What to know about Alaska’s historic fire season

Looking forward to a respite year, Alaska instead faces one of its worst fire seasons on record

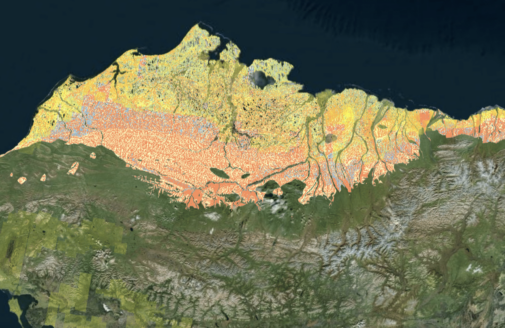

Fire smoke from the East Fork Fire.

photo by BLM Alaska Forest Service

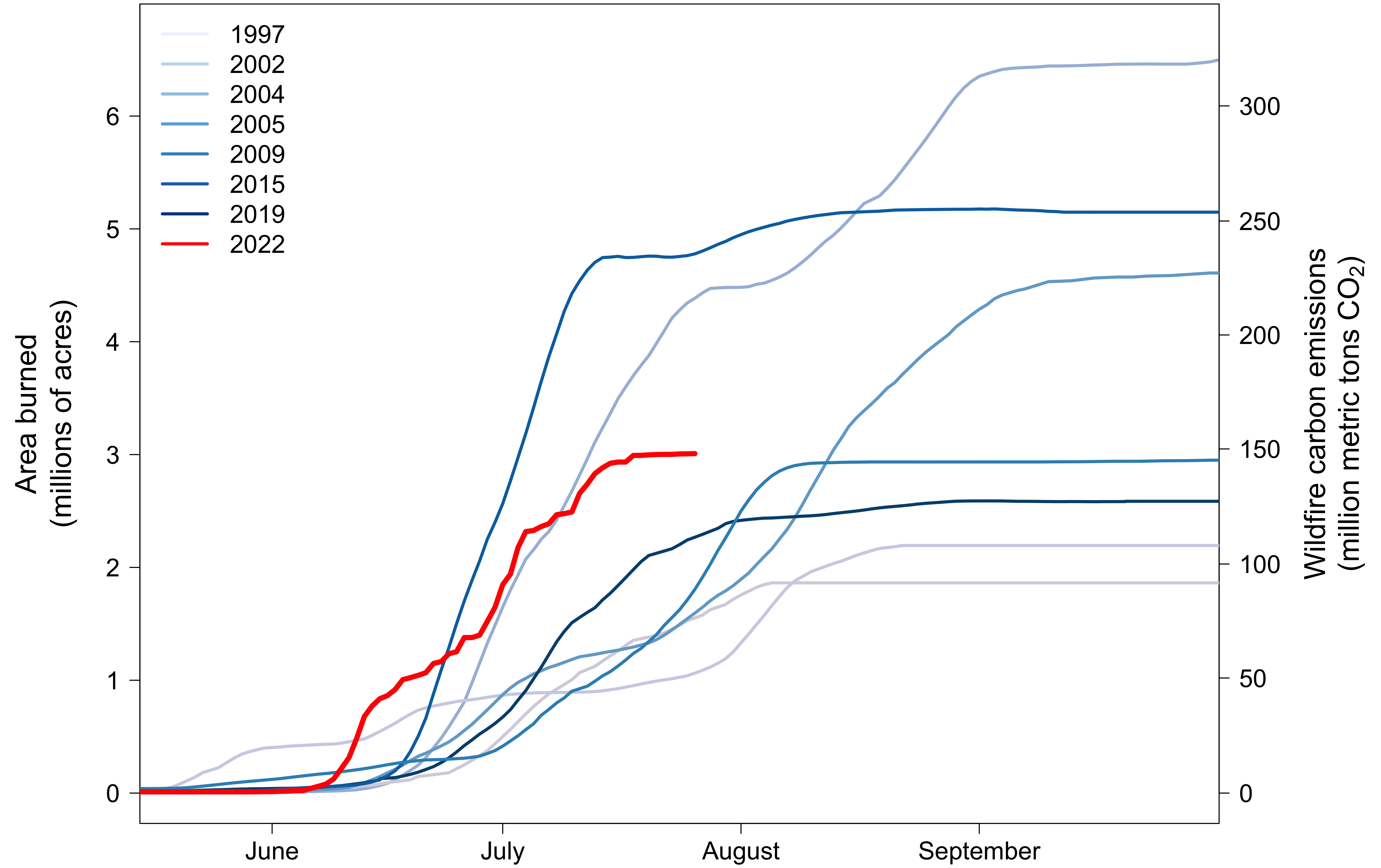

It was supposed to be a quiet season, but only two months into summer and Alaska is already on track for another record-setting wildfire season. With 3 million acres already scorched and over 260 active fires, 2022 is settling in behind 2015 and 2004 so far as one of the state’s worst fire seasons on record. Here’s what to know about Alaska’s summer fires:

graphic by Carly Philips

1. Historic fires are burning in Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta and Bristol Bay

Southwestern Alaska, in particular, has been suffering. The season kicked off with an unseasonably early fire near Kwethluk that started in April. Currently, the East Fork Fire, which is burning near the Yup’ik village of St. Mary’s, AK, is among the biggest tundra fires in Alaska’s history. Just above Bristol Bay, the Lime Complex—consisting of 18 individual fires—has burned through nearly 865,000 acres. One of the longest lasting fires in the Lime Complex, the Upper Talarik fire, is burning close to the site of the controversial open-pit Pebble Mine.

graphic by Greg Fiske

2. Seasonal predictions showed a low-fire season

For Dr. Brendan Rogers, who was in Fairbanks, AK for a research trip in May, the explosive start of the fire season contrasts strongly to conditions he saw in late spring.

“It was a relatively average spring in interior Alaska, with higher-than-normal snowpack. Walking around the forest was challenging because of remaining snow, slush, and flooded trails,” said Dr. Rogers.

Early predictions showed a 2022 season low in fire due to heavy winter snow. But the weather shifted in the last ten days of May and early June. June temperatures in Anchorage were the second highest ever recorded. High heat and low humidity rapidly dried out vegetation and groundcover, creating a tinderbox of available fuel. This sudden flip from wet to dry unfolded similarly to conditions in 2004, which resulted in the state’s worst fire season on record.

3. Climate change is accelerating fire feedback loops

The conditions for this wildfire season were facilitated by climate change, and the emissions that result from them will fuel further warming. The hot temperatures responsible for drying out the Alaskan landscape were brought on by a persistent high pressure system that prevents the formation of clouds—a weather pattern linked to warming-related fluctuations in the jet stream.

“With climate change, we tend to get more of these persistent ridges and troughs in the jet stream,” says Dr. Rogers. “This will cause a high pressure system like this one to just sit over an area. There is no rain; it dries everything out, warms everything up.”

The compounding effects of earlier snowmelt and declining precipitation have also made it easier for ground cover to dry out rapidly under a spell of hot weather. More frequent fires also burn through ground cover protecting permafrost, accelerating thaw that releases more carbon. According to the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy, the frequency of big fire seasons like this one are only increasing—a trend expected to continue apace with further climate change.

Additionally, this summer has been high in lightning strikes, which were linked to the ignition of most of the fires currently burning in Alaska. Higher temperatures result in more energy in the atmosphere, which increases the likelihood of lightning strikes. On just one day in July over 7,180 lightning strikes were reported in Alaska and neighboring portions of Canada.

4. Communities are being affected hundreds of miles away

The destruction from these wildfires has forced rural and city residents alike to evacuate and escape the path of burning. Some residents of St. Mary’s, AK have elected to stay long enough to help combat the fires, clearing brush around structures and cutting trees that could spread fire to town buildings if they alight.

Andreafsky River at St Mary’s with the East Fork Fire in the background. / photo by Alaska Incident Management Team/Jacob Welsh

But the impact of the fires is also being felt in towns not in the direct path of the flames. Smoke particulates at levels high enough to cause dangerously unhealthy air quality were carried as far north as Nome, AK on the Seward Peninsula.

“Even though a lot of these fires are remote, that doesn’t preclude direct human harm,” says Woodwell senior science policy advisor Dr. Peter Frumhoff.

Recent research has shown that combatting boreal forest fires, even remote ones, can be a cost effective way to prevent both these immediate health risks, as well as the dangers of ground subsidence, erosion, and loss of traditional ways of life posed by climate change in the region.

5. The season is not over yet

Mid-July rains have begun to slow the progression of active fires but, according to Dr. Frumhoff, despite the lull, it is important to keep in mind that the season is not over yet.

“The uncertainty of those early predictions also applies to the remainder of the fire season — we don’t know how much more fire we’ll see in Alaska over the next several weeks.”