This is what climate resilience looks like

Climate change is here. Resilience is how we will adapt to, grow from, and ultimately overcome it.

Rampart, AK

photo by Keri Oberly

Climate change is a massive problem, with far-reaching effects that touch every aspect of society. It’s also already here. The impacts long forecast by scientists—heat waves, droughts, encroaching sea levels, thawing Arctic ground, frequent storms, and wildfires—are being felt now by communities from Alaska to the Amazon. But these communities, throughout the hardships being thrown their way, are learning to adapt. While national and international climate efforts take small steps, towns and cities are striding forward, building resilience through community engagement, urban planning, and advocacy.

What resilience looks like is different in every community. It is defined by each place’s unique challenges and ways of life. It requires creativity, trial and error, and unwavering persistence. These five community leaders share lessons learned from lives spent anticipating oncoming obstacles, finding and inventing solutions to each new challenge, and cultivating resilience in the face of climate change.

Resilience is… Proactive planning and learning from others.

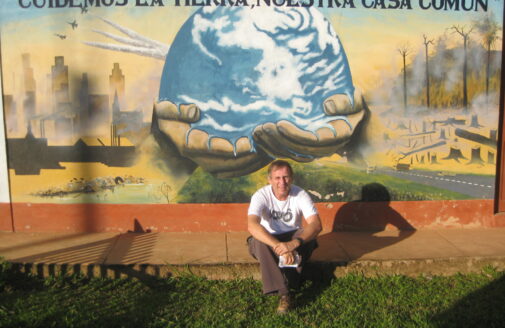

Dale Morris

design by Julianne Waite

Dale Morris

Former Chief Resilience Officer for the City of Charleston, SC and Climate Adaptation Consultant.

Charleston is a coastal city that floods on average 70 days in the year. When Woodwell Climate reached out to offer a free climate risk analysis as part of the Just Access project, Charleston was in the midst of their own comprehensive water plan. Morris recognized the need for expanded risk modeling for the wider County of Charleston, which encompasses three of the four largest cities in South Carolina, and whose upstream flooding risks were less understood but already impacting downstream communities. He facilitated the project, which modeled flood risks out to 2080.

“In the City of Charleston we weren’t at all surprised, but when we shared the results with the other cities, everyone was like ‘whoa, this is worse than we thought.’ Floodplain inundation from rainfall was a big part of it. And when you factor in sea level rise at the outfall of creeks and rivers, there’s less drainage capacity. Where does the water go?”

For Morris, understanding risk is a crucial first step towards building a resilient community. The next is putting that knowledge to use. In Charleston, city and county officials have used the Woodwell report to apply for grant funding to further improve stormwater management.

Though the risks can sometimes seem daunting, Morris says learnings from other communities, even those many thousands of miles away, can offer inspiration and guidance. Earlier in his career, Morris managed outreach for the Dutch government in the United States, helping apply learnings from the Netherlands to community flood programs.

“The Dutch, by necessity, have to know how to live well with water, with the use of different approaches—hard engineering, soft engineering, good spatial planning.”

Morris was at the Dutch Embassy when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005. Seeing the devastation there affirmed his belief that planning and governance also play a huge role in how well a community can recover from a disaster.

“I saw very clearly this was a failure of government and governance at all levels. The economic disruption, the family disruption, the devastation across wide swaths of New Orleans and along the Mississippi coast, it made me mad, and it motivated me to do more.”

“More” means more planning, more foresight, tackling future risks before they happen, and pursuing projects that produce multiple benefits.

“These are generational kinds of recoveries. We should think about proactive investments, not reactive responses.”

A resilient Charleston looks like: Clear future flood risk assessments, adaptive management plans for residents in flood zones, smart new development that can receive moving residents, city infrastructure planning that adapts to changing future conditions

Resilience is….Changing mindsets and changing economies.

Ben Robinson

design by Julianne Waite

Ben Robinson

Martha’s Vineyard Commission member and founder of the MVC Climate Action Task Force.

The island of Martha’s Vineyard can be a place of strong contradictions. Transient vacation-goers share the beaches with life-long residents. Multimillion dollar homes are being constructed while local workers struggle to find affordable housing. Rural fields border suburban neighborhoods which, in turn, border both forests and salt marshes.

These complex dynamics are what Robinson grapples with as he leads the Island’s climate adaptation planning efforts. As a member of the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, he aided the creation of a climate action plan to identify areas of work across sectors, from food security to transportation. Woodwell Climate worked with the Commission to produce an assessment of the Vineyard’s drought, precipitation, and wildfire risks, as well as a study of existing carbon stores on the Island.

According to Robinson, the Vineyard faces not only increasing climate risks but also challenges in creating the needed social changes for adaptation.

“The social change piece is the one that’s really been the most frustrating, because it entails sacrifice. It entails recognizing the privileges that we’ve had and we still have and taking on a global responsibility.”

One of the trickiest areas to tackle has been the Island’s main economic driver: tourism. Summer months are extremely popular with wealthy tourists, and much of the Island’s infrastructure is built to serve this influx of temporary residents.

“The Vineyard is really catering more and more every year to a wealthier and wealthier constituency. And they demand more services, more things, a different feel. And that level of over-consumption is one of the primary drivers of climate change.”

It has also made life harder for ordinary residents, driving up property values to an untenable degree, forcing much of the labor force to live off-island and commute.

“Those are really poor trends for a community that wants to be resilient.”

Additionally, reliance on imports undermines food security for residents. Currently, close to 95% of food has to be imported from the mainland.

“Right now there’s no way we would survive without the supply chain to the Island, which has just become more and more intertwined with our everyday lives.”

The Vineyard is working to improve its food security by producing more on-island through agriculture and foraging. And despite the challenges in other areas, Robinson reminds himself that the best thing he can do is just keep chipping away at the problem.

“It’s easy to be frustrated in this kind of work, but this is a multi-generational change. I’m only going to see one period of it, and then somebody else is going to pick it up. This is just going to be a slow process of evolving our community. If we can do it right, we’ll be better off in the future.”

A resilient Martha’s Vineyard looks like: A robust, electrified public transit system, a diversified economy with a non-extractive tourism industry, locally produced food, offshore wind

Resilience is…A holistic approach to conservation.

Alexis Bonogofsky

design by Julianne Waite

Alexis Bonogofsky

Director of the Sustainable Ranching Initiative for World Wildlife Fund and Yellowstone County Planning Board member.

Being a rancher on the Northern Great Plains can be challenging. Profit margins can be low. Markets can be uncertain. And then there’s the increasing droughts and unpredictability of precipitation caused by climate change. As a resident of Billings, Montana who runs her own family sheep and goat ranch, Bonogofsky is acutely aware of these challenges.

“The larger Northern Great Plains is definitely experiencing impacts from climate change already. Our winters are getting warmer, so we have less snow pack, and we have less water going into the growing season and into the summer.”

Bonogofsky works on programs at World Wildlife Fund (WWF) that provide funding support and guidance for ranchers pursuing regenerative grazing practices which can make ranches more resilient to climate change. Woodwell Climate partners with WWF to analyze ecological data that can help inform those practices and model future outcomes based on changes in land management. When properly managed, grazing animals can actually help mitigate climate change as well, promoting the growth of native plant species that lock away carbon in their deep roots.

“When you think about iconic Western wildlife, grassland ecosystems are where they thrive and where their best habitat is. Ranchers are managing a lot of grass, and the healthier the grasslands are, the more wildlife we have and the cleaner water we have. Grasslands also sequester a lot of carbon, so healthy grasslands that stay intact are necessary to help mitigate the effects of climate change.”

To improve management practices and achieve healthy grasslands, Bonogofsky says, you have to employ solutions that address the entire system holistically— and that includes the people.

“For resilient communities and ecosystems, you can’t separate the people from the land. For the land and wildlife to be healthy, the people in those communities have to be healthy too.”

That means conservation work isn’t always just protecting plants or animals. It’s also working with community groups to improve housing options in nearby towns or setting up daycare services for ranching families. Strengthening communities, Bonogofsky says, makes people more likely to stay and invest in a place, to do their part in making it better.

“I do this work because it matters. I have a niece and nephew and I want to say to them that I did everything I could to try to make the place better—a place where people can thrive in the future. I’m surrounded by people every day that are making a difference in their communities. And I think if we all do that where we’re from, we actually have an impact.”

Resilient rangeland communities look like: Diverse and intact native grasslands, ranches that are profitable while storing carbon and maintaining ecosystem services, rural communities with services like daycare, housing, and healthcare

Resilience is… Getting creative with your resources.

Sean Hogan

design by Julianne Waite

Sean Hogan

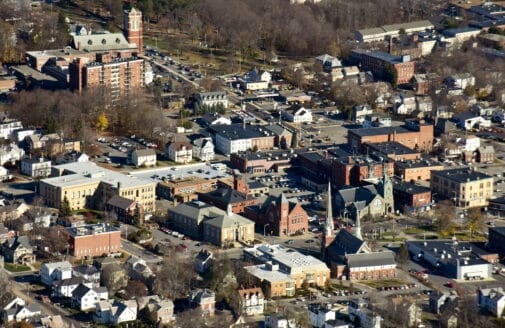

Environmental Sustainability Manager for Barnstable, MA

Hogan’s job is to care about everything climate change, energy, and emissions-related in the town of Barnstable, Massachusetts. He works with the municipal government to identify and pursue funding for projects that could help the town adapt. Barnstable, the largest town on Cape Cod, is one of several Massachusetts communities for which Woodwell Climate conducted a risk assessment, modeling flood risk and stormwater system vulnerability.

Because of his position, Hogan has a clear view into the challenges faced by municipalities in regards to climate resilience. Funding is often short, offices understaffed, and public opinion hard to sway. Hogan has found the best way through is to chase opportunities that combine immediate positive impacts with long-term climate benefits.

“So far, I’ve found in municipal work you have to work opportunistically as to where grants might be available or where there’s institutional interest. We have a finite amount of resources, and if we can husband those resources appropriately, we can spend them in ways that serve the public good.”

Hogan uses the example of electric vehicles, which reduce emissions from transportation, contributing to long-term climate mitigation as well as reducing air pollution for residents in the near term.

“[Climate change is] a problem that’s uniquely designed to foil humans, because we have a hard time grasping those kinds of slow-moving crises. So you either have to change people’s minds, or you find projects that fit into a more favorable psychology.”

Funding opportunities for adaptation projects of all kinds have also become more uncertain with a federal administration slashing climate programs.

“We’re having to come to terms with the change in administration and the financing landscape. We’re gonna have to navigate this period by being a little bit cautious and we’re going to have to become more creative and keep a closer eye on the bottom line so we can create the savings necessary to fund more.”

Resilience will also involve building positive relationships, which for Hogan have been crucial to moving work forward.

“Relationships are important for everything— for building political support, access to resources, expertise, and different perspectives.”

A resilient Barnstable looks like: Electrified systems that don’t depend on fossil fuels, loan programs to help homeowners install solar and resources for renters looking to lower energy bills, public projects that offer both immediate and long-term benefits, dedicated staff time to pursue climate and sustainability solutions.

Resilience is… An uphill battle with a wildfire behind you.

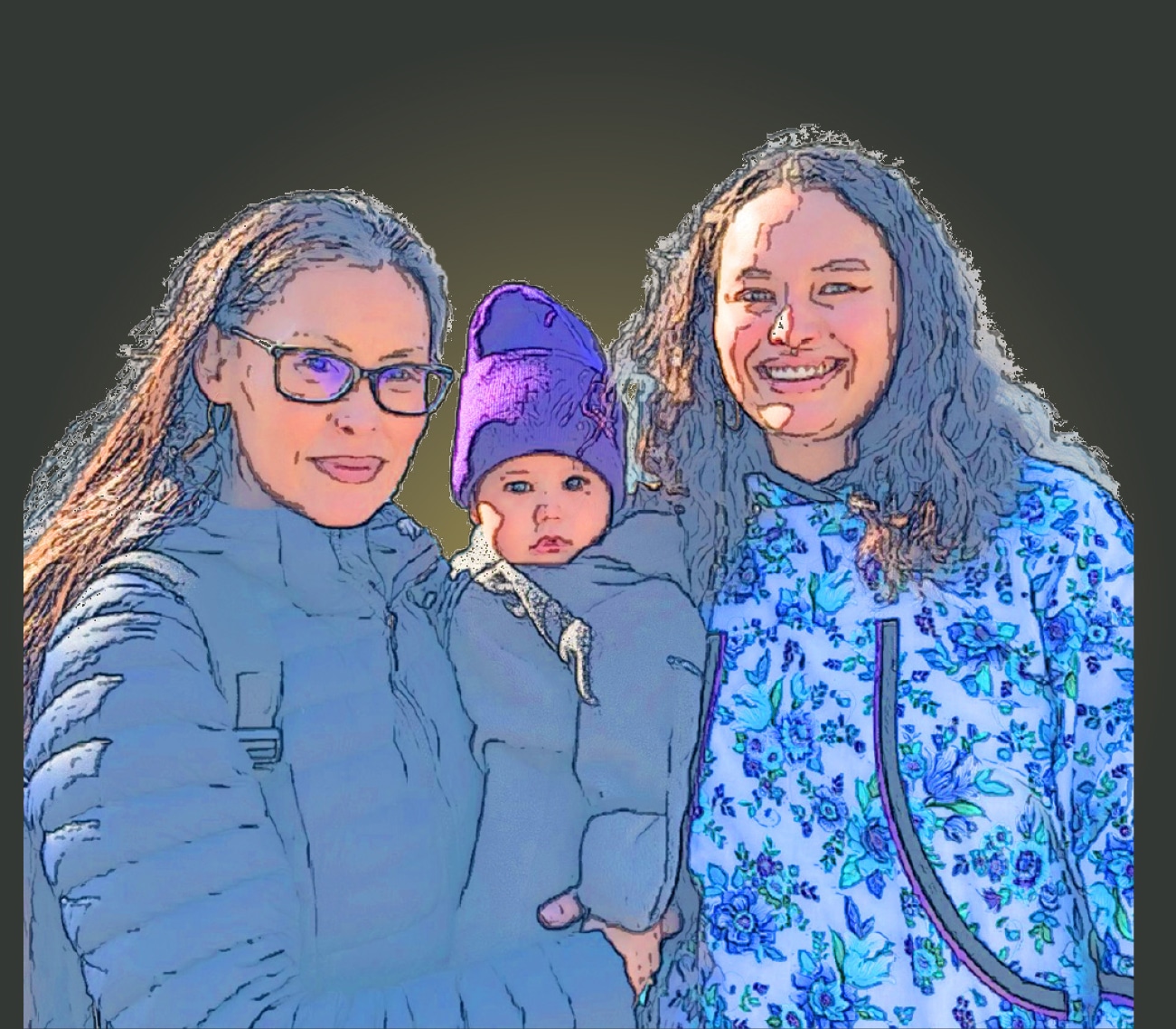

Brooke Woods (left) with her youngest and oldest children.

design by Julianne Waite

Brooke Woods

Climate Adaptation Specialist for Permafrost Pathways and Tribal Citizen of Rampart, AK.

Woods’ hometown of Rampart, Alaska is a small fishing village on the Yukon River. Here, Alaska Native residents practice a subsistence lifestyle of hunting, fishing, and living off the land. Rampart, like many communities in interior Alaska—and across the Arctic—is feeling the impacts of the warming climate now.

The Arctic is one of the fastest warming places on the planet, and as it heats up, permafrost, or perennially frozen ground, upon which many villages are built, is thawing. This can lead to erosion, ground collapse, and infrastructural damage. Woods’s role on Woodwell Climate’s Permafrost Pathways project is to use her policy expertise to help Tribal partners navigate the tricky landscape of federal and state agencies and funding, as well as uplift tribal sovereignty.

On the Yukon River, one of the biggest concerns is the complete collapse of multiple salmon species. Salmon are suffering heat stress from increased water temperatures, changes in the marine environment, overharvest from bycatch in federal and state fisheries, and competition from hatchery-produced fish.

“We have not been able to fish for five years with an expectation that we will not fish for seven more, and that is a climate and cultural crisis.”

Losing access to these fish cuts off Tribes from a traditional cultural practice as well as a critical food source. Both state and federal agencies are involved in managing fisheries in Alaska, and while there are options for consultation, there is no deference to Tribes in decision making.

Additionally, the threat of permafrost thaw places Tribes in an emotionally challenging position. Community members must decide whether to relocate their villages or stay and shore up crumbling infrastructure, with little guidance or support from government agencies.

“There is no adaptation framework for the crisis tribes are in when it comes to relocation. One big hope of this project and working with our Tribal liaisons is developing that [framework] in any stage. That would be a big success.”

The fight for deference, respect, and resources has not been an easy one. Woods compares it to escaping a wildfire to face an uphill climb. But her people’s history of resilience—of maintaining their connection to the land over 10,000 years in Alaska—gives her strength.

“You get out of the wildfire and you make your way up, and it’s a constant fight. Our ways of life are so connected to our ability to hunt, fish, and gather that Tribes are willing to continue this good fight. When it comes to advocating for our ways of life, our people are so humble and working tirelessly.”

A resilient Yukon River community looks like: Healthy salmon populations, stable permafrost, legal deference to Tribes in decisionmaking around natural resources, federal and state support for relocation, continued traditional ways of life