Follow an Arctic scientist into the changing tundra

Research Assistant Kaj Lynöe marks a decade of Arctic research with a marathon field season. Here’s what he experienced.

Kaj Lynöe hikes up Tsina Glacier in Alaska.

photo courtesy of Kaj Lynöe

2025 marked the first year I went out in the field as a member of Woodwell Climate’s Permafrost Pathways monitoring team. I travelled around Alaska to our carbon monitoring sites, maintaining and installing equipment and taking static measurements of greenhouse gases—namely carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide—in various degraded and disturbed permafrost landscapes around Fairbanks and west of Prudhoe Bay by the Arctic Ocean.

In late April this year, I returned to Toolik together with Dr. Jennifer Watts, Dr. Kyle Arndt, Christina Minions, Dr. Kelly Gleason (snow scientist from Portland State University) and photographer Jayme Dittmar to install an eddy covariance tower by a retrogressive thaw slump. Eddy covariance towers monitor and capture fluxes, or the exchange between land and atmosphere, of energy and greenhouse gases. Thaw slumps are areas of tundra that have collapsed due to thawing ice-rich permafrost. When the ice melts, the ground collapses, revealing old, buried carbon rich soils that begin releasing their carbon back to the atmosphere. The towers help us better understand how much carbon these features contribute to calibrate models of Arctic carbon emissions.

map by Christina Shintani

Spring is one of the best times to be in northern latitudes. Near endless days, the bright snow, the monochromatic stretches of landscapes, the binary experience of both intensity and complete stillness. Now suddenly, the interruption of a small group of people gathering, pulling around equipment, cords, cables, instruments, and then suddenly there is a new structure in the landscape and the people disappear. Off to a great start, we packed and organized our tools and equipment and headed from the wintery landscape of the north towards the onset of green-up to the south.

Kaj Lynöe takes a coffee break on the tundra near Toolik.

photo by Christina Minions

Back in Fairbanks, the bloom of birches in early June is one of my favorite sights. The dense stretches of light, delicate greenness and resinous fragrance from the new sprung leaves that are drowning in summer sunlight makes me almost feel all the carbon dioxide being sucked out of the air by the trees. This, again, makes me really appreciate the northern latitudes. The vastness that cradles your existence grounds you and at the same time lifts you with the intensity of the surrounding life. It is an energy that can only be felt at these latitudes. A form of mania that propels you onward without pause.

In late June the trip headed to Nome and Council where I, together with colleagues Dani Trangmoe and Dr. Kelcy Kent, maintain the tower there. With each site visit, not only do I get an improved grasp of the equipment, but also a better understanding of the surrounding landscapes, now even more chlorophyll-saturated peak green. I shuttled to Anchorage and then back up to Bethel with Trangmoe to join Dr. Jackie Hung and Christina Minions at the two towers located a 40-minute flight northeast of the town. Here, we upgraded solar structures, maintained and swapped equipment and hauled out old and damaged power supplies and miscellaneous materials. I really appreciated the time being out there and the sense of community that comes with remote camps, although we only stayed out for about a week.

A form of mania that propels you onward without pause.

Afterwards we circled through Anchorage again on our way to the very top—the Arctic Ocean. I assisted Hung and fellow researchers from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute and the Marine Biological Laboratory to collect greenhouse gas measurements from coastal tundra. The contrast of the flora and fauna against the infrastructures from the oil and gas fields makes for a surreal sight. From here I am going southward again, stopping at Toolik to check on the new tower and enjoy the buzzing environment that Toolik is offering during this time of year. The intensity of the arctic summers is reflected in the frantic work of scientists that all gather here to conduct a wide range of work.

At what other place in the world than Toolik would one be able to hike out on the tundra and do maintenance work on an eddy covariance tower in the morning, come back for a snack, go out in a helicopter to search for new areas of permafrost degradation, get a panoramic sight of thousands of caribou, come back to a hearty meal, and finish off the day catching some grayling at the river inlet by the Toolik lake. The beautiful clear light, the humming of mosquitoes, and the rippling sounds of the water give me a sense of belonging, a sense of home.

Thaw slump near Toolik Field station.

photo by Kaj Lynöe

I spent my last weeks in Alaska in Fairbanks again, making boreholes in permafrost together with a magnificent team gathered from across the U.S. We can learn a lot from these seven-meter-deep boreholes. Not only studying the samples that we retrieve, but also how these permafrost soils evolve and change with climate change with sensors that monitor variables such as temperature, oxygen and soil moisture. The drilling was challenging and physically demanding, but at the same time something of a treasure hunt as each of the soil samples we were able to retrieve has the potential to unlock a wealth of information that can help us expand our understanding of the changing permafrost soils in the region. In the end it felt well worth the effort, especially being privileged to work with such a dedicated and knowledgeable group.

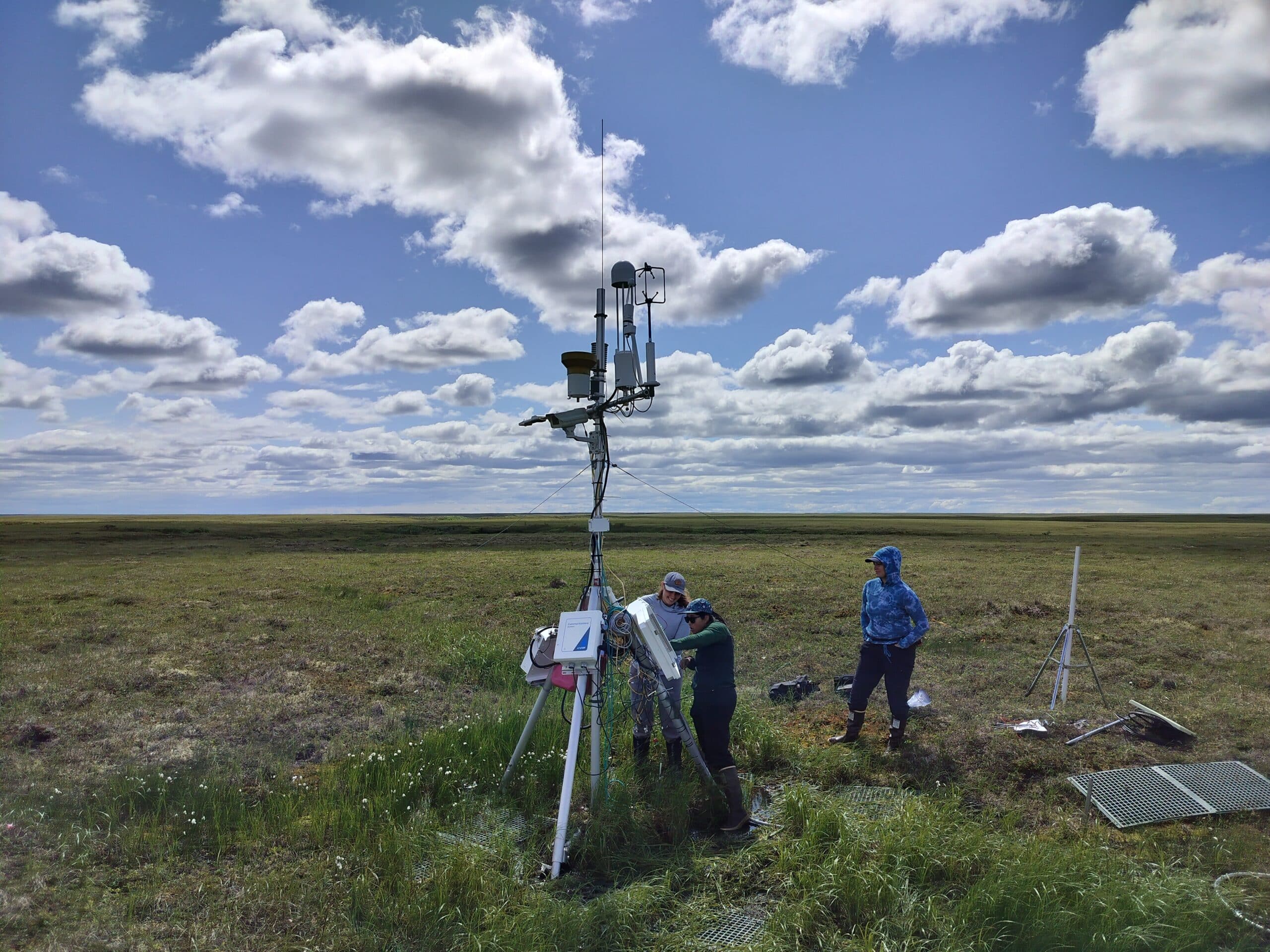

2025 also marked my tenth year of working in the Arctic. As a junior scientist, I remember reading and hearing about Woodwell Climate’s work in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta long before I joined the team. I remember spending a full summer on the Delta by the coast, learning about and experiencing firsthand the effects of both permafrost thaw and coastal erosion. Knowing that Woodwell’s first eddy covariance tower was installed in this region around the same time, and that it has been collecting data ever since, has given me a sense of perspective not only on my career, or the Permafrost Pathways project for which this tower was the springboard, but also the future of the Arctic landscapes that I have come to love.

Woodwell researchers troubleshoot glitches on the eddy covariance tower on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta.

photo by Kaj Lynöe

I am grateful to have been given this perspective, and to work in and celebrate all these unique and beautiful places. If it wasn’t for the people and the relationships built through this work, we would know much less about these complex and fascinating landscapes. It is through these encounters with people and the environment that we can not only deepen our understanding but also gain connection. These encounters and interactions give a sense of belonging as a part of something bigger.