Briefing drives home impacts of climate change on the insurance industry

Insurance policy needs to change with the climate to better protect people

Dominick Dusseau answers questions during congressional briefing.

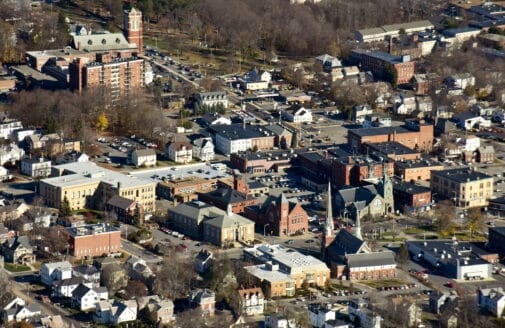

photo courtesy of Environmental and Energy Study Institute

With stronger storms, higher seas, and hotter days, climate change is disrupting the assumptions on which most of our modern systems were established. The insurance industry is feeling the acute impacts of increasingly extreme weather and disaster events, and regulatory policy has failed to keep up—putting communities and companies at risk of huge financial losses.

That’s the message Woodwell Climate Research Associate Dominick Dusseau carried to policymakers during a congressional briefing in Washington DC on May 6. Woodwell Climate has conducted an extensive analysis of climate-caused vulnerabilities within the insurance industry. In a recent policy brief, Dusseau and Policy Analyst Jamie Cummings outlined major risks, as well as proposed regulatory solutions.

One of the chief concerns is the use of “catastrophe models.” Insurance companies calculate potential financial losses from natural disasters based on these models, which estimate the likelihood of something like a category 5 hurricane occurring in a particular year based on historical data. What these catastrophe models generally do not take into account are increases in the frequency and intensity of such events due to climate change. Additionally, population expansion in risk-prone areas continues to increase the potential for damage.

“Climate change is making extreme weather events less predictable and that uncertainty makes it harder for models to get it right,” says Dusseau.

This means the cost of existing insurance policies in high-risk areas like coastal or wildfire-prone communities may not reflect the actual risk to life and property. Alternatively, those insurers who do account for climate change might raise premiums out of the range of affordability or be unable to price high-risk areas appropriately due to regulation and decide an area is altogether uninsurable—a trend being felt acutely in California in recent years.

Catastrophe models are also proprietary, meaning the price of similar insurance policies can vary widely depending on which one a company uses, and lack of transparency leaves the public in the dark on what’s accounting for those differences.

“Depending on which model insurers use, the premiums could be significantly different,” says Dusseau. “This is one of the reasons that greater review and regulation of these models is necessary, so that the risks associated with those premiums are calculated accordingly.”

Solutions, Dusseau and Cummings propose, lie in coherent federal regulation. The brief proposes a national public catastrophe model and rules around fair and appropriate pricing, as well as more accessible public information about insurance. The report also proposes we explore alternative methods of insurance, like parametric policies that cover lost income when a certain metric, like temperature, breaches a threshold, like heat that makes working conditions unsafe.

To get this information into the hands of policymakers, Dusseau participated in a panel briefing for congressional staff hosted by the Environmental and Energy Study Institute (EESI). The briefing identified areas where Congress should play a role in bolstering the long-term resilience and insurability of communities. Dusseau highlighted areas of Woodwell’s report, speaking on the shortcomings of catastrophe models, as well as areas for improvement within the National Flood Insurance Program.

Senator Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island provided opening remarks at the briefing. Whitehouse is the Ranking Member of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee and former chair of the Senate Budget Committee. Through both his current and former leadership positions, he has been a steadfast champion of climate mitigation and adaptation, underscoring the economic ramifications of climate change.

“The insurance industry makes trillion dollar bets anticipating what’s going to happen in the real world, and it also has a fiduciary duty…to get it right,” said Whitehouse.