Mapping the herd: Cartography in the Mongolian Taiga

Senior Geospatial Analyst Greg Fiske explores the power of maps among the Dukha Reindeer herders

A herd of reindeer tended by the Dukha in Mongolia.

photo by Greg Fiske

When I was young, there were always a few horses and ponies on our family farm. I was a pretty good rider. I even showed ponies in the 4-H children’s show at the local county fair.

My previous horse experience, however, proved little help for the day-long horse riding treks I found myself on this summer during a spontaneous trip to Northwestern Mongolia with friend and colleague, Marina Tonkopeeva of the International Center for Reindeer Husbandry (ICR). Tonkopeeva leads a collaborative project with the Dukha, funded by the Global Environment Facility, that is focused on reducing land degradation in Mongolian Peatlands.

map by Greg Fiske

We were there to visit indigenous Dukha reindeer herders in the Taiga regions near Tsagaannuur, not far from the Russian border. The only access to these remote communities, I quickly discovered, was by riding many hours on horseback. Our journey included two separate horse treks, one to the East Taiga camp, home to about a dozen herder families and a second to the more rugged West Taiga region, higher up in the mountains where we met with two families on a much smaller camp in their autumn location. I was forced to relearn horsemanship on the fly across the Mongolian wilderness and was wishing I still had the resilience and physical toughness of my youth.

A trail ride through the Taiga with Dukha reindeer herders.

photo by Greg Fiske

The goal of this trip was exploratory. I hoped to connect with herders, introduce cartography as a powerful tool, and gain first-hand knowledge about the lands I would be mapping. From many other field trips in the past, I’ve learned that there is true inspiration in taking the time to travel to a field site. It allows me, as a cartographer, to build relationships and make connections between my virtual world of geospatial data and reality. Experiencing things like natural colors and landscape dynamics all help with making maps, post-trip.

My goal was also to co-produce maps with the Dukha herders. Co-production of maps essentially means combining Indigenous knowledge with western science and cartography to communicate a story, based on mutual understanding and trust. Through the process of co-production, I can learn about the intended audience of our proposed maps, about how the maps will be used, and what story we will tell with the maps we make together.

With the help of our host and colleague, Khongorzul Mungunshagai, we met with many reindeer herding families and shared detailed satellite images inside their teepees. Over reindeer milk tea and cheese, we discussed migratory paths, seasonal camp locations, and shared stories about regional changes.

Greg Fiske (center), Khongorzul Mungunshagai (right), and Dukha herder Gambat (left) examine maps of important reindeer pasture and migration routes.

photo by Marina Tonkopeeva

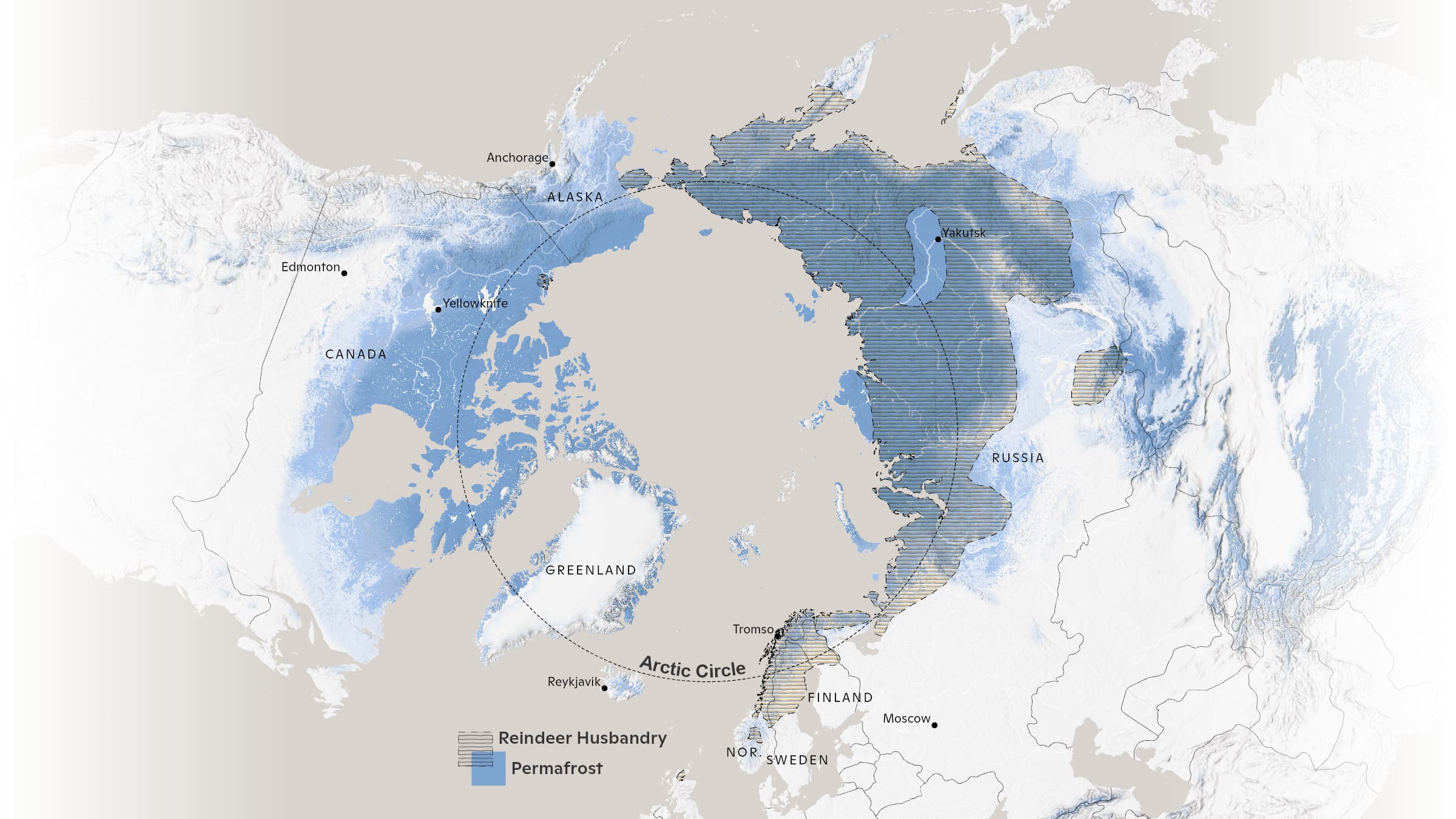

Indigenous communities across the planet have adapted to climate variability for millennia; however, the combined impacts of rapid warming and resource development are having an unprecedented impact on Indigenous peoples and their lands. Reindeer husbandry, which has been practiced for thousands of years, constitutes the modern-day livelihood of tens of thousands of Indigenous people who tend millions of domesticated reindeer on lands that span the Eurasian permafrost region. Traditional reindeer husbandry practices are now being challenged by loss of land due to development, conservation, and climate change.

map by Greg Fiske

The Dukha people of Mongolia, like other indigenous peoples, have lived respectfully and in harmony with the land since time immemorial; however, their lifeways are being challenged by land use decisions that have been implemented without proper consultation and consent. Impacts of these land use changes on traditional grazing lands are being further exacerbated by landscape and landcover changes associated with climate change including increased fire, permafrost thaw, and shrubification. This is of particular concern in Mongolia, where the rate of summertime warming is three times faster than the average for Northern Hemisphere lands, resulting in land degradation from permafrost thaw and changes in vegetation cover due to desertification.

Additionally, the Mongolian government’s new national parks have created unmarked boundaries and land-use restrictions that are essentially invisible lines of attack on the Dukha’s traditional lifestyle. They are being forced to alter ancient migration routes or grazing sites, and they often unknowingly cross park borders because the government hasn’t provided any clear, useful maps.

map by Christina Shintani

Woodwell Climate has recently awarded a Fund for Climate Solutions grant to continue this work. We plan to work closely with Dukha reindeer herders using GIS tools to map land use and land cover changes in Mongolia and their impacts on grazing lands. We will co-produce maps to support climate change research and advocacy for environmentally and culturally-just land management practices. This work would build on past co-production successes working with ICR and Sámi reindeer herders in Norway and with Indigenous communities in Alaska.

It’s clear that maps are a powerful medium for clearly communicating information and important stories. Whether I’m visiting politicians, working with scientists, or gathering in a teepee on the taiga, I’ve found that maps are always a welcome addition to the conversation and they help grease the wheels of communication. Leaving the Taiga and enduring the long trip home, I was physically worn out, but the vision of the Mongolian landscapes and the clarity in the work that lies ahead gave the long trip back purpose. I took home not just memories of making new friends (both two legged and four) and of a stunning ecosystem, but a commitment to help map a path forward with our partners at ICR and the Dukha.