Study highlights need for better understanding of climate impact on “blue carbon”

[Updated July 20, 2020]

Coastal wetlands and marshes are critical biodiversity hotspots and protect communities from storms. Additionally, they act as important carbon sinks, storing organic carbon in soils that have accumulated over thousands of years. A study published in the September issue of Nature Geoscience by a team including Woodwell Climate Research Center’s Dr. Jonathan Sanderman warns that we don’t know enough about how our rapidly changing climate and coastal development are disrupting them.

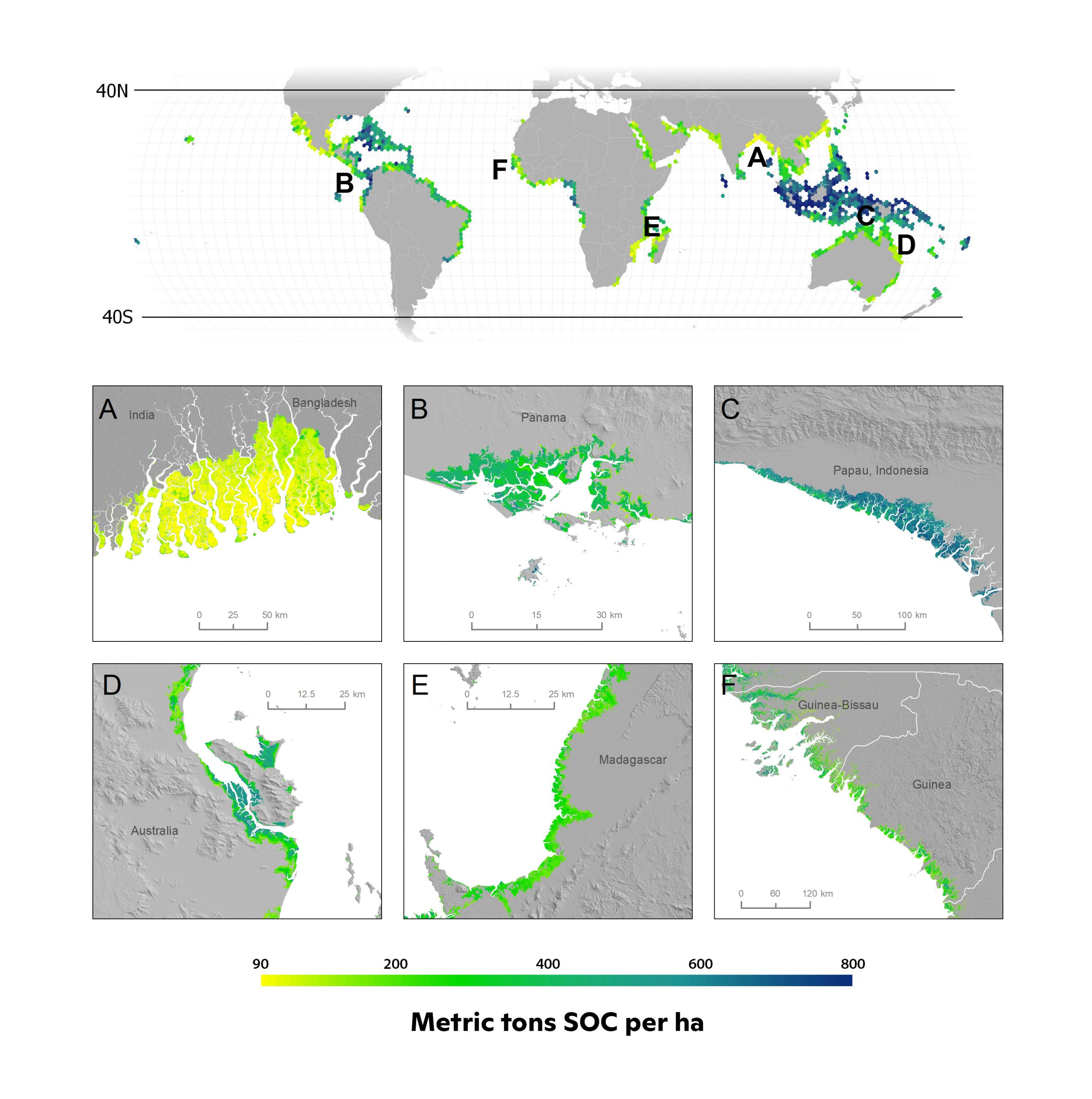

Mangroves, tidal marshes, and seagrass meadows act as important carbon sinks, storing more carbon per unit area than terrestrial forests. Although coastal habitats cover less than 2% of total ocean area, they account for approximately 50% of carbon sequestered in ocean sediments.

Coastal mangroves are commonly found in the tropics and are being lost at a rate of 2% per year.

When degraded or destroyed, these ecosystems release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere that has been stored for centuries. Warming water, rising seas, runoff pollution, and landscape development are impacting microbial community makeup and function, pore water chemistry, and vegetation dynamics.

Taken together, these changes can have major but uncertain impacts on the global reservoir of so-called “blue carbon”—the carbon captured and stored by the world’s ocean and coastal ecosystems.

Excess nutrient runoff, known as eutrophication, has been a focus of The TIDE Project, a study conducted by Woodwell Climate and partners in the Plum Island Estuary of the Great Marsh north of Boston. The research has found loading coastal marshes with nitrogen does a surprisingly large amount of damage, changing vegetative growth patterns and accelerating organic matter decomposition. The result is that marshes struggle to keep up with sea level rise and are more vulnerable to edge collapse.

Above: Photo courtesy of Fishing Cat Conservancy.

“Will salt marshes and mangroves keep up with sea level rise and keep accumulating organic matter, or will degradation alter the cycle? Blue carbon is incredibly important in our understanding of the global carbon cycle, but most of our existing models oversimplify the mechanisms that affect it. This study is a step toward improving predictions of soil organic carbon stores and incorporating coastal vegetated ecosystems into global carbon budgets and management tools,” said Dr. Sanderman.

While this study lays out some of the questions, future research and more dedicated funding will be key to getting answers and supporting more effective ecosystem management. Nonprofit and community-based organizations have already begun the work of studying wetland ecosystems across the world. Fishing Cat Conservancy works around the globe to empower communities to protect wild fishing cats by restoring mangrove habitats. Deakin University’s Blue Carbon Lab has established TeaComposition H20, a global analysis of plant litter decomposition within wetland ecosystems using household tea bags.

Above: Photo courtesy of Fishing Cat Conservancy.

Identifying high-value blue-carbon ecosystems and taking measures to increase their sustainability will also help communities protect infrastructure and plan for our changing climate. Woodwell Climate is working to understand and preserve coastal wetlands and marshes locally and around the globe.

Will salt marshes and mangroves keep up with sea level rise and keep accumulating organic matter, or will degradation alter the cycle?Dr. Jon Sanderman