How much worse will thawing Arctic permafrost make climate change?

Global warming is setting free carbon from life buried long ago in the Arctic’s frozen soils, but its impact on the climate crisis is unclear

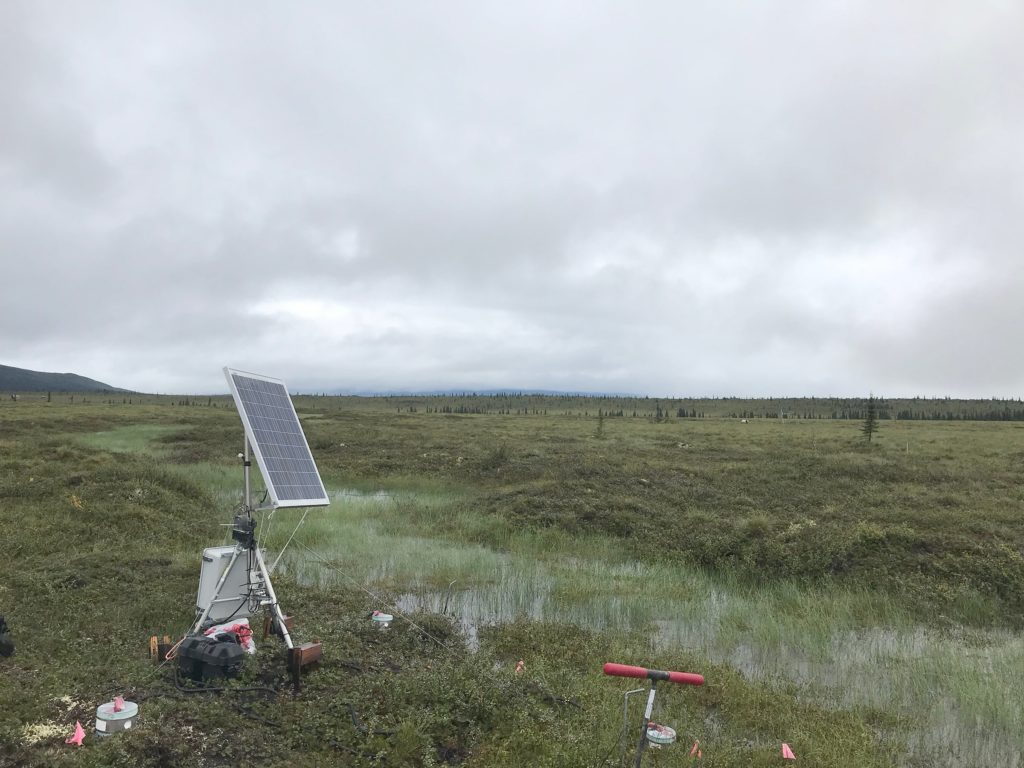

The permanence of frozen ground in the Arctic is no longer guaranteed as Earth’s temperatures continue to climb. But how much the degradation of so-called permafrost will worsen climate change is still unclear, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC’s) Sixth Assessment Report, released this week. The uncertainty leaves researchers with a frustrating hole in their climate projections.

Permafrost covers a quarter of the Northern Hemisphere’s land and stores around 1.5 trillion metric tons of organic carbon, twice as much as Earth’s atmosphere currently holds. Most of this carbon is the remains of ancient life encased in the frozen soil for up to hundreds of thousands of years.

In recent decades, permafrost has thawed because of global warming from heat trapped primarily by carbon dioxide released to the atmosphere from burning fossil fuels. Arctic warming is rising at twice the global average rate since 2000, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. As that increase accelerates the thaw of permafrost, the organic carbon contained within it breaks down and releases carbon dioxide, exacerbating climate change.

Read the full article on Scientific American.

Takeaways from the latest IPCC report

AR6 is a resounding affirmation of what has become increasingly clear not only with each new study but through everyday experience.

Today, the IPCC released the first volume of its latest climate science assessment report (AR6). It is a resounding affirmation of what has become increasingly clear not only with each new study but through everyday experience: our efforts to date have not been nearly enough to alter the disastrous trajectory that rising greenhouse gas emissions have put us on–one of rapid warming, worsening ecological disruption, and increasingly frequent and severe extreme weather events that threaten the health, safety, and well-being of people around the globe.

These reports present no new research. Rather, they are massive syntheses of the ever-growing body of climate science. And, thus, their findings should come as no surprise. Even so, they are important indicators of where we are in understanding and addressing the climate crisis, and there are four aspects of this report that are particularly salient to our work at Woodwell Climate Research Center:

- In a departure from previous IPCC reports, this one notes the importance of considering the full range of climate risks, “including low-likelihood, high impact outcomes,” in decision-making. This, of course, is fully in line with the work of Woodwell’s Risk Program, whether assessing risks to the global economy or helping under-resourced communities plan for greater resiliency.

- Greenhouse gas emissions from permafrost thaw, are not fully taken into account in this report, but at least the issue is explicitly acknowledged. This also represents an improvement over previous IPCC reports, which were based upon models which omitted entirely this potentially important source of emissions. Understanding these emissions and including them in models, carbon budgets, and climate policy discussions generally is an important focus of Woodwell’s Arctic Program.

- All of the scenarios considered in this report show global warming exceeding 1.5ºC by roughly 2030 and highlight the importance of large-scale removal of CO2 from the atmosphere for keeping that exceedance minimal and temporary. Woodwell’s work on natural climate solutions focuses on the best means we have at present for achieving the needed level of CO2 removal.

- However, the report notes with high confidence that land and ocean ecosystems’ are expected to become less effective at absorbing emissions at higher levels of CO2. Our own work has pointed in this sobering direction, which makes it even more important to prioritize forest protection now over reforestation at some future date.

The good news is that as science illuminates the problem, it also points to solutions. And today, as we also observe the UN’s International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, it is appropriate that we recognize the important role that Indigenous communities around the globe play in protecting the forests that protect our climate. Two new analyses involving Woodwell Climate scientists show that Indigenous territories in Brazil experience far less carbon loss from deforestation and forest degradation than other lands, adding to the evidence that strengthening Indigenous land rights is both a just social policy and an effective climate policy.

Of course, this is just one piece of the puzzle. Decision-makers at all levels and across all sectors must take bold action to advance rapid decarbonization, preserve essential ecosystems, and foster resilience in the face of inevitable impacts. At Woodwell Climate Research Center, we’re working with Indigenous leaders and business leaders, local officials and national policymakers, to generate scientific insights that drive the changes our situation demands.

Thank you, as always, for your support and interest in this important work.