Natural climate solutions are identified and designed with full consideration of risks from climate extremes, natural disturbances, and socioeconomic events.

Prepared by Zach Zobel and Dave McGlinchey

Summary

The carbon stored in high-carbon ecosystems may take decades to centuries to replace if the stocks are lost. Avoiding the fragmentation or degradation of these ecosystems can result in an immediate reduction in emissions and can help protect biodiversity. When possible, restore degraded land to native vegetation and biodiversity while increasing carbon stocks to levels consistent with the potential of the site.

Description and rationale

The impacts of climate change are already being felt and will only worsen, with direct ramifications for natural systems throughout the United States. These impacts will then affect—to a greater or lesser degree—the ability of those natural systems—forests, grasslands, wetlands, and soils—to store carbon and mitigate climate change.

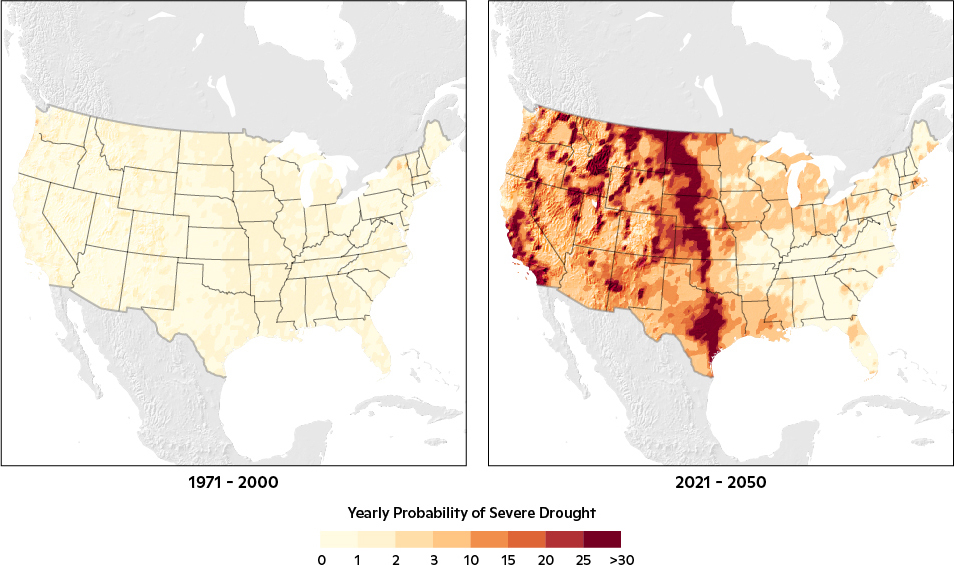

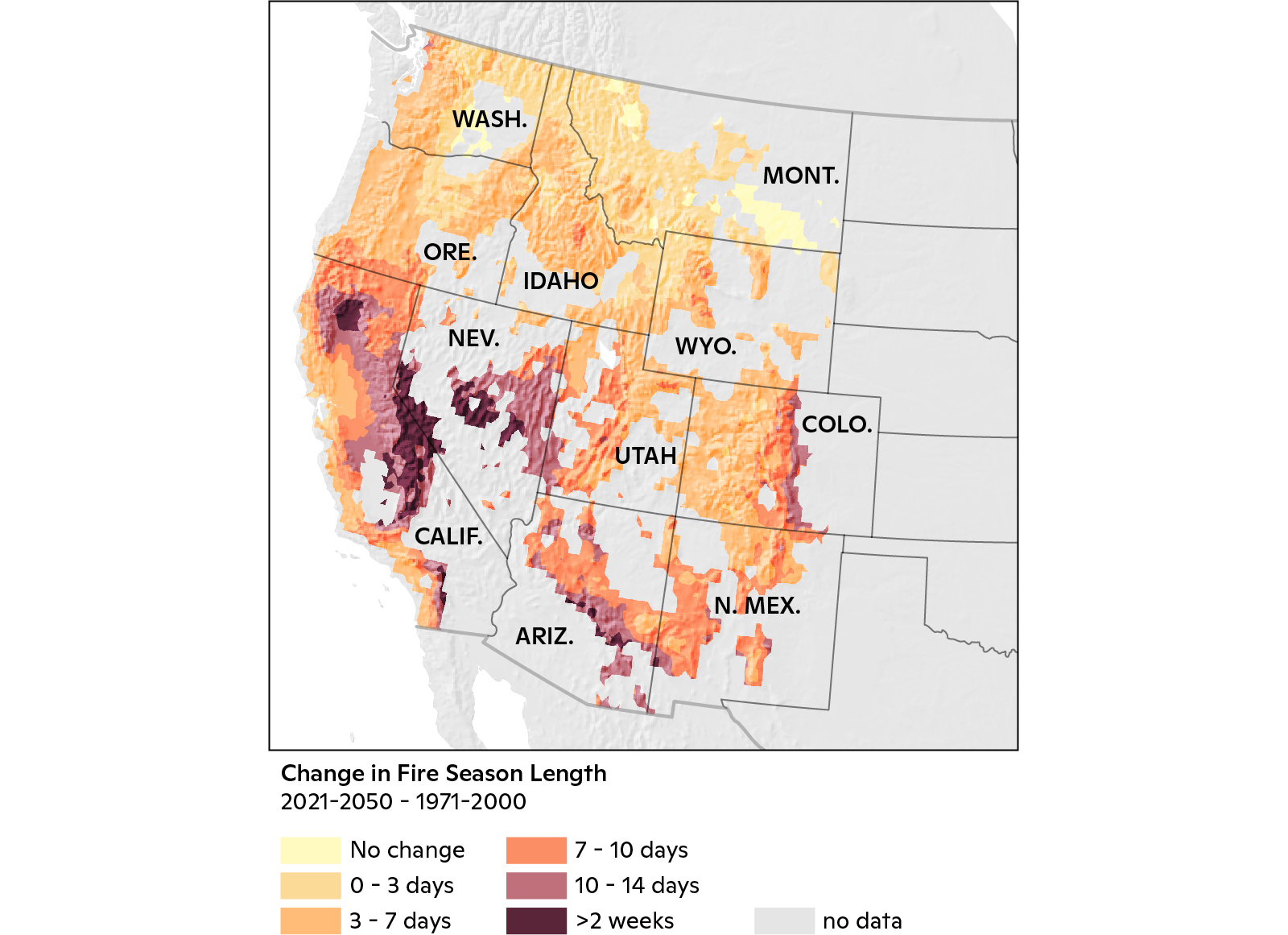

While developing NCS policies, risks should be considered for the range of potential climate change perils: drought, precipitation extremes, flooding, hurricanes, heat stress, invasive species, and wildfire. These hazards were identified as the prevalent risks in the United States out to mid-century—a timeframe that is relevant for both mitigation efforts and near-term policymaking. This information should be understood and internalized by policymakers to avoid implementing or investing in NCS that will not remain viable long-term, though some activities like reducing deforestation and forest degradation could help guard against future hazards. For example, climate risk modeling could help identify areas that will become more prone to drought—and thus, unsuitable for certain NCS—in coming decades.

Changing climate conditions will also shift ecological zones. For example, climate change is projected to alter the distribution of tree species as a result of environmental changes that will affect growth, mortality, reproduction, disturbances, and biotic interactions (Rogers et al. 2017). A region that currently sustains certain tree species could become inhospitable, or overrun by invasive species that outcompete native species, or could become warm enough for migrating pests. These projected changes will affect the net greenhouse gas balance of ecosystems in the future and could result in less net emissions reductions from a given NCS than expected.

How the principle may be applied to specific climate risks—drought and wildfire

1. Drought

Since the 1980s, droughts have been the second-most costly weather/climate disaster in the United States, generating an average $9.4 billion loss per event (NCEI NOAA). California and much of the western United States are arid regions, historically prone to drought (Bolinger 2019). The 2012–2016 California drought, driven primarily by record high temperatures and less than normal precipitation, was by some measures the state’s most extreme drought of the past century with the 2014 peak being the driest period over the last 1,200 years (Griffin & Anchukitis 2014). The drought caused a widespread mortality event of 48.9% of the state’s trees across 102 million acres of forests in 2014-2017 in the central and southern Sierra Nevadas, which may lead to forest type conversion or even a long-term shift to grassland (Fettig et al. 2019).

In the future, drought frequency and severity is expected to worsen as global temperatures increase and precipitation becomes more variable (Cook et al. 2015; Huang et al. 2017). By 2021-2050, the probability of extended severe drought increases to at least 3 times more likely (>3%) across most locations of western and central U.S, with severe drought becoming more than 20 times more likely in many locations (darker reds in Figure 1). Such widespread drought in these regions would affect all ecosystems, including those essential to sustain food supplies, and could severely impact NCS designed to reduce net GHG emissions by enhancing carbon sequestration in forests and soils.