| Present | 2040-2060 | 2070-2090 | |

| Return Period (yr) | 1-in-100 | 1-in-50 | 1-in-32 |

| 100-Year | 7.6 in (193 mm) | 8.7 in (221 mm) | 9.9 in (251 mm) |

Climate Risk Assessment: New Bedford, Massachusetts

Introduction

The impacts of climate change on the frequency and severity of physical hazards are putting many communities at risk. As the threat of climate change grows, so too does the need for accessible information, tools, and expertise to support climate-resilient decision making across multiple scales, from communities to countries. Woodwell Climate Research Center believes there is a need to localize and customize climate risk assessments. This information is critical for local government leaders as they make planning decisions, but it is not available to all communities. Woodwell believes that this science should be freely and widely available. To address this gap, Woodwell works with communities across the world, including New Bedford, MA, to provide community climate risk assessments, free of charge. We focused our modeling efforts on a select number of neighborhoods and streets, rather than the entire city of New Bedford, in order to directly respond to community priorities and address a specific, localized flood modeling challenge.

Results summary

As a result of climate change, flood risk is projected to increase for New Bedford. The probability of the historical 100-year rainfall event, a useful indicator of flood risk, is expected to double by mid-century and be more than three times more likely by the end of the century. Heavier rainfall will translate into slightly greater flood depths and extent for New Bedford. Making changes to the land elevation and culverts will help alleviate some of the flooding near Terry Lane and Chaffee Street. Here we present our findings on extreme precipitation and flooding to help New Bedford in its plans to create a more resilient future for all residents.

Extreme rainfall

The Fifth National Climate Assessment shows that the U.S. Northeast region has already seen a 60% increase, the largest in the U.S., in annual precipitation occurring from the heaviest 1% of events.1 Future warming is expected to continue this trend of intensification, meaning more frequent and severe rainfall events. Here, we use localized future precipitation data from downscaled global climate models to calculate the change in probability of extreme rainfall events. A detailed explanation of the precipitation data processing can be found in the methodology section of this document. In Table 1, we show the changes in the return period of the present-day (2000–2020) 100-year rainfall event for mid-century (2040–2060) and late-century (2070–2090). By mid-century, the present-day 100-year event will occur with a return period of 1-in-50. By late-century, the present-day 100-year event will become a 1-in-32 year event.

According to the National Atlas 14 published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the 100-year rainfall amount, based on present-day rainfall records, for New Bedford is 7.6 inches (193 mm).2 For reference, the present-day annual average rainfall for the New Bedford Municipal Airport is 45.9 inches (1165 mm).3 By mid-century, the 100-year amount will increase to 8.7 inches (221 mm) and by late-century this will further rise to 9.9 inches (251 mm; Table 1).

Flooding

For a detailed explanation of the flood model input data and flood modeling procedures, please refer to the methodology section of this document.

Flood extent comparison

Before estimating future flood risk, we like to compare the present-day flood risk results against the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) flood maps. However, FEMA maps have the section of New Bedford that we are interested in categorized as an ‘Area of Minimal Flood Hazard’. The likely reason for this is that FEMA focuses on fluvial flooding, which is flooding associated with water level changes in rivers, lakes, and streams, but does not take into account pluvial flooding. Intense rainfall events fall into the pluvial category and are not included in FEMA maps. It appears that for this region of New Bedford, FEMA maps were updated in 2021. However, this does not include flooding associated with Ousamequin Creek (not the official name) that flows directly through this part of New Bedford, which also likely contributes to FEMA’s lack of flood risk in this area.

Present and future flood risk

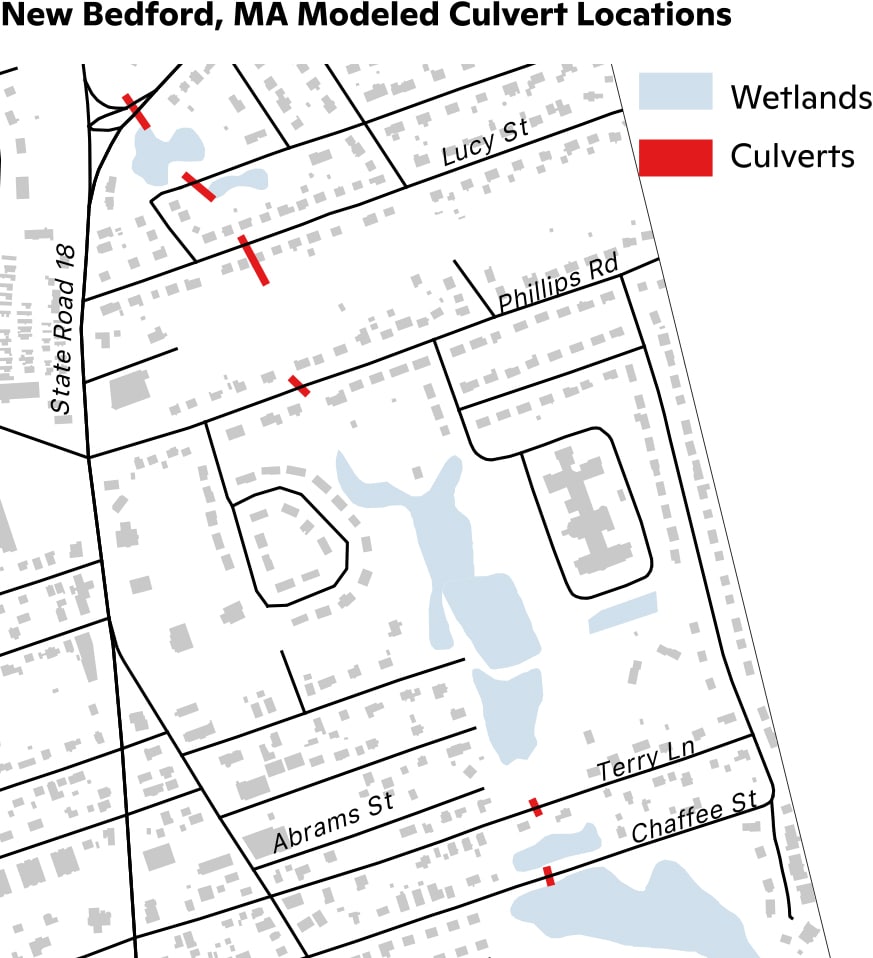

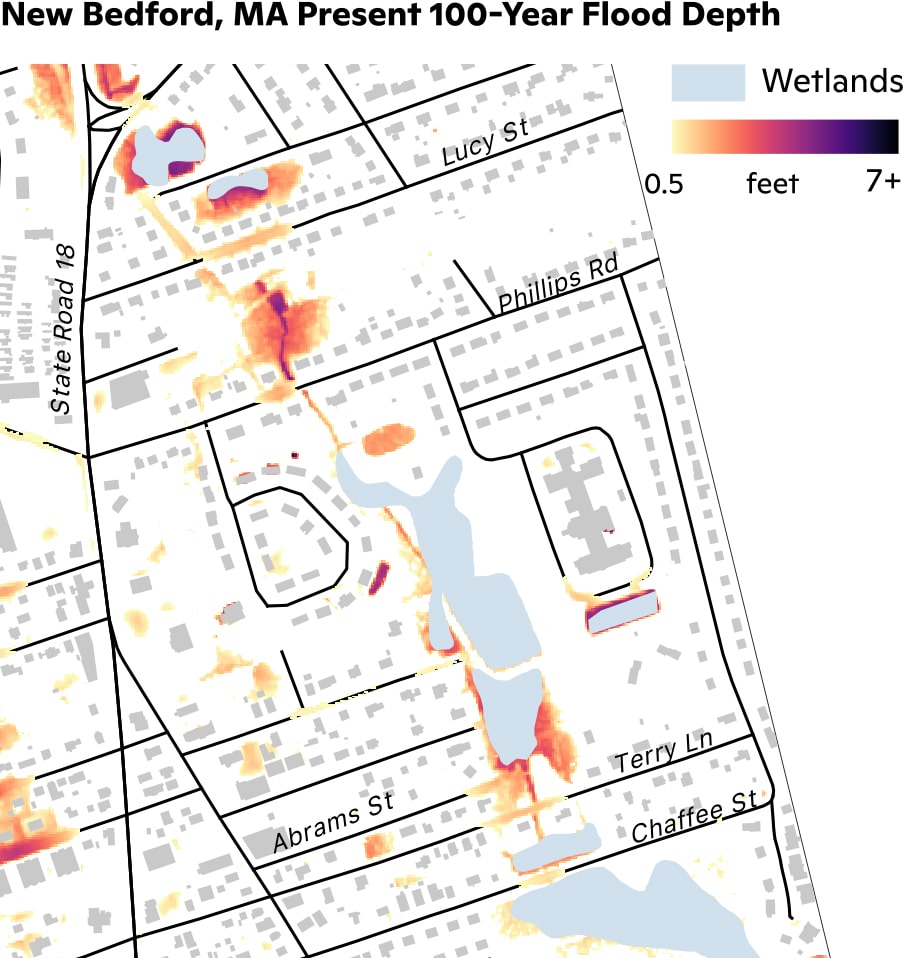

The primary flood risk in this area of New Bedford, MA, is from extreme rainfall. To accurately model this extreme rainfall, we included several culverts from Acushnet Avenue south to Chaffee Street, shown in Figure 1, the conveyance for them can be found in Table 2. In Figure 2, we show the depth of the present 100-year flood from rainfall for New Bedford. The highest depth values of around 1.6 ft (0.5 m) occur in several locations. Some examples are Lucy Street, Phillips Road, and Terry Lane. Flooding on Chaffee Street is also substantial, with a maximum depth of approximately 0.85 ft (0.26 m). We mask wetland areas to focus the analysis on locations where human life and property are at risk.

| Culvert location | Conveyance (%) |

| Acushnet Avenue | 100 |

| Winston Street | 100 |

| Lucy Street | 100 |

| Phillips Road | 30 |

| Terry Lane | 85 |

| Chaffee Street | 85 |

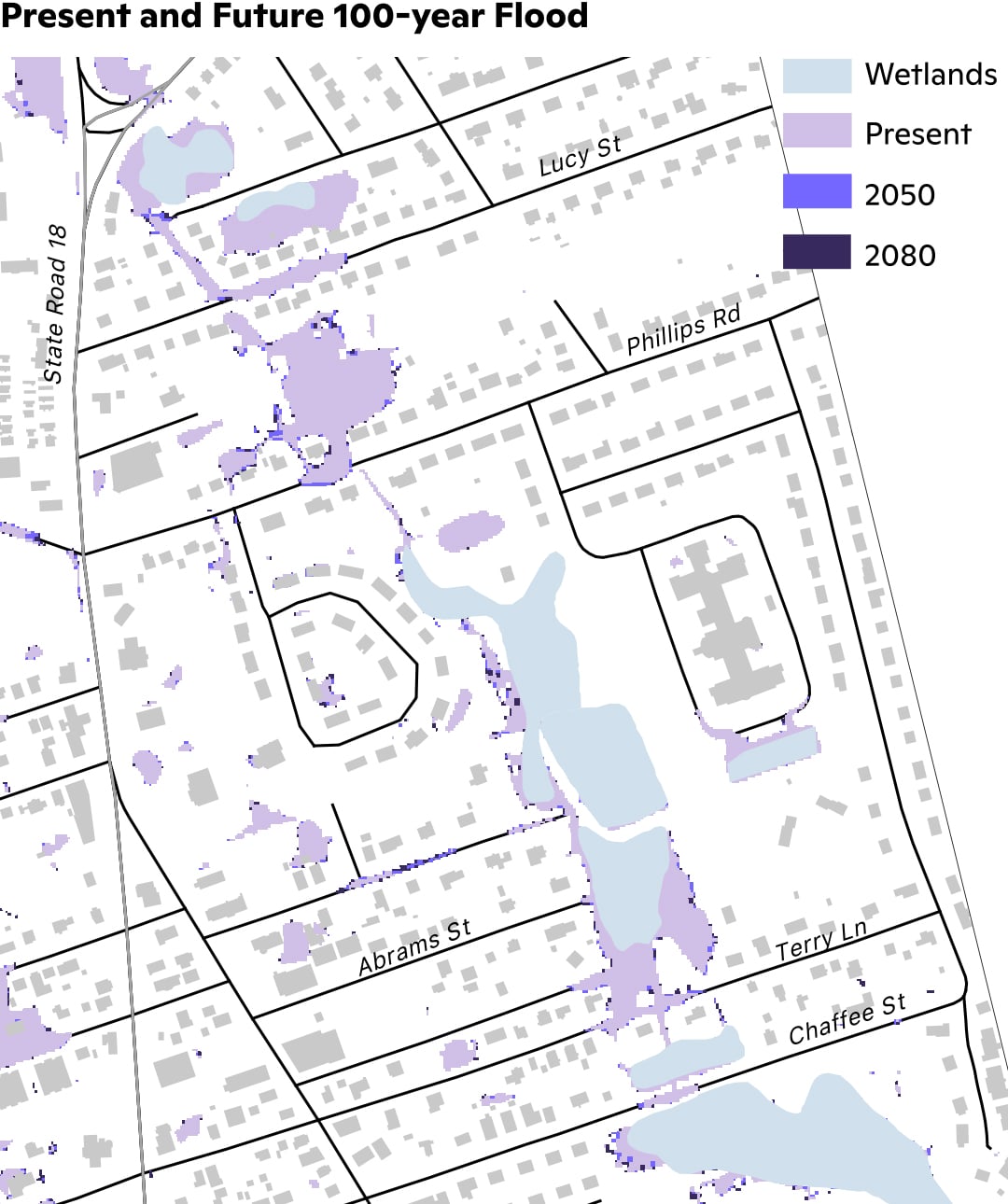

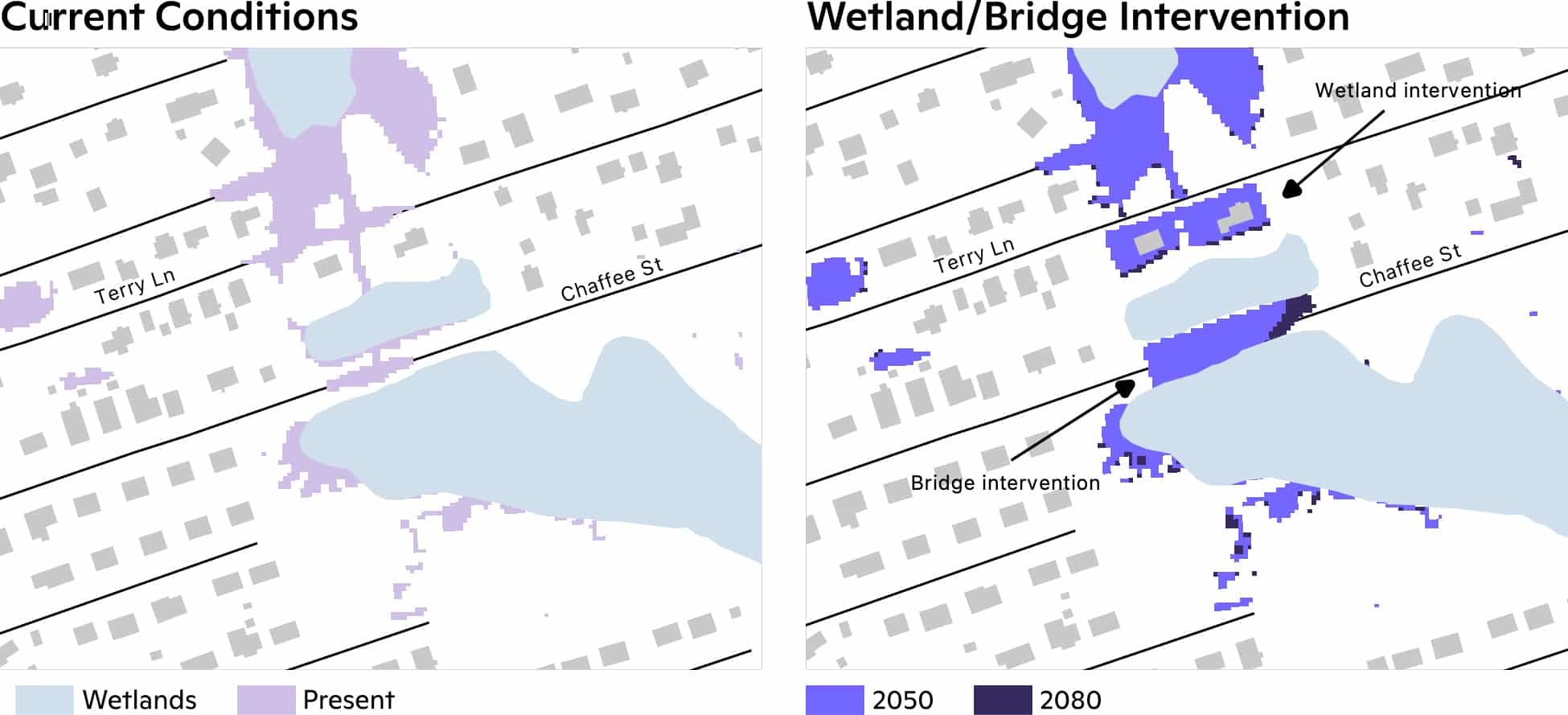

Future flood risk is driven by increased rainfall. Overall, the changes in extent are minor and are shown in Figure 3. This change in pluvial flood risk is due to projected increases in rainfall between 1.1 inches to 2.3 inches (28–58 mm) from the present-day period, as shown in Table 1. Since the extent doesn’t increase substantially, the wetland areas in this section of New Bedford are able to store the increased amount of precipitation. While the extent doesn’t increase much, the areas that flooded previously, Terry Lane and Chaffee Street in particular, will continue to be inundated.

Culvert modifications

To explore potential changes that could be made to culverts and wetlands, we also did two additional future model runs for 2050 and 2080 to compare to the previously discussed results. We set conveyance through the culverts at 100% meaning there is no debris or anything blocking the flow of water through any of the culverts shown in Figure 1. We also used the previous work done for New Bedford, Stormwater Collection System Needs and Issues, created by CDM Smith, that proposed a box culvert at Terry Lane to reduce flooding. Based on this, the culvert at Terry Lane was made into a 4 ft by 6 ft box culvert to allow for more flow. Additionally, for these model runs, we convert the area between Terry Lane and Chaffee Street into a wetland by lowering the elevation just south of Terry Lane so there is additional water storage space. Lastly, we are treating Chaffee Street as having a bridge that spans across the flooded section. In Figure 2, the depth was approximately 0.85 ft (0.26 m) so we assume a bridge spanning this area would at minimum need to be approximately 1–2 ft above its present elevation to allow water to freely flow underneath southward. These elevation changes are shown in Figure 4. Figure 5 shows the result of these modifications. The flooding on Terry Lane is greatly reduced in this scenario by allowing all the water that was on the street to flow southward. Visually, Chaffee Street appears more flooded, but since the road would be higher, this shows all the water flowing under the created bridge. Figure 5 shows the changes that were made to the elevation to include the new wetland area just south of Terry Lane and to make changes to Chaffee Street.

Conclusion

New Bedford is currently at risk from flooding, primarily from extreme rainfall events, and this exposure will only increase under climate change. The results presented in this study were compared to FEMA’s maps, which denote the lack of a flood zone in this section of New Bedford, revealing significant discrepancies due to the exclusion of pluvial flooding in FEMA’s analysis. Our findings show an expected increase in the frequency and intensity of heavy rainfall, with the probability of the present-day 100-year rainfall event to be twice as likely by the mid-21st century and just over three times as likely by the end of the century. New Bedford’s culverts aren’t able to handle the water capacity required presently, so enlarging the culvert at Terry Lane and creating a wetland area just south of the road is recommended. To further mitigate flooding, Chaffee Street could be raised by installing a bridge to allow the water to flow southward. This report provides insight into the climate vulnerability of the City of New Bedford, where an increasing area will be exposed to increased flood waters and more frequent flood events by the end of the century, and it provides ways to proactively mitigate the harmful effects of extreme flooding that the city faces.

1 Marvel et al. (2023). Ch. 2. Climate trends. In: Fifth National Climate Assessment. Crimmins, A.R., C.W. Avery, D.R. Easterling, K.E. Kunkel, B.C. Stewart, and T.K. Maycock, Eds. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH2

2 NOAA calculates extreme rainfall frequencies with all available station data.