Woodwell launches new project monitoring, combatting the effects of permafrost thaw

A $41 Million grant through The Audacious Project will fund Permafrost Pathways work

A thawing slope collapses into the water in Siberia.

photo by Chris Linder

It’s a big idea—a pan-Arctic monitoring network for permafrost emissions—but big ideas are exactly what The Audacious Project was created to foster.

This April, Woodwell Climate Research Center was awarded 41.2 million dollars through The Audacious Project to not only build such a network, filling gaps in our understanding of how much carbon is released into the atmosphere from thawing permafrost, but also to put research to work shaping policy and helping people.

The new project, called Permafrost Pathways, combines scientific prowess from Woodwell with policy, community engagement, and Indigenous knowledge from the Arctic Initiative at Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, the Alaska Institute for Justice (AIJ), and the Alaska Native Science Commission.

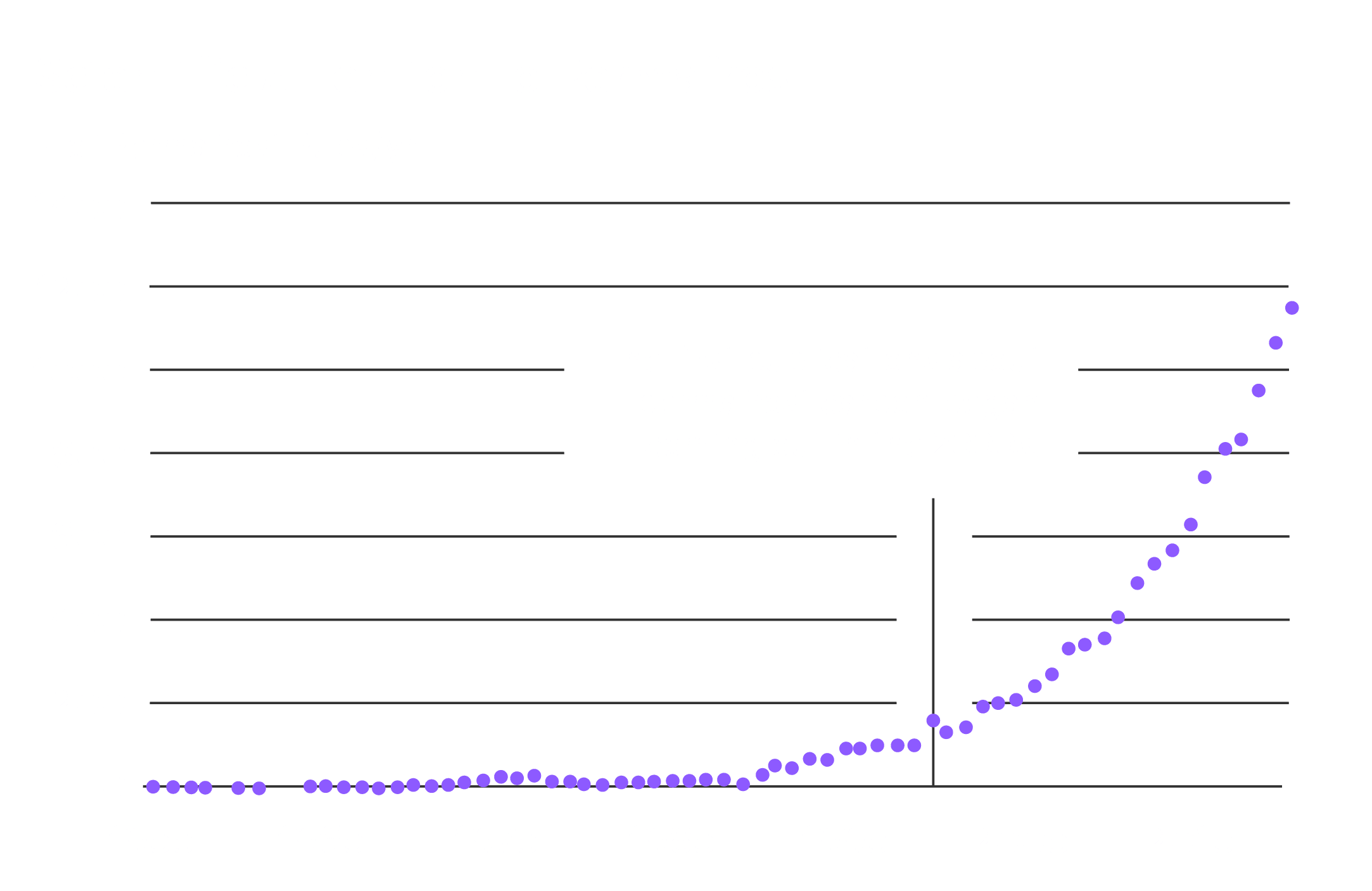

Carbon emissions from permafrost thaw are one of the biggest areas of uncertainty in global climate calculations. Thawing permafrost is expected to release between 30 and 150 billion tons of carbon by 2100, the higher estimates on par with or even exceeding the United States’ cumulative emissions if allowed to continue at current rates. Yet permafrost is not accounted for in carbon budgets and international agreements. Permafrost Pathways will develop more complete data on permafrost carbon and deliver that research into the hands of those poised to decide how we deal with the warming Arctic.

Permafrost cores show ice locked in the soil that thaws rapidly once exposed.

photos by Chris Linder

Big problems require big solutions

Permafrost Pathways is led on the Woodwell side by Arctic Program Director Dr. Sue Natali and Associate Scientist Dr. Brendan Rogers, who have both been researching permafrost carbon for years. Dr. Natali found her way to the Arctic through a desire to work in a place significant to the global carbon story. The rapid changes she has witnessed in the past decade have underscored the Arctic as ground zero for climate change.

“I’ve seen dramatic changes from one year to the next in the places where I work, and Arctic residents have been observing these changes for decades,” Dr. Natali says. “You can measure something one year and then the ground there collapses the next. The physical changes across the landscape are really startling to see.”

Drs. Natali and Rogers have seen eroded hillslopes, research trips abandoned due to wildfire, community meetings with Arctic residents whose homes are sinking—every experience reinforced the fact that there was still much more to learn about how thawing permafrost feeds into climate change and is impacting Arctic communities.

The Audacious grant will allow Drs. Natali and Rogers to pull together the threads of their prior research into a project that starts to tackle the issue on a grander scale.

“When you’re focused on individual problems or hypotheses, you’re not able to really think big about something like monitoring across the Arctic,” says Dr. Rogers. “Opening up a funding source like this lets you think at a scale that matches the problems we face.”

The project is thinking really big, with the goal of installing 10 new eddy covariance towers—structures with instruments that measure carbon flux—in key areas where data is currently lacking. Pathways will also maintain existing key towers that would otherwise be decommissioned, and augment others to measure carbon fluxes year-round.

“There are a lot of existing towers that are either not running through the winter, or they’re not measuring methane, or they’re on hold for instrumentation upgrades or lack of funding,” Dr. Natali says. “We will get even more new data by maintaining old towers than constructing new ones.”

In parallel, Woodwell will work with a team at University of Alaska Fairbanks to develop a novel permafrost model that fully harnesses the data, accounting for important but currently neglected processes, and ultimately delivers more accurate projections of permafrost emissions to inform policy makers and Arctic communities.

GIF by Nichole Chapman and Greg Fiske

‘It’s an awful decision’

While the science team ramps up new data collection, AIJ will be breaking down the issue of adaptation. The Arctic is warming faster than anywhere else on Earth, and it is not waiting for exact measurements to make the consequences known.

The land upon which many Alaska Native communities are located is destabilizing in the face of usteq—a Yupik word for the catastrophic ground collapse that occurs when thawing permafrost, erosion, and flooding combine to pull the ground out from under them. In many places the formerly solid cornerstones of villages—houses, roads, airports, cemeteries—have had to be picked up and moved to more stable ground.

“It is an awful, awful decision that communities are being faced with because the land on which they’re living is becoming uninhabitable,” says Executive Director of AIJ, Dr. Robin Bronen.

An Alaska National Guard building sunk into thawing permafrost.

On top of the trauma of watching their villages sink into the Earth, there is no clear path for Arctic communities deciding they must completely relocate.

“It’s become painfully clear that we in the United States have no institutional or governance structure to facilitate this type of movement of people,” says Dr. Bronen. There is no standardized way for people displaced by the climate crisis seeking resettlement to apply for funding and technical assistance for a community-wide relocation.

“If policy changes aren’t made nationally, then a lot of communities in the United States are going to be experiencing this incredible disconnect between making the decision that they are ready to leave, but having no resources to implement that decision,” says Dr. Bronen.

Permafrost Pathways will be working with Arctic residents to help them adapt to their rapidly shifting landscape. Through AIJ and the Alaska Native Science Commission, the project will connect with communities, collaborate to generate data they can use in their decision making and, if they make the choice to move, work with them to secure the resources needed for relocation.

Factoring permafrost thaw into our global future

Permafrost Pathways isn’t the first to tackle these issues but, Dr. Natali says, it does represent a unique combination of expertise that could push forward both carbon mitigation and climate adaptation policies.

Leader of the Arctic Initiative, professor, and Senior Advisor to Woodwell’s president, Dr. John Holdren understands the value of connections in making lasting change; he has been speaking to top policy makers in the U.S. and abroad for much of his career.

“All of us at the Belfer Center have been linking science and policy for a long time and communication is important to that,” says Dr. Holdren. “In my view, it’s going to remain important to have personal connections at high levels.”

Working through these connections, Permafrost Pathways will put the project’s science into the hands of policymakers to impress upon them the issue’s urgency.

graph by Carl Churchill

“All the news coming out about permafrost carbon has been bad news,” says Dr. Holdren. “I think what we are going to find is that the high estimates are much more likely to be right than the low estimates. We’ve got to get that factored into the policy process.”

For Dr. Natali, the most important outcome of Permafrost Pathways is a future in which the threats presented by permafrost thaw are taken seriously by governments.

“I want to see permafrost thaw emissions accounted for,” says Dr. Natali. “I want to see the national and international community actually wrestle with the effects of permafrost thaw and to take action to respond to the climate hazards.

Dr. Rogers says he hopes the collaborative nature of this already-big project will have even larger, rippling effects—paving the way for new partnerships and policy change.

“There’s the critical work that we will be doing, and then there are the new doors that a project of this scope opens,” says Dr. Rogers. “And we aren’t reaching our end goal without those open doors.”

The Audacious Project is an initiative of the non-profit TED that funds large-scale solutions to the world’s most challenging problems. Every year, the Project selects a cohort of big ideas to nurture with funding and resources.