphere, which increases the likelihood of lightning strikes. On just one day in July over 7,180 lightning strikes were reported in Alaska and neighboring portions of Canada.

4. Communities are Being Affected Hundreds of Miles Away

The destruction from these wildfires has forced rural and city residents alike to evacuate and escape the path of burning. Some residents of St. Mary’s, AK have elected to stay long enough to help combat the fires, clearing brush around structures and cutting trees that could spread fire to town buildings if they alight.

But the impact of the fires is also being felt in towns not in the direct path of the flames. Smoke particulates at levels high enough to cause dangerously unhealthy air quality were carried as far north as Nome, AK on the Seward Peninsula.

“Even though a lot of these fires are remote, that doesn’t preclude direct human harm,” says Woodwell senior science policy advisor Dr. Peter Frumhoff.

Recent research has shown that combatting boreal forest fires, even remote ones, can be a cost effective way to prevent both these immediate health risks, as well as the dangers of ground subsidence, erosion, and loss of traditional ways of life posed by climate change in the region.

5. The season is not over yet

Mid-July rains have begun to slow the progression of active fires but, according to Dr. Frumhoff, despite the lull, it is important to keep in mind that the season is not over yet.

“The uncertainty of those early predictions also applies to the remainder of the fire season — we don’t know how much more fire we’ll see in Alaska over the next several weeks.”

Woodwell launches new project monitoring, combatting the effects of permafrost thaw

A $41 Million grant through The Audacious Project will fund Permafrost Pathways work

It’s a big idea—a pan-Arctic monitoring network for permafrost emissions—but big ideas are exactly what The Audacious Project was created to foster.

This April, Woodwell Climate Research Center was awarded 41.2 million dollars through Audacious to not only build such a network, filling gaps in our understanding of how much carbon is released into the atmosphere from thawing permafrost, but also to put research to work shaping policy and helping people.

The new project, called Permafrost Pathways, combines scientific prowess from Woodwell with policy, community engagement, and Indigenous knowledge from the Arctic Initiative at Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, the Alaska Institute for Justice (AIJ), and the Alaska Native Science Commission.

Carbon emissions from permafrost thaw are one of the biggest areas of uncertainty in global climate calculations. Thawing permafrost is expected to release between 30 and 150 billion tons of carbon by 2100, the higher estimates on par with or even exceeding the United States’ cumulative emissions if allowed to continue at current rates. Yet permafrost is not accounted for in carbon budgets and international agreements. Permafrost Pathways will develop more complete data on permafrost carbon and deliver that research into the hands of those poised to decide how we deal with the warming Arctic.

Big problems require big solutions

Permafrost Pathways is led on the Woodwell side by Arctic Program Director Dr. Sue Natali and Associate Scientist Dr. Brendan Rogers, who have both been researching permafrost carbon for years. Dr. Natali found her way to the Arctic through a desire to work in a place significant to the global carbon story. The rapid changes she has witnessed in the past decade have underscored the Arctic as ground zero for climate change.

“I’ve seen dramatic changes from one year to the next in the places where I work, and Arctic residents have been observing these changes for decades,” Dr. Natali says. “You can measure something one year and then the ground there collapses the next. The physical changes across the landscape are really startling to see.”

Drs. Natali and Rogers have seen eroded hillslopes, research trips abandoned due to wildfire, community meetings with Arctic residents whose homes are sinking—every experience reinforced the fact that there was still much more to learn about how thawing permafrost feeds into climate change and is impacting Arctic communities.

The Audacious grant will allow Drs. Natali and Rogers to pull together the threads of their prior research into a project that starts to tackle the issue on a grander scale.

“When you’re focused on individual problems or hypotheses, you’re not able to really think big about something like monitoring across the Arctic,” says Dr. Rogers. “Opening up a funding source like this lets you think at a scale that matches the problems we face.”

The project is thinking really big, with the goal of installing 10 new eddy covariance towers—structures with instruments that measure carbon flux—in key areas where data is currently lacking. Pathways will also maintain existing key towers that would otherwise be decommissioned, and augment others to measure carbon fluxes year-round.

“There are a lot of existing towers that are either not running through the winter, or they’re not measuring methane, or they’re on hold for instrumentation upgrades or lack of funding,” Dr. Natali says. “We will get even more new data by maintaining old towers than constructing new ones.”

In parallel, Woodwell will work with a team at University of Alaska Fairbanks to develop a novel permafrost model that fully harnesses the data, accounting for important but currently neglected processes, and ultimately delivers more accurate projections of permafrost emissions to inform policy makers and Arctic communities.

‘It’s an awful decision’

While the science team ramps up new data collection, AIJ will be breaking down the issue of adaptation. The Arctic is warming faster than anywhere else on Earth, and it is not waiting for exact measurements to make the consequences known.

The land upon which many Alaska Native communities are located is destabilizing in the face of usteq—a Yupik word for the catastrophic ground collapse that occurs when thawing permafrost, erosion, and flooding combine to pull the ground out from under them. In many places the formerly solid cornerstones of villages—houses, roads, airports, cemeteries— have had to be picked up and moved to more stable ground.

“It is an awful, awful decision that communities are being faced with because the land on which they’re living is becoming uninhabitable,” says Executive Director of AIJ, Dr. Robin Bronen.

On top of the trauma of watching their villages sink into the Earth, there is no clear path for Arctic communities deciding they must completely relocate.

“It’s become painfully clear that we in the United States have no institutional or governance structure to facilitate this type of movement of people,” says Dr. Bronen. There is no standardized way for people displaced by the climate crisis seeking resettlement to apply for funding and technical assistance for a community-wide relocation.

“If policy changes aren’t made nationally, then a lot of communities in the United States are going to be experiencing this incredible disconnect between making the decision that they are ready to leave, but having no resources to implement that decision,” says Dr. Bronen.

Permafrost Pathways will be working with Arctic residents to help them adapt to their rapidly shifting landscape. Through AIJ and the Alaska Native Science Commission, the project will connect with communities, collaborate to generate data they can use in their decision making and, if they make the choice to move, work with them to secure the resources needed for relocation.

Factoring Permafrost Thaw into our Global Future

Permafrost Pathways isn’t the first to tackle these issues but, Dr. Natali says, it does represent a unique combination of expertise that could push forward both carbon mitigation and climate adaptation policies.

Leader of the Arctic Initiative, professor, and Senior Advisor to Woodwell’s president, Dr. John Holdren understands the value of connections in making lasting change; he has been speaking to top policy makers in the U.S. and abroad for much of his career.

“All of us at the Belfer Center have been linking science and policy for a long time and communication is important to that,” says Dr. Holdren. “In my view, it’s going to remain important to have personal connections at high levels.”

Working through these connections, Permafrost Pathways will put the project’s science into the hands of policymakers to impress upon them the issue’s urgency.

“All the news coming out about permafrost carbon has been bad news,” says Dr. Holdren. “I think what we are going to find is that the high estimates are much more likely to be right than the low estimates. We’ve got to get that factored into the policy process.”

For Dr. Natali, the most important outcome of Permafrost Pathways is a future in which the threats presented by permafrost thaw are taken seriously by governments.

“I want to see permafrost thaw emissions accounted for,” says Dr. Natali. “I want to see the national and international community actually wrestle with the effects of permafrost thaw and to take action to respond to the climate hazards.”

Dr. Rogers says he hopes the collaborative nature of this already-big project will have even larger, rippling effects— paving the way for new partnerships and policy change.

“There’s the critical work that we will be doing, and then there are the new doors that a project of this scope opens,” says Dr. Rogers. “And we aren’t reaching our end goal without those open doors.”

The Audacious Project is an initiative of the non-profit TED that funds large-scale solutions to the world’s most challenging problems. Every year, the Project selects a cohort of big ideas to nurture with funding and resources.

Tune in to PBS NOVA on February 2 to watch Arctic Sinkholes, an original documentary that explores the hidden dynamics of thawing permafrost and the emissions it releases. The documentary features Woodwell Arctic Program Director, Dr. Sue Natali, alongside other prominent climate scientists working to better understand how climate change is impacting the Arctic.

The film centers on the 2014 discovery of methane craters in the Arctic. These features of the landscape are formed as permafrost thaws, and trapped greenhouse gasses expand, pushing the soil up. When the pressure becomes too great, these bubbles of earth can explode suddenly, creating massive craters on the Arctic landscape and releasing a burst of atmosphere-warming gasses.

“There’s a lot of discussion about carbon dioxide and its relationship to climate, but the impact of

methane coming out of the Arctic is potentially enormous,” says NOVA Co-Executive Producer Julia Cort. “Making accurate predictions about the future depends on good data, and Arctic Sinkholes reveals what scientists have to do to get that data, as they try to measure an invisible, odorless gas that’s underground in some of the most remote and challenging environments in the world.”

To better understand the extent and significance of these craters, Dr. Natali and Woodwell Senior Geospatial Analyst, Greg Fiske, devised a method of mining satellite imagery data for key characteristics that would indicate a recent explosion. A sudden shift from vegetation to water, for example — often, craters quickly fill up with rain, becoming lakes that obscure their own origins.

Outgassing from the craters themselves represents only a small subset of the larger potential emissions from permafrost thaw. Current estimates show that thawing permafrost could contribute as much to warming this century as continued annual emissions from the United States.

Methane craters make evident the speed at which the Arctic is warming, and the changes permafrost thaw is causing on the landscape. In their research, Dr. Natali and Fiske uncovered other impacts of permafrost thaw— slumping ground, sinkholes, and coastal erosion are destabilizing the ground on which many Arctic communities are built.

“These abrupt changes that are occurring in this once-frozen ground are happening faster than we expected,” said Dr. Natali. “And that is not only going to accelerate warming, but also affect the lives of millions who make their home in the Arctic.”

Future research will work towards more precise estimates of permafrost thaw emissions and a better understanding of the changing Arctic.

Arctic Sinkholes premieres Wednesday, February 2, 2022 at 9pm ET/8C on PBS and will be available for streaming online at pbs.org/nova and on the PBS video app.

Arctic communities and infrastructure under threat from thawing permafrost

The Arctic has warmed twice as fast as the rest of the globe in the last two decades. In this region where the ground in some places is literally made of ice, rapid warming poses a serious threat to the lives, livelihoods and infrastructure of Arctic communities. A new review led by Dr. Gabriel Wolken from the University of Alaska, Fairbanks and Woodwell Associate Scientist Dr. Anna Liljedahl details the biggest hazards that could result—and in some cases already have—from permafrost and glacial thaw.

The paper was released as a special addition to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Arctic Report Card, an annual report on the status of the Arctic region. In it, the authors outline what we know, and the much larger gaps in our knowledge, about how thawing permafrost and melting glaciers are impacting Arctic communities.

Ice holds the Arctic together. An estimated 23 million square miles of land in the Northern hemisphere is permafrost, soil that traditionally stayed frozen solid year-round. When it begins to thaw, the land slumps, which can cause sinkholes, erosions, and landslides. Retreating glaciers can also destabilize mountain slopes. When collapsing glaciers or mountainsides fall into a nearby water body, they can set off a chain of cascading hazards, including outburst floods, debris flow, and even tsunamis.

Events like these have already been documented, with serious impacts on Arctic residents, yet research and monitoring of these hazards have been lacking.

“Houses are already collapsing, communities are already being impacted by permafrost thaw and having to adapt, including in some cases, to relocate. That’s been happening for a decade, at least, and it’s not getting the attention it should be,” says Woodwell Arctic Program Director Dr. Sue Natali, who also contributed to the Report Card.

And there is vast potential for unstable Arctic ground to have far-reaching global impacts. The collapse of an oil tank in Norilsk, Russia was partly attributed to the extremely warm conditions of 2020. Roads, pipelines, and shipping lanes are all at risk from thaw-related hazards.

“It’s not only affecting someone living near a glacier or on permafrost, it also extends farther than that,” Dr. Liljedahl says. “It includes national security. And we do not have broad-scale hazard identification and detection across the Arctic, or near real-time tracking of permafrost thaw and unstable slopes. We can do a lot more in utilizing the vast amounts of remote sensing imagery and observations made by people living in permafrost and glacier-affected landscapes.”

What’s desperately needed, Dr. Liljedahl says, are early warning systems that can alert residents of imminent threats, especially ones designed in tandem with the communities being affected. But, without more research and widespread monitoring of permafrost and unstable slopes, building such a system would be nearly impossible—akin to taking precautions against a volcanic eruption without knowing where the volcano is.

The behavior and rate of thaw is also likely to change as climate change progresses. Permafrost itself releases emissions when it thaws and that accelerates the warming process, increasing the urgency for the necessary systems to be put into place.

“The rate of hazard formation and the combined effects of these hazards is much higher than it has been in the past, which will make it more challenging to respond to without accelerated efforts to monitor and map these hazards, and develop cohesive response plans,” says Dr. Natali.

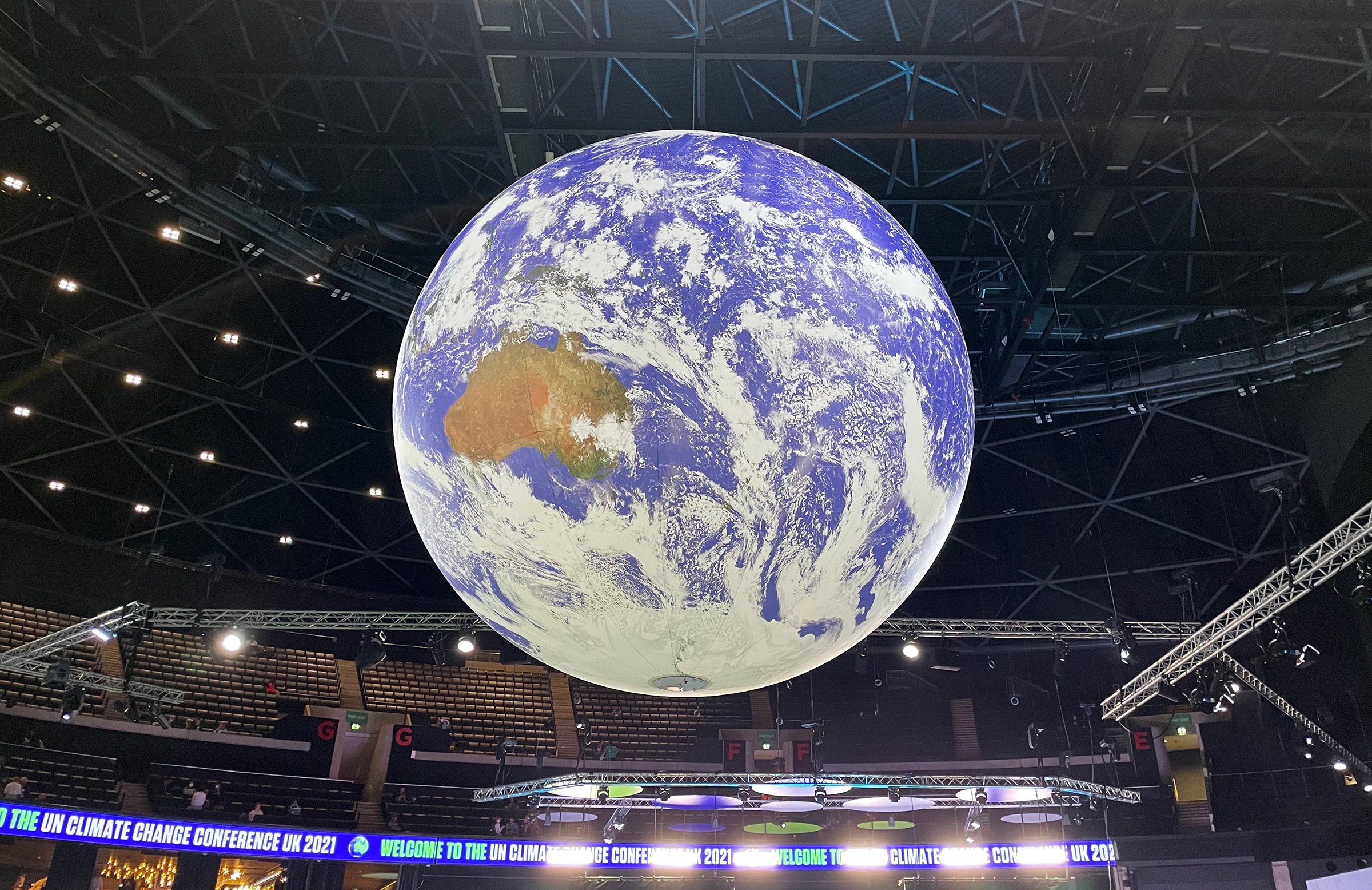

Success or failure? Woodwell scientists deem COP26 a mixed bag

Glasgow Climate Pact alone is not enough to limit warming to 1.5 C, but COP26 made real progress

For the first two weeks of November, diplomats and scientists from around the world descended on Glasgow, Scotland for the United Nations’ 26th annual Conference of Parties—hailed by some as the “last, best, hope” for successful international cooperation on the issue of climate change. Woodwell sent three expert teams to push for more ambitious policies that integrate our understanding of permafrost thaw and socioeconomic risks, and for financial mechanisms to scale natural climate solutions. Here are their thoughts on the successes and failures of this pivotal meeting.

Bold pledges but uncertain follow-through for tropical forests

The conference started off with a bold promise from 100 nations to end deforestation by 2030, accompanied by a pledge of more than $19 billion from both governments and the private sector. Though similar pledges to end deforestation have failed in the past, the funding pledged alongside this one gives reason to be hopeful.

$1.7 billion of the funds are allocated specifically to support Indigenous communities, which Woodwell Assistant Scientist Dr. Glenn Bush believes is a big step forward, though creating policies that are equally supportive will be where the real work gets done.

“It’s particularly welcome that Indigenous peoples are finally being acknowledged as key protectors of forests. The real challenge, however, is how to deliver interlocking policies and actions that really do drive down deforestation globally and scale up nature-based solutions to climate change.”

Dr. Ane Alencar, Director of Science at IPAM Amazônia, said that, for Brazil, half of the solution could come from enforcing existing laws and designating public forests. The other half could come from consolidating protected areas, creating incentives for private land conservation, and providing technical support for sustainable food production.

Dr. Bush also presented the CONSERV project, a joint initiative between IPAM and Woodwell that provides compensation for farmers who preserve forests on their land, above and beyond their legal conservation requirements. Increasing the scale and financing of viable carbon market plans like CONSERV could be crucial in incentivizing greater forest protection.

Climate risk a growing focus for governments

During the second week of the conference, Woodwell released a summary report on a series of climate risk workshops with policymakers and climate risk experts from 13 G20 nations. These workshops, conducted in collaboration with the COP26 Presidency and the British government’s Science and Innovation Network, identified challenges to incorporating climate risk assessments into national-level policy, and the report made recommendations for moving from simply making the science available to making it useful for implementation. The report demonstrated a desire from policymakers to get involved in climate risk analyses early in the process, to ensure the information addresses a country’s particular needs.

One success of the conference was the creation of a new climate risk coalition, led by Woodwell. The coalition, composed of 9 other organizations, will produce an annual climate risk assessment for policymakers.

“Understanding the full picture of climate risk is incredibly important when you’re setting policy,” explained Woodwell’s Chief of External Affairs, Dave McGlinchey. “We also heard, however, that the climate risk assessments need to be designed with the policymakers who will eventually use them. This research must speak directly to their interests if it is going to be delivered effectively.”

The increased desire of policymakers to better understand and address oncoming climate risks demonstrates an important shift to viewing climate change as a present problem, rather than solely a future one.

Permafrost thaw presents the greatest remaining uncertainty in forecasting emissions

One risk that still isn’t high enough on the COP agenda is rapid Arctic change, particularly permafrost thaw. The Cryosphere Pavilion, hosted by the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative, convened conversations ranging from the implications of permafrost thaw, to environmental justice for Northern Communities and respecting Indigenous knowledge and culture. For Arctic Program Director, Dr. Sue Natali, the Indigenous-led panels were some of the most impactful of the conference. But postdoctoral researcher Dr. Rachael Treharne noted that, no matter how well attended, there’s a difference between being in the Cryosphere Pavilion and being on the main stage.

Woodwell was among a group of organizations pushing to get permafrost emissions the attention it demands. Emissions released by thawing permafrost are currently not accounted for in national commitments, but are potentially equivalent to top emitting countries like the U.S. November 4 at the conference was “Permafrost Day” and each event was at full capacity for the pavilion, signaling growing attention to permafrost science. Woodwell, alongside a dozen polar and mountain interest groups called for even more commitment to the cryosphere conversation at the upcoming Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice U.N. climate conference in Bonn scheduled for June of 2022.

Even with this greater recognition of the seriousness of Arctic climate change, the region and its people are being hit much harder and faster than the rest of the globe. Slow-moving decision-making and talk without follow-through will seriously endanger Arctic residents.

“I left the COP having a very hard time feeling ‘optimistic’, while knowing that the hazards of climate change are already severely impacting Arctic lands, cultural resources, food and water security, infrastructure, homes, and ways of living,” said Dr. Natali. “After repeated years of record-breaking Arctic wildfires, heatwaves, and ice loss, I’m not sure how a 1.5 or 2C warmer world—one in which we know that these events will only get worse—is a reasonable goal.”

Though missing necessary milestones at COP26, climate action is accelerating

Overall, however, the final Glasgow Climate Pact fell short of the ambitious action the world needs in order to limit warming. The deal made several last-minute compromises surrounding the phase out of fossil fuels. COP president Alok Sharma said that, while a future with only 1.5 degrees of warming is possible, it is fragile—dependent on countries keeping to their promises.

Despite this, McGlinchey says there was real progress at COP26. The conference reached a resolution that earned the unanimous agreement of all attending parties. The formal process has also begun to accelerate, with nations required to return with more ambitious climate mitigation plans next year, rather than on the previous five year timeline.

“We are not yet where we need to be,” McGlinchey said. “But we are better off than where we were two weeks ago. Let’s keep going.”

Black spruce are losing their legacy to fire

Although evolved to thrive in fire-disturbed environments, a recent study shows more frequent fires are threatening black spruce resilience

For the past five to ten thousand years, black spruce have been as constant on the boreal landscape as the mountains themselves. But that constancy is changing as the climate warms.

A recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, led by Dr. Jennifer Baltzer, Canada Research Chair in Forests and Global Change at Wilfrid Laurier University, found that shifts in wildfire regimes are pushing black spruce forests to a tipping point, beyond which the iconic species may lose its place of dominance in boreal North America.

Synthesizing data from over 1500 fire-disturbed sites, the study showed black spruce’s ability to regenerate after fire dropped at 38% of sites and failed completely 18% of the time—numbers never before seen in a species evolved to thrive after fire.

The Stabilizing Feedback of Black Spruce

“They almost look like a Dr. Seuss tree.” says Dr. Brendan Rogers, an Associate Scientist at Woodwell and co-author on the PNAS study. He’s referring to the way black spruce are shaped—short branches that droop out of spindly trunks. Clusters of small dark purple cones cling to the very tops of the trees. Black spruce forests tend to be cool and shaded by the dense branches, and the forest floor is soft and springy.

“The experience of walking through these forests is very different from what most people are accustomed to. The forest floor is spongy, like a pillow or waterbed,” Dr. Rogers says. “It’s often very damp, too, because black spruce forests facilitate the growth of moss and lichen that retain moisture.”

However, these ground covers can also dry out quickly. Spruce have evolved alongside that moss and lichen to create a fire-prone environment. It only takes a few days or even hours of hot and dry weather for the porous mosses to lose their moisture, and the spruce are full of flammable branches and resin that fuel flames up into the tree’s crown.

Black spruce need these fires to regenerate. Their cones open up in the heat and drop seeds onto the charred organic soil, which favors black spruce seedlings over other species. The organic soil layers built up by the moss are thick enough to present a challenge for most seedlings trying to put down roots, but black spruce seeds are uniquely designed to succeed.

Dr. Jill Johnstone, Affiliate Research Scientist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, who also contributed to the PNAS study, compares it to a lottery system that black spruce have rigged for millennia.

“After fire, anything can happen,” says Johnstone. “But one way to make sure you win the lottery is to buy a lot of tickets. Black spruce has the most tickets. It has the most number of seeds that are the right size to get roots down into mineral soil, and so it tends to regenerate after fire.”

Potential competitors like white spruce, Dr. Johnstone says, don’t disperse very far from standing trees so they only get a few lottery tickets. Deciduous species like aspen or birch have seeds that are too small to work through the thick organic layers—their tickets are faulty. So the fire lottery tends to perpetuate black spruce’s dominance in what’s known as a “stabilizing feedback loop”.

Hotter, Dryer Conditions are Inhibiting Black Spruce Regeneration

That stable loop has begun to break down, however. Black spruce just aren’t re-establishing themselves as frequently after fire. The study examined the characteristics of different sites to better understand what might be hampering regeneration success.

Sites that failed to regenerate with black spruce were typically drier than normal. They also tended to have shorter intervals between successive fires. Black spruce stands have historically experienced the kinds of intense, stand-replacing fires that burn through everything only once per century. This long interval allows the trees to build up a healthy bank of cones to release seeds the next time they burn. More frequent, returning fires short-circuit the regeneration process.

Increased burning also strips away more of that thick organic soil layer that favors black spruce, revealing mineral soils underneath that level the playing field for other tree species. The more completely combusted those organic layers are, the more likely spruce are to have competition from jack pine, aspen, or birch. Loss of black spruce resilience was more common in Western North America, which aligns with the fact that drier sites are more likely to lose their black spruce.

“Basically, the drier the system is, the more vulnerable it is to fire,” Dr. Baltzer says. “And these are the parts of the landscape that are also more likely to change in terms of forest composition, or shift to a non-forested state after fire. If climate change is pushing these systems to an ever drier state, these tipping points are more likely to be reached.”

For Dr. Rogers, it also highlights the real possibility of losing black spruce across much of boreal North America as the region warms.

“This is evidence that black spruce is losing its dominant grip on boreal North America,” Rogers says. “It’s happening now and it’s probably going to get worse.”

Losing Black Spruce Could Accelerate Permafrost Thaw

Landscape-wide ecological shifts from black spruce to other species will have complicated, rippling impacts on the region.

Of most concern is the impact on permafrost. In many parts of the boreal, those mossy soil layers that promote black spruce also insulate permafrost, which stores large amounts of ancient carbon. Replacing the dark, shaded understory of a black spruce forest with a more open deciduous habitat that lacks mossy insulation could accelerate thaw. Thawing permafrost and associated emissions would accelerate a warming feedback loop that could push black spruce to its tipping point.

Widespread loss of black spruce also has implications for biodiversity, particularly caribou species that overwinter in the forest and feed on lichen. Both barren-ground and boreal caribou, important cultural species for northern communities, are already in decline across the continent and would suffer more losses if the ecosystem shifts away from the black spruce-lichen forests that provide food and refuge.

Dr. Johnstone did point out some potential for black spruce to recover, even if initial regeneration post-fire is dominated by other species. Slower growing, but longer lived, conifers can often grow in the shade of pioneer deciduous species and take over when they begin to die off—but this requires longer intervals between fires for the spruce to reach maturity. There is also the possibility that more deciduous trees, which are naturally less flammable than conifers, could help plateau increasing fires on the landscape.

But both these hopes, Dr. Baltzer says, are dependent on getting warming into check, because deciduous or conifer, “if it’s hot enough, and the fuel is dry enough, it will burn.”