‘Summer of extremes’ briefing helps meteorologists connect extreme weather events to climate change

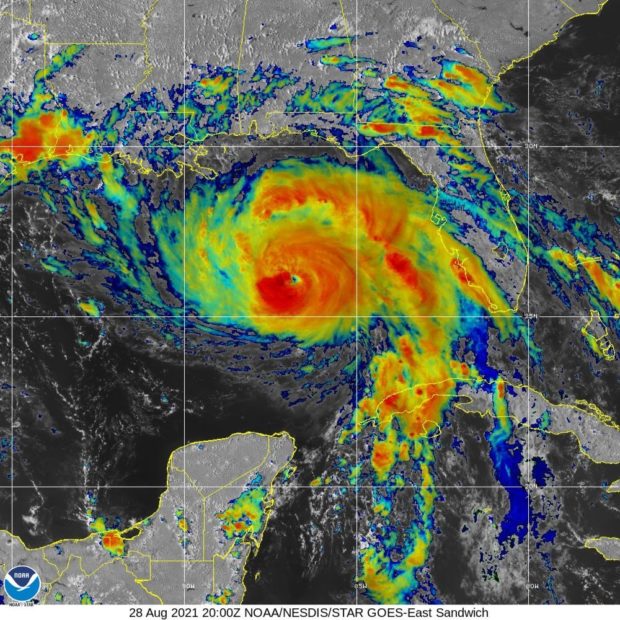

Hurricane Ida, a category 4 storm, made landfall in Louisiana in August 2021.

image by NOAA

The summer of 2021 has been a summer of extremes. Catastrophic wildfires, drought, flooding and deadly heat waves are all signals of a warming climate, but the nature of that connection is often not well understood by the public. To help deepen understanding of the links between extreme weather and climate change, Woodwell hosted a briefing last week for a group that is always thinking about the weather: meteorologists.

The briefing was led by meteorologist Chris Gloninger of KCCI 8 Des Moines, who moderated a Q&A with Woodwell senior scientist Dr. Jennifer Francis and Assistant Scientist Dr. Zach Zobel. Dr. Francis and Dr. Zobel provided attendees with insight into how weather events, like the recent hurricanes Henri and Ida or flash flooding in Tennessee for example, are exacerbated by climate change.

Meteorologists, tasked with preparing local communities for changes in the weather, are uniquely positioned to communicate the role of climate change in weather patterns to a broad public audience. According to Dr. Francis, meteorologists are “often the only scientists that people come into contact with.” Which means they have a valuable opportunity to shape people’s perception of weather events as a consequence of climate change.

For Dr. Zobel, a meteorologist by training himself, one of the best ways to make those connections is by highlighting the specific elements of extreme events that the science shows are clearly linked to warming.

“Rather than focus on the storm itself, focusing on the features within the storm that climate models and observations show are clearly going to increase,” Dr. Zobel said. He cited the all time record for the amount of rainfall in one hour in New York that was broken during Henri. Heavy bursts of precipitation are likely to become more common with climate change, as a warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapor.

Meteorologists joined the briefing from across the United States, and were interested in the best ways to communicate climate science across diverse audiences, some of which might not be familiar with or accepting of climate science. Dr. Francis used the example of farmers in the Midwest who have reported more persistent weather conditions—longer droughts or storms—affecting their crops.

“If we can take that and link it back to how we think climate change is starting to cause more persistent weather patterns, that is something we can talk to them about that is really affecting how they do their business, how they live their lives, and is certainly something they are seeing every day,” Dr. Francis said.

Dr. Zobel also emphasized the need to communicate climate change in terms of personalized, individual impacts.

“Until we are able to do that, climate change may seem like a distant, far away problem,” Dr. Zobel said. “Once people see it’s affecting them locally they tend to re-evaluate.”