Climate policy in the time of Trump

Advancing climate policy in the United States in 2025 requires resolve and focus

2024 DC Fly-in participants head to Capitol for meetings.

photo by Tierney Cross

What keeps Woodwell Climate Director of Government Relations, Laura Uttley going day to day?

Uttley leads the Center’s domestic policy advocacy, and it’s been a hard year for domestic policy. In the past, her work has involved building relationships with members of Congress, tracking climate-relevant legislation, and planning Hill visits and briefings with Center scientists. This year, it’s been all that plus an exhausting gauntlet of crisis response, as climate science falls under attack from an antagonistic presidential administration. It is a federal policy landscape that makes advancing climate research, mitigation policy, and adaptation efforts harder than perhaps at any point in U.S. history.

But waiting for easier times is not an option.

Since the start of the new presidential administration in January, federal funding and support infrastructure for science has been slashed, and many laws, court rulings, and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations that form the foundation of the U.S.’s climate and environmental policy have been targeted or overturned to make way for an agenda that prioritizes fossil fuels. Protecting as much environmental policy as possible has become an urgent priority for Uttley and the rest of the Government Relations team at Woodwell, but despite the chaos and uncertainty, they aren’t flagging.

“What gets me going on a day to day basis, is that I have a job to do,” says Uttley.

Uttley leads Woodwell scientists, board members, and staff to a meeting on Capitol Hill.

photo by Tierney Cross

Holding back the floodwaters

At the beginning of the year, Uttley and the Government Relations team were bracing themselves for the new administration to “flood the zone.” The tactic, which involves mounting as many attempts as possible to repeal legislation, cut funding, and stymie regular governmental proceedings in a short timespan, is designed to overwhelm potential opposition and the media.

“It is done very intentionally,” says Uttley. “To distract. To exhaust. To cloud your judgment on things, and get you too focused on one area, so that you’re unaware or unable or too limited in terms of resources to work in a different space.”

And that’s exactly what newly appointed officials did—from pulling the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement, to proposing the sale of public lands, to firing staff from key agencies like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), to changing regulation around how the EPA implements signature environmental legislation.

You could make the argument that we should be in any number of fights and policy debates.Laura Uttley, Director of Government Relations

The instinct, Uttley says, for individuals and organizations that care about diversity, the environment, or public funding for science, is to react to everything because every attack feels like a devastating loss. But that is exactly what drains motivation and resources the fastest.

“I don’t have the luxury of outrage right now,” says Uttley.

So she and others have had to stay focused on the most significant policy battles, concentrating resources on the areas most aligned with Woodwell Climate’s mission and expertise.

“You could make the argument that we should be in any number of fights and policy debates,” says Uttley. “But if we go too far afield, the impact of our voice changes in those dialogues that are so core to our mission. Staying focused can be really hard to do when everything feels so deeply important.”

Top Priority: The Endangerment Finding

Among the fights the Center’s Government Relations team has engaged in, protecting the infrastructure of American climate policy has been a chief priority. In July, the administration announced its intent to revoke the Endangerment Finding, which underpins the majority of U.S. climate action. This finding from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) affirms that the emission of six greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere— including carbon dioxide and methane— represents a threat to human health and wellbeing, giving the agency authority to regulate them. The decision was based on rigorous science, and was re-affirmed in a 2018 study, led by then-president of Woodwell Climate, Dr. Phil Duffy, who wrote that in the intervening years evidence in support of the finding had only accumulated.

The current administration has attempted to call into question the scientific basis of the finding by releasing a report from the Department of Energy (DOE) that challenges consensus on the damaging impacts of carbon emissions. The suggestion that regulating emissions has caused more harm than the effects of climate change, according to Dave McGlinchey, who served as Woodwell Climate’s Chief of Government Relations between 2016 and 2025, is a blatant dismissal of scientific fact.

Carbon monitoring equipment like this tower helps scientists study trends in emissions.

photo by Jayme Dittmar

“We built an operation here at Woodwell that is very non-partisan, but the idea that the Executive Branch of the U.S. federal government just doesn’t engage with evidence, or moves forward despite clearly contravening evidence, is a real challenge,” says McGlinchey.

It also dismisses the fact that the EPA’s ability to regulate things like tailpipe and power plant emissions has improved air quality for millions of Americans. The finding has made our skies clearer, lungs healthier, and contributed meaningfully to reducing the U.S.’s emissions.

Legal challenges to the proposed repeal began to roll in almost immediately after its announcement, and the opportunity for public comment on the rule was extended to September 22. The Woodwell Climate team developed an organizational comment in support of the Finding to throw more scientific weight behind the efforts to keep it in place.

Climate risk spans political divides

While the political landscape around climate mitigation remains contentious, opportunities to advance resilience projects on the local scale remain. Communities across the political spectrum are feeling the acute impacts of climate change and need information to protect themselves.

Community Engagement Specialist, Morris Alexie speaks with Senator Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), on behalf of his home village of Nunapicuaq, which is experiencing climate-caused erosion and flooding.

photo by Tierney Cross

“Risk is a bipartisan issue,” says McGlinchey. “Unfortunately, in this country, we have repeated, catastrophic reminders of what climate change impacts look like, so people are attuned to that. They want to understand risk and they want to understand how to become more resilient.“

Andrew Condia, External Affairs Manager, leads the Center’s primary climate adaptation project, Just Access. The initiative connects climate scientists with communities both in the U.S. and around the world to provide assessments of current and future climate risks at no cost to the communities. With a better understanding of how variables like flooding, drought, heatwaves, and fires will impact their communities in the coming years, leaders in municipal governments have been able to have climate-informed conversations about planning, infrastructure, and public health. Even in overwhelmingly conservative areas.

“We work with some Democratic mayors, some Republican mayors, and they are lined up and equally as engaged in the process,” says Condia. “They understand the importance of this information and know that it’s a critical tool to help them as their communities grow and change in the future.”

Andrew Condia examines infrastructure during a Just Access scoping meeting in Louisville, KY.

photo courtesy of Andrew Condia

The sweeping nature of cutbacks on the federal level has meant that municipalities are now one of the only places these conversations are able to move forward.

“I think local governments recognize that in the absence of federal leadership, it’s up to them to step up to make progress on these issues. It’s the only climate action in the country that is really making meaningful progress right now,” says Condia.

Bigger picture, longer term

At higher levels of government, McGlinchey says the current top priority is to maintain relationships with policymakers and lay the groundwork for long-term changes while momentum in the short term has been halted.

“We can’t look at how bleak the landscape appears to be and throw our hands up and give up. Because political winds shift frequently in this country, and fairly dramatically, and when they shift again, we don’t want to start at zero,” says McGlinchey.

For the past three years the Government Relations team has organized “fly-ins”, which bring Woodwell Climate scientists to Washington D.C. for meetings with Members of Congress and their staff. The fly-ins are key to how the Center stewards relationships on Capitol Hill and raises issues like permafrost thaw or flood insurance risk to the attention of legislators. Despite this year’s political changes, Uttley was still able to bring 12 scientists, board members, and staff for meetings with 15 congressional offices this September.

The Woodwell Climate 2025 Fly-In team.

photo by Eric Lee

Woodwell has also remained active in coalition groups, which combine the power of many organizations to push for common goals.

“We’re engaged in the Adaptation Working Group, Friends of NOAA, the Coalition for National Science Funding, and more,” says Uttley. “From a policy perspective we have really seen the advocacy community rally together this year.”

And while the U.S. regresses on climate action, the rest of the world continues forward. Woodwell Climate is helping to propel important climate policy on the international stage, forming a delegation to the annual UN Conference of Parties (COP) in Belém, Brazil in November. Given its location, tropical forests will feature heavily on the agenda this year, and the Center will be showcasing emerging work on tropical regenerative agriculture, sustainable development in the DRC, and financing for forest protection. The Center is also collaborating with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to provide technical support for countries submitting biennial transparency reports on their progress towards climate goals.

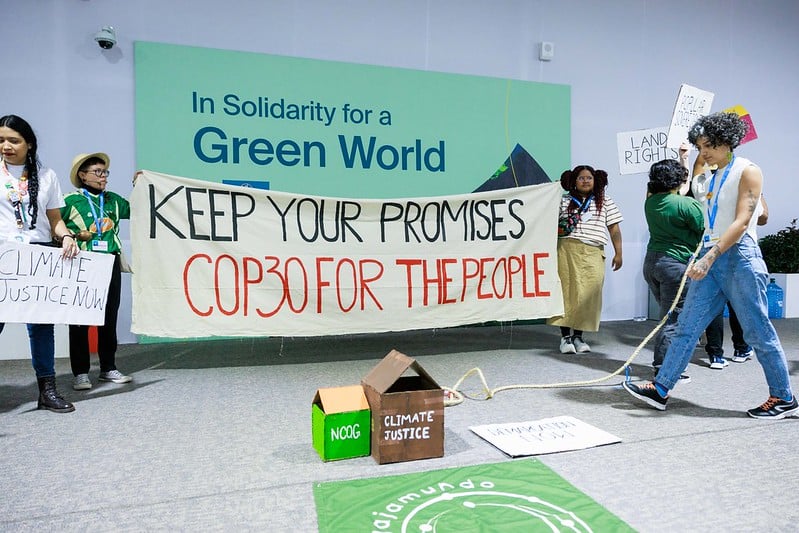

Activists at COP29 in Azerbaijan in 2024 advocate for action at COP30, to be held in Brazil in November 2025

photo courtesy of UN Climate Change/ Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Momentum on climate means telling climate stories

Still, facing down the urgency and magnitude of climate change, these incremental wins and slowly unfolding plans often don’t feel like enough compared to swift federal actions. Especially for individuals who don’t have their hands on the levers of power. But Uttley says the local level is where most change has always started, and individuals can make a difference.

“While I’m working to make systemic change on the federal level, one of the most powerful things each of us can do to keep up momentum on climate is to tell stories about local impacts,” says Uttley. Whether it’s about soccer practices canceled for heat or commuting lanes flooded, stories that connect climate change to our daily lives help change minds and motivate action.

Working on climate policy in times like these is a careful balance of hope and disappointment, Uttley says, but in order to move forward hope always has to win out. Not wishful thinking, but the kind of hope that springs from facing down the obstacles and getting to work.

“I’ve been in public policy and advocacy for 15 years,” says Uttley. “If I didn’t have a strong sense of optimism and hope, I would not be able to do this job.”