Significance of community-held territories in 24 countries to global climate

Rights + resources initiative

Decades of inaction and watered-down commitments have pushed the planet to the brink of potentially irreversible changes, with untold consequences for life as we know it. Failure to meet the goals of previous international conventions and agreements could presage a similar fate for the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals if leaders and decision makers do not heed the message of Indigenous Peoples, Afro-Descendant Peoples and local communities—and particularly the women within these groups: that no plan to save the planet can succeed if it excludes the very people who, for generations, have stewarded the world’s lands and waters, helping to maintain the biodiversity and ecosystem services upon which all life depends.

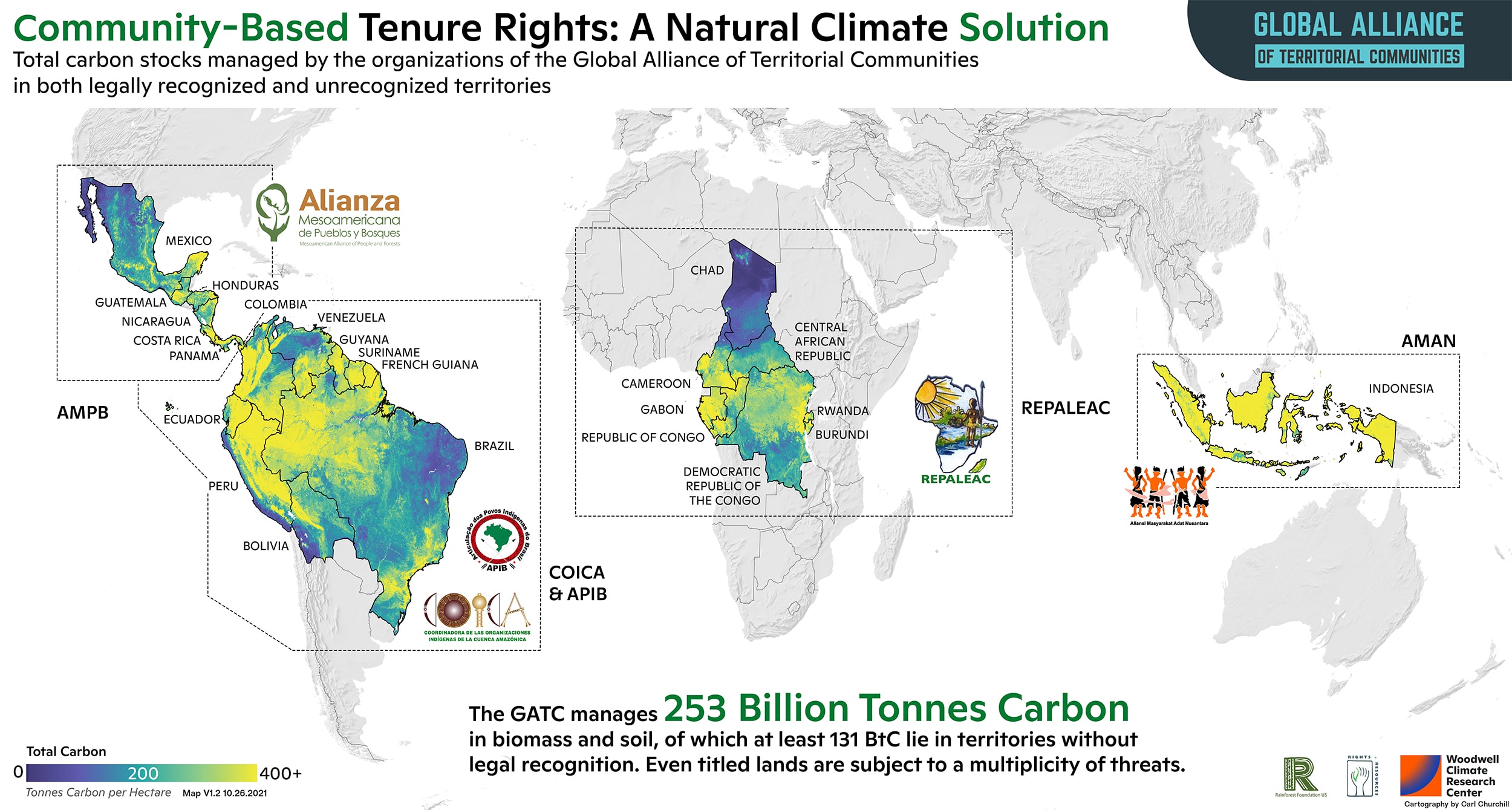

Over the course of a series of high-level summits to develop the post-2020 agenda, the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities (GATC) has emerged as a leading voice, representing the concerns and demands of traditional communities across 24 countries containing 60% of the world’s tropical forest area.1 In response to the GATC’s leadership, the Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI), Woodwell Climate Research Center, and Rainforest Foundation US (RFUS) have jointly consolidated and produced new research based on the latest available geospatial data, official figures, and independently validated area estimates in order to better understand the scale and significance of GATC members’ contributions to the climate and biodiversity agenda.

This research provides a timely reminder of the global significance of community-held lands and territories; their importance for the protection, restoration, and sustainable use of tropical forestlands across the world; and the critical gaps in the international development architecture that have so far undermined progress towards the legal recognition of such lands and territories.

Our findings indicate that Indigenous Peoples, Afro-Descendant Peoples, and local communities customarily hold and use at least 958 million hectares (mha) of land in the 24 reviewed countries but have legally recognized rights to less than half of this area (447 mha). Their lands are estimated to store at least 253.5 Gigatons of Carbon (GtC), playing a vital role in the maintenance of globally significant greenhouse gas sinks and reservoirs. However, the majority of this carbon (52 percent, or 130.6 GtC) is stored in community-held lands and territories that have yet to be legally recognized.

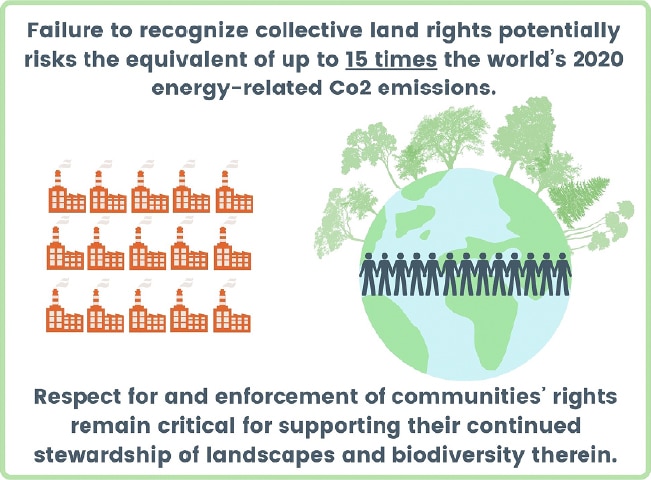

This absence of tenure security renders communities and their lands and forests vulnerable to encroachment and external pressures, hampering their ability to sustainably govern these areas, pursue their self-determined priorities, and meet their livelihood needs.

Urgent need for transformative action

There is now growing consensus that secure collective land rights are fundamental to the realization of just, effective, and sustainable climate and biodiversity actions and the transformative changes that are urgently needed.2 Despite such recognition, climate financing institutions have yet to dedicate the resources required to secure communities’ land tenure rights. In fact, less than 1% of official development assistance for climate change mitigation and adaptation has been earmarked for community forestry over the last decade, and only a tiny fraction of this amount was dedicated to projects advancing collective land and forest tenure rights.3

Moreover, analysis of nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to the Paris Agreement finds that the governments of only eight of the 24 GATC member countries have committed to strengthening community land rights as a part of their climate change strategies.4 Whether these non-binding commitments translate into action remains to be seen, but in the absence of dedicated international financing support and effective recognition of community-held lands and territories, the risk of furthering forest and biodiversity loss, land-related conflicts, and the weakening of the 2030 sustainable development agenda remains high. Yet, an RRI review of opportunities to accelerate tenure reforms in countries with GATC presence shows that such changes are both possible and actionable. Of the 24 jurisdictions analyzed, 22 have at least one legal framework for recognizing communities’ tenure rights, and, of those, at least 10 have legislation for recognizing their full ownership rights.5 For example, by implementing existing legislation in just two countries–Indonesia and Democratic Republic of the Congo–over 200 mha of Indigenous and local community lands could be recognized, helping to protect an area larger than the combined area of the European Union’s five largest member states: France, Spain, Sweden, Germany, and Poland.

Of the 20 countries where RRI completed assessments of the political-economic context and institutional capacities, at least 14 countries have satisfactory or partially satisfactory enabling conditions to implement tenure reform overall, though government willingness to support such processes was found to be inadequate or only partially inadequate in 15 of the 20 countries.6 But as history reveals, policy positions and perspectives are dynamic and everchanging.

Within the contexts of the global climate and biodiversity talks, the growing demand for rights-based actions presents unparalleled opportunities to both galvanize political support for this critical agenda and mobilize the financial and technical resources needed to help countries deliver on this crucial step toward a more just and sustainable future. Achieving such ends may require the international community to redefine what counts as a climate contribution when all ecosystem services are required for a stable planet, and how to make the legal recognition and protection of community-held lands and territories a central tenet of all national and international actions, commitments and investments.

Evidence shows that the land stewardship and sustainable development contributions of Indigenous Peoples, Afro-Descendant Peoples, and local communities are so globally significant that the world can simply not afford to exclude them from critical decision-making processes. Securing and protecting their rights and livelihoods are necessary steps for averting systemic risks that could further accelerate the unfolding global environmental crises. More must be done to strengthen and expand communities’ tenure rights, leverage all performance and market-based financing mechanisms, frameworks, and approaches to achieve such ends, and ensure rightsholders are involved in all future land use and land conservation decisions.

The stability of the climate and the future of humanity now depend on the creation of policy mechanisms that value not only the sequestration capacity of community-held lands and forests, but also the standing stocks of carbon, together with the broad range of globally significant ecosystem services that communities across the tropics manage and maintain.

Call to action

As negotiators and decision makers grapple with how to secure a safer, healthier planet for current and future generations, the rights of Indigenous Peoples, Afro-Descendant Peoples, and local communities can no longer be an afterthought. They must be recognized as central to the realization of global climate and biodiversity goals. In order to empower them to play their vital role in protecting lands and forests, the following five principles should be understood as nonnegotiable for a just transition:

- Recognition and enforcement of the land, territorial, and resource rights of Indigenous Peoples, Afro-descendant Peoples, and local communities – and the women within these groups.

- Respect for the right to free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) where projects may impact community territories.

- Increase dedicated climate, conservation, and development funding and direct access for communities and the initiatives they lead to secure, protect and steward their lands, and ensure their full and effective participation in all nature-based climate and conservation actions and decisions, from design through implementation.

- An immediate end to criminalization, intimidation, and killing of Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and community land and environmental rights defenders.

- Incorporation of traditional knowledge into climate change policies and practices.

For more information on these findings, please contact Chloe Ginsburg at cginsburg@rightsandresources.org.

1 The 24 jurisdictions where GATC has members are: Bolivia, Brazil, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Colombia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Costa Rica, Ecuador, French Guiana (France), Gabon, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Indonesia, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Suriname, and Venezuela. Within this brief, area-based information concerning French Guiana is specific to the administrative department, whereas legal analysis considers the national laws and international commitments made by France as appropriate. Tropical forest area is calculated using data from FAO. 2020. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020: Main report. Rome. Available at: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/ca9825en/. See also GATC website: https://globalalliance.me/.

2 See Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2019. Special Report on Climate Change and Land. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/; FAO and FILAC. 2021. Forest Governance by Indigenous and Tribal People. An Opportunity for Climate Action in Latin America and the Caribbean. Santiago. Blackman, A. 2015. Strict versus Mixed-use Protected Areas: Guatemala’s Maya Biosphere Reserve. Ecological Economics 112: 14–24; Nepstad, D. et al. 2006. Inhibition of Amazon Deforestation and Fire by Parks and Indigenous Lands. Conservation Biology 20(1): 65–73; Nolte, C. et al. 2013. Governance Regime and Location Influence Avoided Deforestation: Success of Protected Areas in the Brazilian Amazon. PNAS 110(13): 4956–4961; Stevens, C. et al. 2014. Securing Rights, Combating Climate Change: How strengthening community forest rights mitigates climate change. WRI and RRI, Washington, DC; Wren-Lewis, L., Becerra-Valbuena, L., & Houngbedji, K. 2020. Formalizing land rights can reduce forest loss: Experimental evidence from Benin. Science Advances, 6(26).

3 Rainforest Foundation Norway (RFN). 2021. FALLING SHORT Donor funding for Indigenous Peoples and local communities to secure tenure rights and manage forests in tropical countries (2011–2020). Available at: https://www.regnskog.no/en/news/falling-short.

4 These countries are Bolivia, Cameroon, Chad, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Indonesia, and Nicaragua.

5 The two countries lacking any legal framework for recognizing community-based tenure rights are: Burundi and Rwanda.

6 For more on the updated methodology employed for this assessment see: Rights and Resources Initiative. 2021. Supplement: Opportunity Framework 2021. Rights and Resources Initiative, Washington, DC. Available at: https://rightsandresources.org/publication/global-significance-of-community-held-territories-in-24-countries-to-climate-goals. See also: Rights and Resources Initiative. 2020. The Opportunity Framework 2020. Rights and Resources Initiative, Washington, DC. Available at: https://rightsandresources.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Opp-Framework-Final.pdf.

About the Rights and Resources initiative

The Rights and Resources Initiative is a global Coalition of 21 Partners and more than 150 rightsholders organizations and their allies dedicated to advancing the forestland and resource rights of Indigenous Peoples, Afro-descendant Peoples, local communities, and the women within these communities. Members capitalize on each other’s strengths, expertise, and geographic reach to achieve solutions more effectively and efficiently. RRI leverages the power of its global Coalition to amplify the voices of local peoples and proactively engage governments, multilateral institutions, and private sector actors to adopt institutional and market reforms that support the realization of their rights and self-determined development. By advancing a strategic understanding of the global threats and opportunities resulting from insecure land and resource rights, RRI develops and promotes rights-based approaches to business and development and catalyzes effective solutions to scale rural tenure reform and enhance sustainable resource governance. RRI is coordinated by the Rights and Resources Group, a non-profit organization based in Washington, DC. For more information, please visit www.rightsandresources.org.

More than 100 countries agree: It’s time to end deforestation

Together they represent more than 85 percent of the world’s forests

Leaders from more than 100 countries pledged to halt deforestation by 2030, as part of an agreement inked Tuesday at COP26, the United Nations climate summit taking place in Glasgow, Scotland.

The U.S., Brazil, and Russia were among the nations that signed the agreement, which is backed by more than $19 billion in public and private funding. Representing more than 85 percent of the world’s forests, the signatories committed to protecting and restoring forests while promoting sustainable land-use and agricultural practices.

Combating deforestation is seen as a crucial step in limiting the impacts of climate change, as the world’s forests absorb roughly one-third of carbon emissions annually. Agriculture, forestry and other land uses account for nearly a quarter of global greenhouse-gas emissions, according to the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Read the full article on Grist.

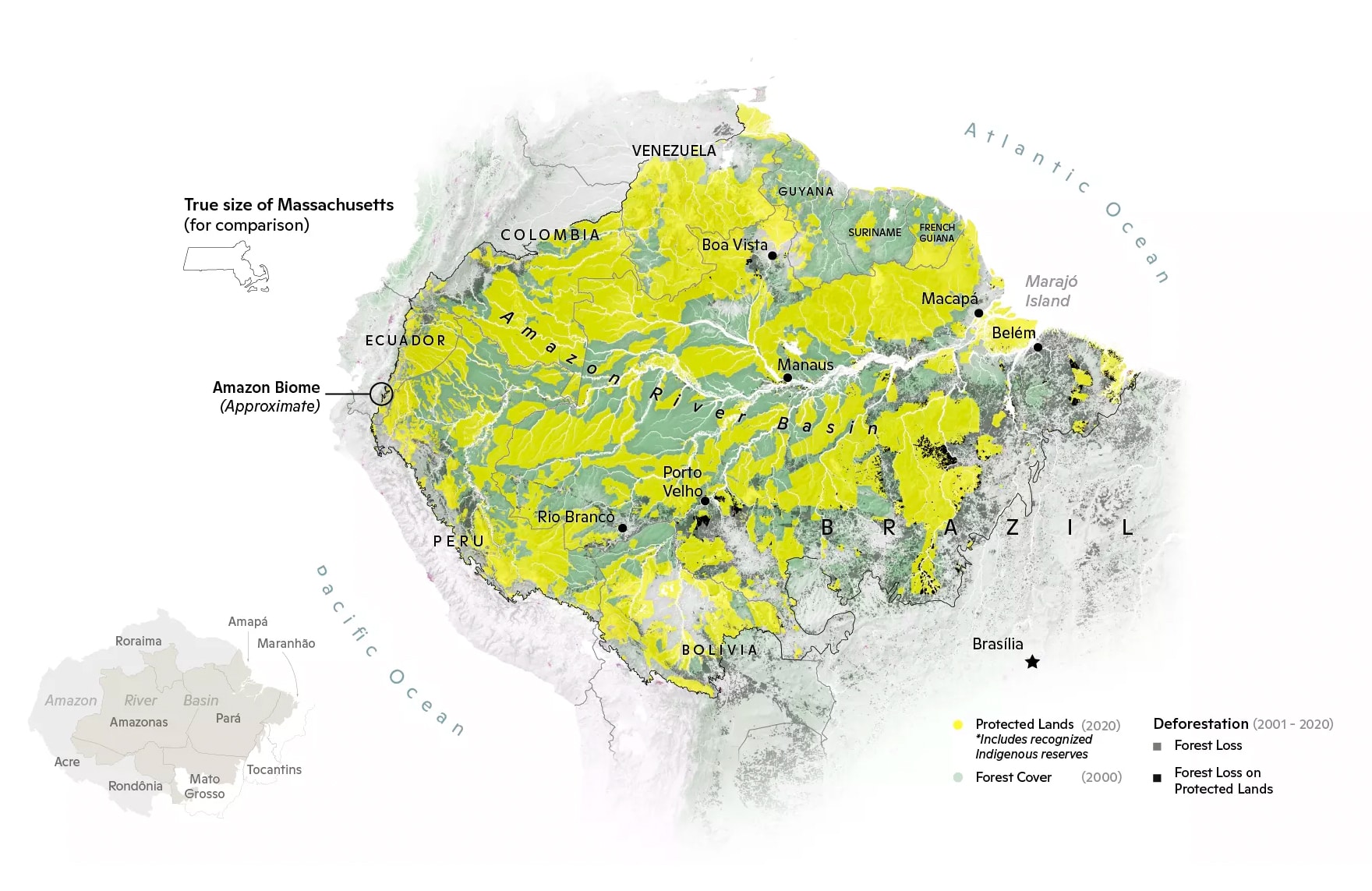

Protected land status determines a forest’s fate

With a global initiative on deforestation announced in Glasgow Monday, there’s a spotlight shining on places like the Amazon.

Researchers say that land status, such as whether a swath of rainforest is within a protected reserve or recognized indigenous lands, can be the determining factor in deforestation.

Why it matters: Due to land clearing for agriculture or other uses, parts of the Amazon have already passed a tipping point from a net absorber of carbon emissions to a net source, and the pace of deforestation has increased in recent years, threatening the Paris Agreement’s temperature targets.

Read the full article on Axios Generate.

Protect old growth

Of all the tools we have to fight climate change, there’s one we’re destroying instead of deploying—trees.

Restoring and expanding forests is vitally important, but no substitute for preserving the forests we have.

Protect old growth forests now.

Preventing catastrophic climate change will require not only the elimination of fossil fuel emissions, but also pulling significant amounts of carbon back out of the atmosphere. Natural ecosystems, from forests to marshes, currently absorb and hold a quarter of human carbon dioxide emissions, and there is potential for nature to do even more.

But nature, alone, cannot meet the full scope of the challenge. On the other hand, new technologies may not be viable soon enough to make a difference. We bring together diverse expertise to explore the combined potential of natural and technological carbon capture and storage for restoring a stable climate.

Watch the video recording.

Vapor storms are threatening people and property

More moisture in a warmer atmosphere is fueling intense hurricanes and flooding rains

The summer of 2021 was a glaring example of what disruptive weather will look like in a warming world. In mid-July, storms in western Germany and Belgium dropped up to eight inches of rain in two days. Floodwaters ripped buildings apart and propelled them through village streets. A week later a year’s worth of rain—more than two feet—fell in China’s Henan province in just three days. Hundreds of thousands of people fled rivers that had burst their banks. In the capital city of Zhengzhou, commuters posted videos showing passengers trapped inside flooding subway cars, straining their heads toward the ceiling to reach the last pocket of air above the quickly rising water. In mid-August a sharp kink in the jet stream brought torrential storms to Tennessee that dropped an incredible 17 inches of rain in just 24 hours; catastrophic flooding killed at least 20 people. None of these storm systems were hurricanes or tropical depressions.

Read the full article by Dr. Jen Francis on Scientific American.

Greenhouse gas emissions from burning US-sourced woody biomass in the EU and UK

Summary of research findings

Introduction

As more and more countries adopt climate targets to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions, the relevance of forests as stores of sequestered carbon has increased. However, the growing use of forest biomass to generate electricity and heat has raised concerns over the immediate emissions resulting from burning wood.

Many national and intergovernmental policy frameworks, including those of the EU and UK, currently treat biomass energy as zero-carbon at the point of combustion. Accordingly, they grant it access to financial and regulatory support available for other renewable energy sources. These incentives have driven a rapid increase in the consumption of biomass for energy, even though its combustion may increase atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO₂) for years or even decades to come.

This report examines the issue in relation to one particular source of woody biomass: wood pellets sourced from the US that are burnt for electricity and combined heat and power (CHP) in the EU and UK. Although wood pellets represent only a proportion of the total woody biomass consumed for energy in the EU–and of forest harvests in the US–the market has grown rapidly in recent years. US-sourced pellets account for the majority of wood pellet imports to the UK and are an important source for the EU.

In 2019, according to our analysis, US-sourced pellets burnt for energy in the UK were responsible for 13 million–16 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions, when taking into account emissions from their combustion and their supply chain, forgone removals of CO₂ from the atmosphere due to the harvest of live trees and emissions from the decay of roots and unused logging residues left in the forest after harvest. Almost none of these emissions are included in the UK’s national greenhouse gas inventory; if they were, this would have added between 22 and 27 percent to the emissions from total UK electricity generation, or 2.8–3.6 percent of total UK greenhouse gas emissions in 2019. This volume is equivalent to the annual greenhouse gas emissions from 6 million to 7 million passenger vehicles.

Emissions from US-sourced biomass burnt in the UK are projected to rise to 17 million–20 million tonnes of CO₂ a year by 2025. This represents 4.4–5.1 percent of the average annual greenhouse gas emissions target in the UK’s fourth carbon budget (which covers the period 2023–27), making it more difficult to hit a target which the government is currently not on track to achieve in any case.

While emissions are likely to fall by 2030, with the end of government support for power stations converted from coal to biomass, they could rise again thereafter if bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) plants are developed at scale.

Conclusions and recommendations

The treatment of biomass as zero-carbon in policy frameworks has led governments to provide significant financial and regulatory support for the use of biomass for power and heat. Since emissions take time to be reabsorbed by forest growth, carbon emissions in the atmosphere will increase for a period of decades or even centuries, depending on the feedstock type. Policymakers in consumer countries will be given a false sense of optimism about the progress being made in decarbonizing their energy supply, while producing countries have no corresponding incentive to reduce future emissions in compensation. Subsidies for biomass energy have been delivered–and seem likely to continue–with essentially no mechanism to discriminate between feedstocks with different carbon payback periods, and therefore no effective means of limiting the impact on the climate.

The type of feedstock used in biomass plants is critical. We conclude that only those categories of feedstock with the lowest carbon payback periods should be eligible for financial and regulatory support. This is consistent with the Paris Agreement’s aim of peaking global emissions ‘as soon as possible,’ and reduces the chance of reaching a climate tipping point.

The current sustainability criteria in the EU and UK that define the categories of biomass feedstock that can be supported and the conditions under which they can be burnt do not take account of the real impacts of different feedstocks on the climate and cannot, accordingly, achieve this aim. They are also defective in other ways. (If adopted, the new proposals published by the European Commission in July 2021 would improve EU sustainability criteria somewhat, but their impact would be very limited.) We therefore recommend that EU and UK sustainability criteria be amended as follows:

Only those categories of feedstock with the lowest carbon payback periods should be eligible for support: sawmill and small forest residues and wastes with no other commercial use whose consumption for energy does not inhibit forest ecosystem health and vitality.

- Much tighter definitions of feedstock categories should be introduced to prevent whole trees being treated in the same way as genuine residues.

- Periodic monitoring of feedstock use and impact should be conducted to ensure that allowable feedstocks are not diverted from other uses–e.g. for wood products.

- Additional criteria should be included to protect particular types of landscape, including primary and highly biodiverse forests, from the extraction of biomass for energy. (This is included in the European Commission’s new proposals.)

- The UK’s adoption of a ceiling on feedstock supply chain emissions of 29 kg CO₂eq/MWh is welcome in limiting the types of feedstock that can be used; it seems likely to restrict feedstocks to domestically sourced products. Similar limits should be introduced in the EU.

- The energy efficiency thresholds for new power stations in the EU criteria should be increased and extended to both older and smaller installations.

- The new proposals from the European Commission to extend support beyond 2026 for the use of forest biomass in electricity-only installations in coal-dependent regions will encourage further coal-to-biomass conversions and should be dropped.

- Feedstock for BECCS plants should be subject to at least the same constraints as other biomass plants.

Emissions from any type of biomass used for energy not satisfying the criteria proposed above should be included in full in the consuming country’s greenhouse gas totals when judging progress against their national targets and in relevant policy frameworks, such as the EU’s Emissions Trading System. Since these categories of feedstock have longer carbon payback periods than those eligible for support under our recommendations, this would be an effective way of ensuring that the period during which carbon concentrations in the atmosphere are higher than they would otherwise have been is not simply ignored, as it is under existing policy frameworks.

Beyond 1.5: Tipping points: Is there a point of no return?

Arctic permafrost and tropical forests are two of the most powerful natural drivers of our climate system, and both are approaching the point of tipping from carbon sinks to carbon sources–with potentially catastrophic consequences. At the same time, the ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica are nearing points of no return, beyond which they may be committed to complete melting that would cause massive sea-level rise. Continuing to emit greenhouse gases without knowing where these tipping points lie is like driving toward a cliff in the fog. This gripping event will explore what we know–and need to know–to avoid going over the cliff.

Watch the video recording.